Estimated Read Time: 16 minutes

Does Nature Need Half?

This class isn’t just theory; it’s not abstract.

This class is the foundation for understanding real issues in the real world – issues that affect you and me, today and tomorrow.

How so?

Well, for starters, it’s the first step towards understanding what it will take to truly balance the needs of people and nature.

Does that matter?

Well, this challenge is as pressing as it is interwoven with other issues we face – problems like economic insecurity, social justice and democratic health.

By finding a better balance between people and nature, we can create a ripple effect of understanding and possibility to tackle other, at times, more divisive issues in our society.

Maybe you think: This isn’t a hard challenge – the solutions are obvious.

Yet nothing is as easy as we assume it should be, in part because even when we think problems are black and white – good versus evil – they rarely are. Almost every issue is maddeningly complex, made all the more difficult when emotions like uncertainty, anger, hopelessness and fear are added to the mix.

And about now, you might think, well, none of this is actually my problem. And it probably shouldn’t be. But it is.

You see, not only are decisions being made today that will directly affect your future, right now, you are also entering your years of peak creativity.

As Ilona Dougherty argues, “young people from 15 to 25 are at the height of their lifetime ability to be creative, to be innovative. All these incredible abilities peak during that time of life, and they have the full intellectual capacity of adults. We underestimate young people all the time and we need to stop doing it.”

Ilona knows better than most. She co-founded Apathy is Boring as a student and is the co-creator of the Youth & Innovation Project at the University of Waterloo. Her ground-breaking research has proven that your ideas, with help and refinement, are the very ideas that can help us create that better balance – that better tomorrow.

Ilona knows better than most. She co-founded Apathy is Boring as a student and is the co-creator of the Youth & Innovation Project at the University of Waterloo. Her ground-breaking research has proven that your ideas, with help and refinement, are the very ideas that can help us create that better balance – that better tomorrow.

“The research is very clear,” Ilona says. “For young people to grow up to be healthy, engaged adults, it’s all about having a sense of purpose and having an opportunity to make impact.”

In other words, you might feel that you’re just one student, without the power or influence to determine how late you can stay out on the weekend, let alone solve the world’s problems, but the reality is quite different.

As Ilona explains, “The only way to be a change maker is to be a change maker while you’re young.”

That’s right: You’re powerful because of your age. You can solve any problem we face because of your creativity.

“Young people have unique abilities while they’re young that society needs.”

Exactly, Ilona. And we all need your creativity. Right, Dr. Aleem Bharwani?

“Our most influential and impactful ideas will come from young people today who are growing up in this world.”

Adults – leaders – are so immersed in the problems we face they often can’t see the forest for the trees.

We need you to take a new look at old, if worsening, problems to see if there is something everyone else has missed. We need you to understand how hard truths collide and find ways to do better by different peoples and different communities – do better for more people and for nature.

Because we can all agree that we need to do better.

Discuss

Good points, but let’s get really specific.

Scientists have analyzed Earth’s record-keeping system – fossils – to understand how often natural selection creates natural die-out – what’s known as the Background Extinction Rate. And though no one is certain – fossil records aren’t quite the Wayback Machine – most believe one species goes extinct per Million Species Years.

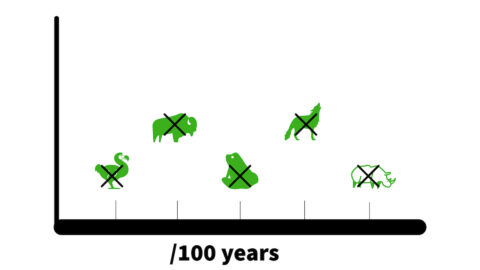

Our current extinction rate, depending on what mathematical equation you believe and use, is ten-to-10,000 times higher than the planet’s Extinction Background Rate – the ‘natural’ natural selection, if you will.

