Estimated Read Time: 39 minutes

Canada at a Crossroads

Here’s a question: What is the Canadian identity?

Here’s a question: What is the Canadian identity?

“We’re still asking that question, and we always will. It’s not unhealthy that we continue to do that.” – Peter Biro | Lawyer and Democracy Expert

But so often how we define ourselves – what we think we can rally behind – is different from what our neighbours value. This reality leaves our nation susceptible to the division we see, for we haven’t settled on a uniting vision. And while Canadian nationalism is certainly having a moment, as demographics expert Hamish Marshall argues:

“We need to build an identity that is actually not just based on not being American.”

Hamish is right. Not being American isn’t an identity. But even going back to before confederation, standing against America – being different than the US – has always been a Canadian rallying cry.

“Obviously, there’s incredible cultural similarities between us and Americans and so much of our Canadian identity seems to come down to – we’re like Americans, but we’re somehow morally superior to them. And I don’t think that’s good enough. I think that’s sort of a weird way of defining ourselves. We have to come up with a way, and I don’t say I have the answer, but we have to come up with a vision of ourselves without comparing ourselves to the United States. A vision that exists on its own about who we are and why we are a country.”

Think about it:

Canada began as a colony of the British Empire, serving as an English bulwark against the American republic and its rebellion against British rule. As Canadians gradually forged a separate identity, this process was often shaped by a desire to distinguish ourselves from the United States and the monolithic culture emerging from the south.

Ask Canadians what they’re most proud of? They don’t wax poetic about the inventions of insulin or the telephone, but rather staying out of the Iraq War or beating the US at a hockey game. Even building the transcontinental railway, a project to unite the young nation, was partly motivated by a goal to block American railroad barons and their manifest destiny ambitions.

In other words, Canadian identity has long seemed to focus on opposition rather than uniqueness. As if standing against something, rather than standing for something, is reason enough to justify sovereignty.

In other words, Canadian identity has long seemed to focus on opposition rather than uniqueness. As if standing against something, rather than standing for something, is reason enough to justify sovereignty.

It’s not.

“Maybe the only good thing that can come out of this current situation is some courageous people start laying out what a real Canadian identity could look like, and it to take hold. The arc of history is not bent this way, maybe it’ll bend the other way.” – Hamish Marshall | Conservative Strategist

It’s why before we settle on a direction forward as a nation, we really first must understand who we are as a people. We need a common starting point – a shared identity that can helps us navigate this moment, together.

“I think it’s always about identity and meaning. It’s about having a sense that you matter and that who you are matters and that you have a place in the world where you can do something that’s meaningful.” – Ilona Dougherty | Youth Advocate

“We’ve got to believe in going somewhere if you want to get something done, you have to have a social direction. We want to figure out what this means. And there’ll be stumbles and falls, but mostly there’ll be progress as we move towards something good.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“We are empathetic, we are kind. That shouldn’t change. But what needs to change is we need to start believing in ourselves more as a country – knowing what we’re really good at.” – Ilona Dougherty | Youth Advocate

“That confidence from that vision, if it gets brought by and across the country – across political parties – will give us the confidence to make decisions for our international interest, because we’ll know what our national interests are in a meaningful way, as opposed to everybody claiming national character is just a political football to score some points.” – Hamish Marshall | Conservative Strategist

Where to begin? Well, probably right here – wherever here is for you. After all, our shared identity starts with where we stand. Our land.

Where to begin? Well, probably right here – wherever here is for you. After all, our shared identity starts with where we stand. Our land.

Of course, land – home – is central to most cultural identities. It’s what links geography with history and experience to provide a sense of belonging in this world.

