Three provincial elections down and one to go. What have we learned?

Change Meets Incumbency

It seems that ever since COVID came into our lives, we’ve been living in a time of great uncertainty and mass change. History shows us that during times like these, people are (understandably) fearful of what the future holds. And when we fear the change tomorrow will bring? We place (an often desperate) hope in, ironically, change itself.

We seek out leaders who are different from the ones who currently lead us. We care less about left-versus-right and far more about changing the direction of society, no matter what that direction actually is. After all, different might be better and that’s the stuff that drives hope. And when there is this kind of desperate desire for change gaining momentum, it can even overcome the power of incumbency.

The power of incumbency?

Yes, because other than a desire for change, incumbency might be the most potent political force that exists.

Think about it: the incumbent has name recognition, which matters far more than it should in our elections. More than that, incumbents are also known entities. We know what the incumbent stands for, even if we might not fully embrace their values. The promise of stability – and the fear of the instability that comes with an unproven commodity – has won more elections than any policy promises in Canadian history.

And don’t forget about the advantages of power. Spending money to implement ideas always beats the promise of an even better idea. Running ads, handing out cheques, cutting ribbons, being the face of good news? These are all incumbent advantages, along with the understanding of how to fight a successful campaign.

Often, the only way incumbents lose is when they defeat themselves. After years in power, incumbents get complacent, and they accumulate baggage and scandals. The collective weight of their own arrogance, more than an appealing alternate vision, is what actually brings down an incumbent government.

Unless, of course, events beget an urgent desire for change.

This past year has seen more elections take place across the world than at any point in history. And in the elections that were fair and democratic, change (at least in some form) trumped incumbency almost every time.

But what about here at home? Well, three provincial elections in a week gave us the chance to see what is a more powerful motivator for Canadians: change or incumbency.

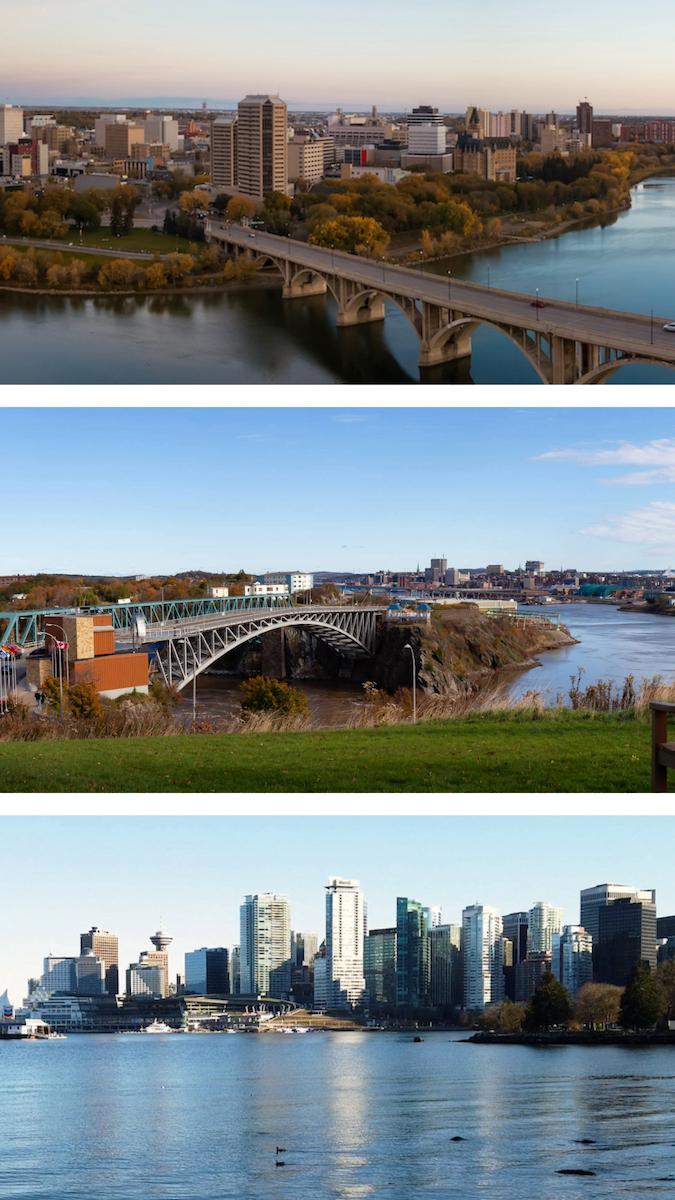

Scott Moe’s Saskatchewan Party was supposed to romp to victory in their reliably conservative province. But that didn’t happen. The NDP surged, dropping the incumbent’s vote total province-wide and tightened so many races in urban centres that it was almost midnight before we knew who won the Saskatchewan election.