Which is a big spread, but consider this:

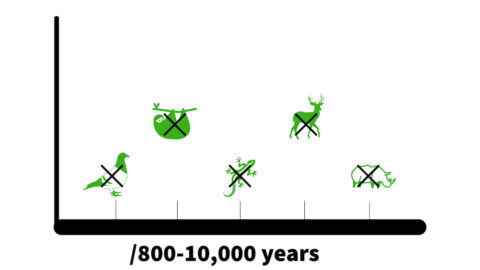

Of the species that have been known to exist and disappeared during the last century, their loss should have taken 800-to-10,000 years to occur. Not the 100 years it actually took.

And that’s according to a study that used a “conservative background rate of two extinctions per million species-years.”

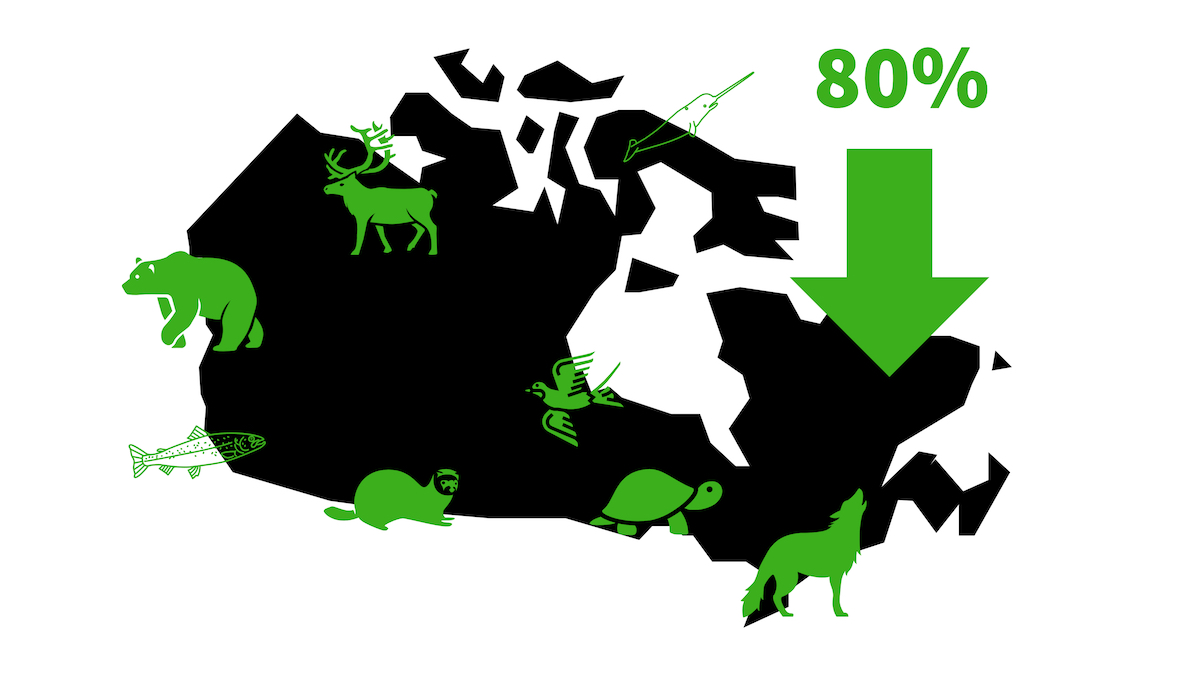

Globally, nearly 70% of every monitored species is either decreasing in population or range, or both.

In Canada, a recent, comprehensive report that combines data from every level of government suggests that of the 50,500+ species we monitor, 1 in 5 are facing at least some risk of being lost and for 2,000 of those species, they’re at high risk of disappearing from Canada’s landscape.

Those are big, worrying numbers – and the problem is increasing. Fast.

How fast?

Well, according to the World Wildlife Fund, the largest environmental organization in the country, their research suggests that the average populations of threatened species in Canada have declined by almost 60% – with some data suggesting that for half of those species in decline, they’ve lost more than 80% of their population numbers in just 50 years. It’s a major reason why more than 500 species are legally listed as being at risk of extinction by the federal government.

For all these reasons, some have concluded that we’re entering a period of mass extinction – a cycle where roughly three quarters of all species disappear in a span of a few million years. There have been five in history – of course, the most famous being the one that whacked the dinosaurs.