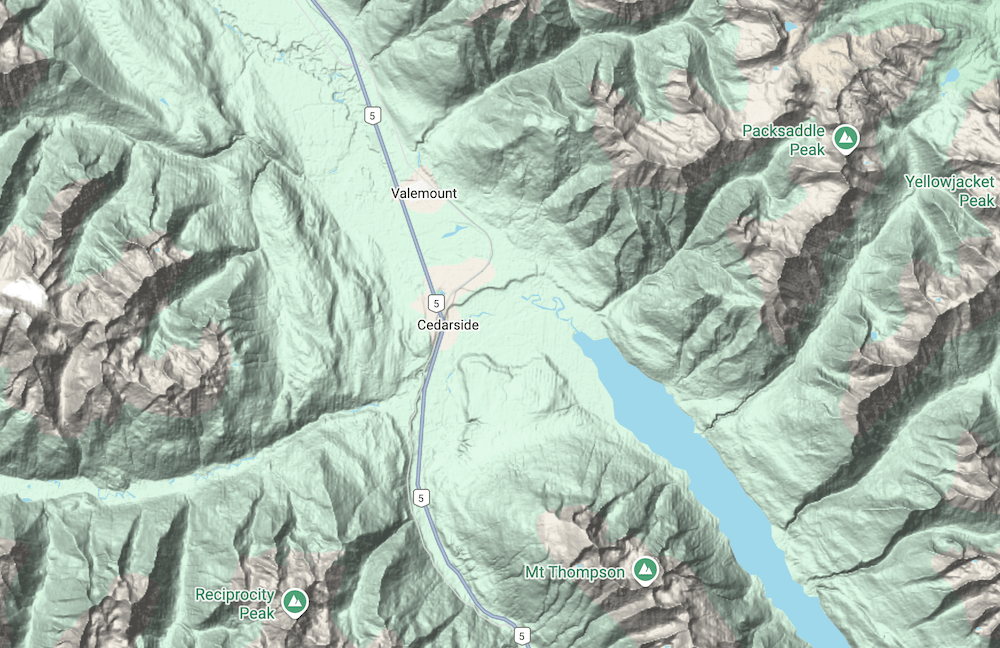

But here’s the thing: land is a complex subject. To understand, let’s step back into your classroom and follow the waterways from Mount Robson south to the community of Valemount and shores of Kinbasket Lake, where historical issues of land, identity, and sovereignty are coming full circle.

“In 1877, that is when (a major) treaty was signed, which then put several First Nations communities on reserves. That freed up a lot of land and settlers came.”

As settlers moved into the west, little thought was given to Indigenous sovereignty, but a whole heck of a lot of time was spent fretting about Canadian sovereignty. The government saw an urgent need to unite western settlers under a common national banner to prevent American territorial expansion. The key to that? Construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

“It starts construction in 1881 and it finishes in 1885.” – Sierra Daken Kuiper | Cultural Anthropologist

Though surveyors recommended a route across your classroom, Mount Robson, the lower elevation Yellowhead Pass found in present day Mount Robson Provincial Park, the government – subsidizing the CPR’s construction in the name of national unity – preferred Kicking Horse Pass much further to the south.

Though surveyors recommended a route across your classroom, Mount Robson, the lower elevation Yellowhead Pass found in present day Mount Robson Provincial Park, the government – subsidizing the CPR’s construction in the name of national unity – preferred Kicking Horse Pass much further to the south.

This decision was strategic: the US-owned Great Northern Railway was eyeing large parts of present-day British Columbia, and the Canadian government wanted to physically secure the southwestern border with a railway corridor that would discourage American encroachment.

In the rush to assert control, King George’s Royal Proclamation of 1775 – which recognized Indigenous land rights – was largely ignored in BC.

“And when that railroad is finished, that last spike is drilled in British Columbia, we can see a clear timeline of the expansion of Canada in displacing indigenous peoples from their homelands.” – Sierra Daken Kuiper | Cultural Anthropologist

Land was taken from Indigenous nations without consent to make way for the railway and the settlements it spurred.

Fast forward several decades.

Despite growing economic and cultural ties, Canadians remained wary of American interests – particularly their interest in our natural resources.