In New Brunswick, Blaine Higgs and his Progressive Conservative Party thought they could avoid the winds of change. Nope. Susan Holt and the New Brunswick Liberals resoundingly defeated Higgs, forming a majority despite the fact that the Liberal brand is historically unpopular thanks to their Trudeau-led federal cousins.

And then there is BC. David Eby’s BC NDP thought they would coast to re-election, facing a divided right. That also didn’t happen. Though they hung on to power, they came within a few votes of losing to a party (not an ideology) that hasn’t formed government in nearly a century.

So, yeah, Canadians clearly wanted change, right? Well…

Blaine Higgs consistently polled as the least popular premier in Canada. His political baggage was legion, even leading to divides within his own party. Is it actually all that remarkable that the Progressive Conservatives lost the New Brunswick election, especially given that Higgs couldn’t even hold onto his seat? Yes, the electorate wanted change, but possibly not because of the times we live in. It’s possible this is a case of the incumbent defeating himself.

In Saskatchewan, yes, the NDP had their best showing in twenty years. And, yes, they made several races close, at least temporarily causing some to wonder if they could pull off an upset. But an upset isn’t quite what change elections are all about. Change elections feel inevitable. This wasn’t that.

Though the NDP increased their popular vote, they still lost 53%-39.5%. Bluntly, that’s not close. And though they also increased their seat share, they did so by having a very efficient vote. Their voters were highly concentrated in enough ridings to potentially form government, but they weren’t a threat to be the popular choice province-wide. (Remember, friends, when we criticize our electoral system, it cuts both ways. Sometimes our system benefits conservatives, and sometimes it benefits progressives. Rarely does one side benefit more than the other.)

Plus, the Saskatchewan Party has been re-elected to their fifth straight majority. That’s an incredibly rare feat for any party, in any province. Incumbents almost always defeat themselves after holding power for nearly two decades. Yet despite having accumulated ample political baggage, the Saskatchewan Party will reign for four more years, winning in an election year that, we’re told, is all about change.

Interestingly, it might be BC that best exemplifies a change election.

Yes, the NDP won – and, yes, they might even win a razor thin majority. But the BC Conservatives didn’t win a single seat in the previous election. In this one? They came within a few hundred votes of winning it all.

Moreover, the Conservatives were led in the election by a recent political nomad, John Rustad, who was kicked out of the BC Liberal-turned-BC United caucus for doubting man-made climate change. He didn’t just revive a dormant party brand, he eventually swallowed whole the BC Liberal-turned-BC United Party. That shotgun wedding left some feeling alienated; it led to independent candidates running in ridings that split the vote, helping the NDP win.

Then there’s this: the BC Conservatives were so new to competition that they lacked the data – and the experience and knowledge – to win an election. They ran a slate of candidates that clearly weren’t well-vetted and, yet, even in the face of stumble-after-error-after-stumble they still came within votes of governing the province.

The point being? While the NDP were re-elected in BC, if they had run against a party (possibly even led by a different leader) with more time and experience and knowledge to build a better campaign, the BC Conservatives likely would have won the election.

So, what does this all mean? Are Canadians yearning for change? Or is incumbency still more powerful? Well, it’s a mixed bag, as you can see. Maybe Nova Scotia will give us a clearer answer; maybe they’ll break the tie.

Until then, beware of absolutist narratives, for they are rarely right.

Yes, Canadians might want change. And, yes, maybe they still value stability. Yes, maybe Canadians are becoming more conservative. And, yes, conservative popularity might be more about being in the right place at the right time. There is a case to be made for all of these statements in the wake of the recent provincial elections. But to really understand our current political climate, rather than to just prove a point, we need to dig deeper to uncover the nuance.

That’s true for those who govern our country (or seek to), just as it’s true for those learning how we govern our country. After all, it’s hard to advance ideas – or complain about those others are advancing – if we don’t understand the fine print.

Two More Thoughts

Political (Il)literacy

In the wake of BC’s epically close election, it’s clear too few understand how our political system works.