If we’re entering a sixth mass extinction, unlike past extinction events, this one is human-caused, scientists tell us. But that is, of course, a debate and, frankly, not a particularly helpful one.

Why?

Because the why distracts from the real issue: Un-natural natural selection at a rate well above the Background Extinction Rate means only one thing: Biodiversity loss.

“The bad news is that in most parts of the world it is declining and it’s declining at all levels.”

David Cooper was the Deputy Executive Secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity – a United Nations body that works to coordinate global efforts to protect biodiversity.

“Life on earth in the broadest sense depends on biodiversity and the ecosystems that biodiversity makes up.”

And it’s not like there’s just one issue driving the global – or national – biodiversity decline.

Habitat loss. Pollution. A changing climate. The exploitation of wildlife. Invasive species. All of these are massive problems, and each issue is connected to the others, making solutions even harder to come by.

As David tells us, “there’s no single answer, so I would say: be wary of simple solutions to these complex problems.”

Indeed, protecting biodiversity will be hard work and will require creativity. But David explains there is good news.

“People are more likely to take actions if they see other people also taking actions.”

And people are taking action. One person, Dr. Harvey Locke, is championing an idea that he hopes will act like an electric paddle to the troubled heart of biodiversity.

“We really need to protect half the world in an interconnected way. That’s really what the numbers are.”

A call to protect half the Earth?! Harvey says it’s a solution our world needs.

“Well actually more than half in the large wild areas. We won’t be able to do anything close to half in the cities and farm areas. The aggregate of that is a big number.”

You can’t argue Harvey’s not thinking big.

“Minds have been opening to [the idea that] we need to think at a different scale. We need transformative change. These are becoming mainstream ideas.”

Harvey’s right, of course. But is this idea – a proposal known as Nature Needs Half – the right idea?

“Recent scientific assessment by the IPBES (The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) says we’re in a crisis, and we need transformative change. Ideas like Nature Needs Half are transformative ideas. They’re big enough to matter.”

Nature Needs Half wasn’t a catchy slogan picked from thin air. In many ways, Harvey tells us, it’s a vision rooted in science and first proposed by biologist Reed Noss in the 1990s.

“When you look at the studies of how much of a given eco-region needs to be protected if you wanted to save it, the studies were coming in in the range of half. Well, at the time, the global goals were around 10%.”

But, of course, stories rarely begin with a research paper or a scientific study; they begin with an experience that sparks a question needing an answer. Like this one:

“I spent a year studying abroad in Switzerland”, Harvey shares. “But I was stunned over the course of that year to see that it lacked nature. It had beauty but no nature.”

It was an experience that led to a realization, Harvey adds.

“The magic in nature is only there if people ensure that it’s there.”

And Harvey became impassioned about ensuring a place for nature in Alberta and beyond. How? By learning from wild animals.

“We’ve recently learned through the study of the movements of animals and birds – and just a broader understanding of ecology – that the scale at which we must practice conservation is much larger than we once thought.”

Harvey says, think about it this way:

“The wolves in the Canadian Rockies are actually going all over the place. They’re going all the way down into the United States, and they’re going all the way up to Mile Zero of the Alaska Highway. And it’s the same basic pack, or family, of wolves.”

“The wolves in the Canadian Rockies are actually going all over the place. They’re going all the way down into the United States, and they’re going all the way up to Mile Zero of the Alaska Highway. And it’s the same basic pack, or family, of wolves.”

What does that mean? Harvey explains that for him it meant: “I need to be thinking about the scale of Yellowstone (National Park in Wyoming) to Yukon, with how the Canadian Rockies’ Parks sit in that broader framework.”

To help think at that scale, Harvey helped launch the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative.

“The more you study the history, the more you realize people thought it was connected because it was connected. And, so, what we really did is rediscover through biology the natural connections of the landscape at both the human and natural scales – the natural, organic way to think about the region – and it (Yellowstone to Yukon) caught on really fast.”

And yet sloganeering can only take an idea so far.

