Estimated Read Time: 7 minutes

King of Kings

Meet the keystone species that marks the first and last stop on the world’s largest salmon producing river.

By now, especially if you grew up in British Columbia, it’s probably been ingrained in you that salmon matter.

You’ve probably heard it all. That salmon are the ultimate conservationists. That they drive a multi-billion dollar economy. That they sustain communities large and small. That they’re at the heart of numerous cultures. That they’re critical to a healthy diet – and they’re delicious!

But we’re guessing that when you think salmon, you think ocean. Or the coast. Or the rainforest.

You probably don’t think Rocky Mountains. You should.

With apologies to Don Omar (Look! An old school Reggaeton reference!), meet the true king of kings: the Chinook salmon of the Mount Robson ecosystem.

Chinook – known as king salmon to much of the world – are the largest of the five Pacific salmon species (fine, six, if you count steelhead as a salmon and not a trout…fine, seven, if you count sea-run cutthroat as a salmon and not a trout…we’ll leave it to you, fish-heads, to debate that one).

And though they do spend much of their life in the ocean, one special group of Chinook starts and ends its life right here: Rearguard Falls – just over 100 kilometres from the start of the mighty Fraser River on the western slopes of the Alberta-BC border.

Yes, Chinook travel further to spawn (Well, only the one run does, those who call the Yukon River home.) and reach higher elevations (Congratulations, Idaho, you win.). But this is the furthest inland any species travels on the largest salmon producing river in the world, accomplishing both absurd distance and climbing ridiculous heights.

Which is

impressive.

Or insane.

Or both.

I mean, when you’re young, of course you want to get as far away from home as possible. You want to sow your wild oats…er, eat your wild Pacific krill? Anyway, the point being, a nearly 1300-kilometre downhill journey just to get to the start the ocean party makes sense.

But when you’re about to die – having spent years outmanoeuvring orca whales and putting on a lifetime’s worth of body mass – I don’t know if the first thought for most creatures would be to swim upstream 1300 kilometres. I mean if a human just won a food eating competition, they’d likely just want to sleep away the calories afterwards, right?

So, yeah, this run of Chinook do it differently. But are we ever grateful they do.

For starters, that long, rough, cold journey up the Fraser is more than a mating ritual; it’s nature’s cargo shipment (in fairness, for salmon, cold water is key to survival and, for now, the water is cold, so that’s good news for our Chinook friends and bad news for people like Fin Donnelly who, at times, thinks it would be fun to swim with them. But we disgress…).

Like one of those massive freighters carrying cars from overseas (who, ironically, offload their shipments at the mouth of the Fraser), salmon collectively carry millions of kilograms of marine nutrients up the river to feed the headwater ecosystems and, specifically, the trees.

How?

When various animals eat the fish, the rotting carcasses are left on the forest floor and those are the nutrients that go into the soil in order to help the trees grow. In fact, in some cases, 50% of the nitrogen a tree needs to live comes from decomposing salmon carcasses, helping the trees grow at double time.

Bigger trees mean better protection against stream-side erosion (the biggest threat to salmon reproduction) and more help in keeping the water the perfect temperature for future salmon spawning. Bigger trees also provide more carbon storage, more habitat for other animals and more money for the logging industry.

This little partnership is called the nutrient cycle and in the rainforest, the salmon drives it, with a little help from bears and wolves.

But

guess what?

Mount Robson also has a rainforest, as you might have heard.

There have been relatively few studies on the role of this salmon in this rainforest, but what we do know is that all salmon in all ecosystems they traverse contribute to healthier forests and healthier ecosystems.

Even when salmon decompose in the rivers, they greatly increase the organic matter in the water, which also helps the ecosystem far and wide – upstream and downstream.

It’s why 137 species, ranging from zooplankton to grizzlies, are impacted by this fish – and probably no more so than the critically endangered southern resident killer whale. In fact, the fate of this whale population is directly tied to Fraser River Chinook runs. Even if it starts and ends its life hundreds of kilometres away from the ocean, what happens to salmon in the Robson Valley – and what happens in the Robson Valley that impacts salmon – will play a major role in the survival of the southern resident killer whale.

So to recap: salmon sustain the hydrology, the geology, the geography and the biology of everywhere they’re found. And you probably knew some of that, but it bears repeating, especially when you consider half of Chinook salmon runs are now endangered and the other half are in decline.

That goes to show you: no matter how much we talk about the awesomeness of salmon, we still seem to be forgetting that just because they are awesome doesn’t mean their future is awesome unless we do something awesome to help them.

And we all can and should do something to help. (Rid a freshwater ecosystem of invasive zebra mussels like Gail Wallin! Rehabilitate a stream like Bruce Wilkinson! Think more carefully about the sushi you order like Quinn Scott!) – After all, the very existence of this Chinook migration is nothing short of a miracle.

I mean, think about it. The salmon know to migrate down the Fraser to set up shop in the ocean when they’re born and know to return to the exact spot where they were born to reproduce and die.

Like, imagine finding the right estuary at the mouth of their river – there are literally thousands up and down the coast.

Like, imagine coming to the intersection of the Thompson and Fraser Rivers – it’s a 50/50 choice and many humans, with the more evolved brains, would guess wrong and find themselves in Adams River with a bunch of Sockeye when they should be at Rearguard Falls and all the Chinook are, like, where’d ya go, mate?

The reason it’s a miracle? Because of another miracle: salmon being born master chemists.

The Chinook, at an equivalent age to when we can’t even figure out how to operate our limbs, understand the exact chemistry of the river where they were born. And it’s the distinct chemistry of an individual river – an individual location on a river – that they memorize and keep with them during their journey downstream, during their extensive run at the ocean’s increasingly dwindling crustacean buffet, during their frantic swim away from the orca whale, and (finally) during their second-longest-on-planet-Earth journey up – and, again, we emphasize up – the Fraser River to where they spawn.

Which is really cool.

Not so cool? The fact that the best Chinook spawning ground is just up and over the 50 metre high Rearguard Falls, which seems like an especially cruel April fool’s joke in September without a punch line.

And that’s why some salmon just call it a day and spawn below the falls, because, seriously, they must be tired and, at that point, be seriously reconsidering the point of it all.

But, by some (again) miracle, many jump the falls. For them, they’re probably dumbfounded that their fellow Chinook would swim all the way to Rearguard – risking near death, at times – only to call it quits right before the end.

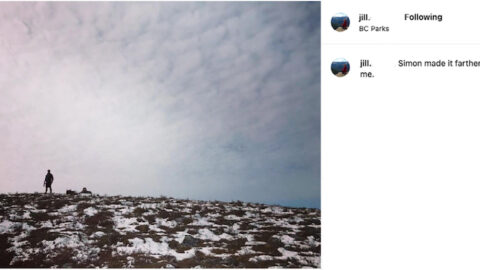

It’s probably similar to when Jill hikes a mountain with Simon, only to call it a day a mere 100 metres before the end of the hike, missing the incredible, incredible view.

(And, in case you’re wondering, the view is actually better from below the falls rather than from above, but no Chinook needs to know that.)

But the point remains: this Chinook run is a miracle and they don’t just sustain the Mount Robson ecosystem, the large Fraser Basin watershed or the southern resident killer whales, they sustain us all, no matter where we live. Which is why, truly, they are the king of kings.