Here are just a few questions we’ve seen circulating:

- How and when are recounts conducted? (They’re overseen by the judiciary when races are decided by fewer than 100 votes, or when a close race is successfully challenged in court.)

- Who is our provincial head of state? (The Governor General-appointed Lieutenant Governor.)

- What role does the Lieutenant Governor play in determining who gets to form a provincial government? (In a minority government scenario, the Lieutenant Governor determines which political party should get the first chance at proving they can govern with the confidence of the legislature. Usually this is the party that has won the most seats in the election, even if they are shy of a majority.)

- What constitutionally-enshrined avenues exist for political parties to govern in a minority government situation? (Supply-and-Confidence Agreements with opposition parties that promise legislation in exchange for votes in all confidence matters are common and legitimate. Less common coalition governments, with opposition legislators taking cabinet positions, are also legal and legitimate in our system of government.)

- Must a Speaker be selected from the governing party’s caucus and can they vote on legislation? (Any member of the legislature can be selected Speaker, but if opposition parties don’t want to help the government remain in power, they can force the governing party to select a Speaker from within their own ranks. This is a problem if the government caucus only enjoys a bare majority. While the Speaker can vote with the government on matters of confidence, their role is supposed to be non-partisan and, thus, they often won’t vote and break ties unless the government itself can be brought down. In BC, even with a slim majority government, if the Speaker is selected from their caucus, the NDP will likely need help from the BC Green Party’s two MLAs if they hope to pass legislation.)

When you’re in school? You should be asking these questions. When you’re an adult voter? You should know the answers to these questions. After all, what’s at stake isn’t only who gets to govern, but the fate of our democracy as well.

Why?

Well, when we don’t understand our system, we make faulty assumptions and accusations. We’re also more susceptible to fake news and misinformation designed specifically to draw us into echo chambers. The consequence of all of this is an increasing number of voters who feel our system is corrupt. And when the seeds of mistrust are sewn, our democracy falters and frays.

For this reason, it’s why we’ve spent so long covering the provincial elections – the terms, the procedures, the obligations, the context and consequences. Even if you don’t love this stuff – even if you find it boring and confusing – take the time now to really understand how we’ve elected to govern our society. You owe it to your future self, your future society. And you owe it to our democracy, and to all of those who have died to sustain it.

And if you’re still struggling to understand our complex system after our numerous videos? That’s fine! But don’t quit trying to understand. To that end, maybe these articles will help:

Final vote count shows bare majority of 47 seats for B.C. NDP

Parliamentary Democracy 101 in British Columbia — Know the Rules and Ignore the Bullshit

The Urban-Rural Divide

Look, we know we’ve beaten this horse to death. Everyone acknowledges that the urban-rural divide exists. No, it’s not new. Yes, it’s more pronounced and growing. But here’s the thing: even though it threatens to rip our country apart, no one is actually seeking a solution.

On Saskatchewan’s election night, a former Saskatchewan Party cabinet minister told a reporter that she’s concerned about the growing divide. When asked what should be done, she essentially suggested better communication might be required.

Well, sure, okay.

Communication matters. Heck, we even devoted an entire chapter in Nature Labs to better communication. But while re-framing and better communicating an issue might help on a superficial level, it won’t really tackle the root of the problem.

Think about it this way: even if better communication can help forster common ground around, say, education or health care (and that’s a big maybe), it ignores the other issues that are really bringing the culture war to a boiling point. Those issues can’t be ignored. Without finding common ground on the bigger, more contentious issues, the problem will only fester.

Our suggestion? Remember that communication isn’t just about how an idea is presented, it’s also about really listening to other perspectives.

And we always forget the listening part. Left and right, urban and rural.

We’re so focused on getting the result we want to see, we neglect the much harder work of asking those with opposing views why they feel the way they feel. And we almost never work to include at least aspects of opposing views in our ideas. We rarely work to find the seeds of reasonableness that are almost always buried deep within unreasonable, rigid ideas.

If we want to heal the urban-rural divide? This is where we need to start.

And it needs to be a shared goal – a shared challenge – by government and opposition, by rural citizens and urban citizens. More importantly, it needs to be a challenge you accept and take on as well. For if we want less divisive elections and electoral outcomes? Building bridges into communities we desperately want to overlook is an imperative. The recent provincial elections have only served to reemphasize this point.