As Harvey adds, Yellowstone to Yukon “is a big idea that’s a big threat to what is the fundamental dynamic challenge in the region. Is it a resource extraction region like most of the unfarmable areas of North America? Or is it a conservation region, where we think about that first? Or is there some reconciliation of the two?”

“We had a chance to have the big level conversation about reconciling [the two perspectives] – not eliminating one or the other, but reconciling them. A lot of people didn’t want that conversation to occur because they wanted to win an argument that [the region] was dominantly about resource extraction.”

Art Carson is a professional forester and lives just outside of Mount Robson Provincial Park in the Yellowstone to Yukon Corridor. And as Art explains, “Some of the locals have been quite upset at the idea that the area [Mount Robson and other parks in the Canadian Rockies] is not open for logging. They have seen that as basically outsiders putting nature ahead of human beings.”

Art Carson is a professional forester and lives just outside of Mount Robson Provincial Park in the Yellowstone to Yukon Corridor. And as Art explains, “Some of the locals have been quite upset at the idea that the area [Mount Robson and other parks in the Canadian Rockies] is not open for logging. They have seen that as basically outsiders putting nature ahead of human beings.”

And it’s a perspective that shouldn’t be surprising. It’s the kind of community-level opposition that goes hand-in-hand with big ideas. As Art adds, “People do want to be heard, and they want their voices to make a difference.”

And it’s why some – like ocean advocate Diz Glithero – believe big ideas don’t always work. She tells us: “Where I’ve seen the biggest gains is at the local/regional level, and then as you connect the dots, efforts start to dovetail together to have a much larger kind of pan-Canadian effort.”

Former prime minister Kim Campbell has a different take. She says, “I think we need all of it.” But she adds: “It’s really important for people not to feel powerless. That is the most worrisome thing.”

And our former prime minister is right. It’s why people champion local action: To empower people. Still, Kim Campbell also believes that shouldn’t stop us from dreaming – and pursuing big ideas.

“Obviously, there have to be things done on a large scale.”

Harvey Locke agrees.

“So, you need this higher-level vision that looks at what you’re trying to achieve, and then you need people empowered to act at multiple scales underneath that vision. Thinking about all this, how it all comes together, from the local scale to the bigger scale…that’s why visions like Yellowstone to Yukon matter so much to local actions.”

Despite some opposition, Harvey’s big visions – first Yellowstone to Yukon and now Nature Needs Half – are gaining traction and even becoming government policy.

“The idea’s been enduring, and that’s why we’re now still in the game of exploring these reconciliations [balancing resource needs and conservation]. Because in this region, that conversation about nature conservation is in the bloodstream of the people.”

But don’t just take Harvey’s word for it.

Elliott Ingles is the Area Supervisor for Mount Robson Provincial Park. And as he explains, governments now know how important corridors are to conservation.

“That chain of unbroken protected wilderness is vital. It’s so rich in biodiversity.”

Mount Robson, of course, is beautiful and has incredible value to nature. But it’s more than a famous view of a 3,954-metre hunk of rock – the tallest peak in the Canadian Rockies.

This park is also home to four eco-regions – including a rainforest – that sustain the ecosystem’s 182 bird species, its 42 mammals, the four resident amphibians and one species of snake. That’s the biodiversity Elliott speaks of. But as much as this park’s biodiversity matters, it can’t be in a vacuum.

Though Mount Robson is big relative to the size of average parks, it’s not big in the eyes of bears, wolves, cougars, wolverines and other far-ranging animals.

The good news? Elliott says that what makes Mount Robson “really special, I think, is that it’s in the middle of a massive protected area, being Jasper in the East, Kawka in the west. We’ve got a chain of unbroken protected areas through two provinces that enable us to protect that biodiversity.”

The good news? Elliott says that what makes Mount Robson “really special, I think, is that it’s in the middle of a massive protected area, being Jasper in the East, Kawka in the west. We’ve got a chain of unbroken protected areas through two provinces that enable us to protect that biodiversity.”

That, says Harvey, is not only what makes Mount Robson special – it’s what makes every park in the region function naturally.

“The Rocky Mountain parks together have a viable population of grizzly bears. The Rocky Mountain parks individually do not.”

It’s why, for Harvey, the Canadian Rockies are an example of what could and should be done globally.

“I was originally drawn into ‘this is our last best chance’ kind of language. ‘If you can’t do it here, you can’t do it anywhere.’ All those scarcity theories of value where you try to prioritize what you’re doing because it’s special and rare and unique, which is a value proposition in economics. And I came to realize that that’s dead wrong. Yellowstone to Yukon should not be the last of the best, but it should be the first of the next.”

In other words, Harvey believes Yellowstone to Yukon was, or should be, the appetizer to the main course: the global Nature Needs Half proposal. But not every country is willing to set aside half of its landmass; not every politician is willing to go as far as protecting half of Canada.

And yet, current protected area targets are becoming increasingly ambitious, rising from 10% to a new goal of conserving 30% of land and water, both nationally and globally. What’s more, all political parties, spanning the left and right, have affirmed the urgent need to take action to safeguard biodiversity and agree that interconnected protected areas – corridors – are a critical tool to conserve biodiversity.

And guess what? As the UN’s David Cooper explains, our ambition might grow further.

“There is a lot of discussion, yes, about increasing from the present target of 30% [to] perhaps eventually 50%.”

That type of global traction has taken Harvey Locke from biodiversity advocate to adviser to international governments.

“I was appointed chair of a task force to examine what conservation targets should be, exploring whether there can be a consensus around what needs to be done.”

That consensus, however, isn’t and won’t be law, adds David Cooper: “The targets are broadly aspirational at a global level.”

Even still, global institutions – global treaties – aren’t always beloved.

They spark fear and conspiracy theories for some; others see them as elitist and out of touch with reality, while others feel they have no teeth and rarely work. Then there are those who feel global treaties have no teeth and rarely work.

To that, David says: “It’s good to be skeptical. You should be skeptical. You should be skeptical of all levels of government, whether that’s international, national, local. But don’t be cynical.”

Fair counterpoint.

But that’s still not going to sway some people – people who vote, often in swing ridings that determine elections, and create social license for ideas to advance. Or not.

As Sam Sullivan, the former mayor of Vancouver, points out: “People have to have full stomachs before they start caring about the environment. And you can see that in many parts of the world.”

Sam, who also served as a provincial cabinet minister in BC, adds that “even if Nature Needs Half is gaining traction at the international level, the real question is: Will it work at the local level, where aspirational goals will need to become reality? Will we make protecting half of Canada actual policy? Should we?”

Good questions!

It’s about now that you might ask: In a global market system – in a global political system – can one country – small in economic and political mite – really make a dent on this issue?

Well, when it comes to the climate or military intelligence or any number of issues, the blunt answer is probably not. But that’s not the case with biodiversity.

“In Canada, we are ridiculously lucky by the very nature that we only have 39 million people that live in this humongous country.” – Dawn Carr | Nature Advocate

“People began looking at intact forests left in the world, and one of the ones jumped off the page was the boreal forest Canada.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Champion

“Look at Canada. We have this vast boreal forest. We need actually to maintain practically all of that boreal forest and maintain it as boreal forest – whether or not it’s a formal protected area – if we’re going to maintain the life support systems of the planet.” – David Cooper | United Nations

You see, what’s usually seen as a flaw – a small, concentrated population within a vast undeveloped landmass – is our biodiversity superpower. Because of our size, Canada – and a few other nations, like Russia and Brazil (neither of whom are exactly world leaders in advancing global good at the moment) – holds outsized sway when it comes to determining the fate of global biodiversity.

And that’s both our opportunity and our challenge.

For Harvey Locke’s Nature Needs Half vision to work – for the world to provide biodiversity with a margin for error – strong democracies with real biodiversity reserves will need to take one for the team.

But Team Canada? It’s a bit divided at the moment.

Task

What do you think?

Terms & Concepts

Referenced Resources

* Quotes have been edited for brevity and clarity.