Indeed, disputes over transboundary water management – such as the Columbia River system – became a flashpoint in U.S.-Canada relations by the 1960s. The US sought to flood large areas of eastern British Columbia to ensure water security and generate hydroelectric power for its drier western states, including California.

The anti-American sentiment found within our national identity fuelled Canadian resistance, leading to a compromise: the 1964 Columbia River Treaty.

It dictated that the Columbia River be dammed near the CPR line, creating Kinbasket Lake – a reservoir that flooded an area that stretches all the way north to the Robson Valley and the community of Valemount.

It dictated that the Columbia River be dammed near the CPR line, creating Kinbasket Lake – a reservoir that flooded an area that stretches all the way north to the Robson Valley and the community of Valemount.

While the treaty enabled Canada to maximize hydroelectric production, a major driver was the provision of reliable flood control and power supply downstream in the United States – benefits which, at the time, outweighed direct Canadian needs.

Oh! And indigenous rights.

In British Columbia, of course, sovereign Indigenous Nations never signed treaties and were neither consulted nor consented to the flooding of their traditional territories. The formation of Kinbasket Lake submerged vast stretches of land belonging to the Secwepemc, Ktunaxa, and Syilx peoples, destroying homelands, sacred sites, and traditional livelihoods.

Indigenous communities strongly opposed the dam, arguing their interests were ignored when Kinbasket Lake was created – a situation made possible by the fact that it happened before Canada repatriated its constitution from Britan and affirmed Indigenous rights through Section 35 in 1982.

This isn’t just a history lesson, of course.

US President Donald Trump has been reluctant to sign a new Columbia River Treaty, which governs the future use of the river system and reservoirs like Kinbasket Lake. In fact, Trump specifically cited water resources and the Columbia as one justification for annexing Canada as America’s 51st state, adding that he would also use the unrenewed Columbia River Treaty as leverage in the tariff dispute between our two nations.

Why? Canada has enormous water resources, whereas America doesn’t. If we could be convinced – convinced? extorted? – into creating a few more Kinbasket Lakes, or at least relinquishing some control of our water management, a Trump White House would be more than pleased.

Which is as outrageous as it is ironic. Blackmailing a sovereign nation for control over resources? Annexing land to benefit the needs of a more powerful nation? Sounds very similar to the circumstances that led-up to the construction of the CPR and the flooding of Kinbasket Lake.

See? We’ve indeed come full circle on the shores of Kinbasket Lake. And it’s against this backdrop, we need to remember the words of Indigenous leader Larry Casper.

As he told us, quote, “We all are inherently úcwalmicw (the people of the land), wherever you originate from.”

As he told us, quote, “We all are inherently úcwalmicw (the people of the land), wherever you originate from.”

Larry Casper is a member of the St’át’imc nation and has been an advocate for his people and his land – our people and our land – for much of his life. Indeed, caring for this land matters deeply to his people because of their history on this land.

“(The St’át’imc and Indigenous connection to place) stems from the historical length of time that the St’át’imc have lived on this land…It seems only natural that a relative newcomer population would not share this same connection to the land, as they have not been here long enough to establish this deep relationship.”

Which is an important insight. So too is this:

“The St’át’imc world view of ownership of land or territory still varies from the modern practice of fee simple or site-specific ownership of land and/or properties…We are more like “caretakers” of the land for the benefit of our future generations.”

And yet site-specific ownership of land is very much how western society works. And the disputes over ownership is at the heart of what frustrates Larry Casper and so many Indigenous communities.

“Mainstream society would benefit from learning about the European based doctrine of consent, or terra nullius, which characterizes that the land is empty, as the racist basis for European/Canadian governments to claim ownership of our Indigenous territories.”

The rejection of terra nullius is actually one of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action and since that particular call to action hasn’t been acted upon, it’s one reason why Larry feels “the federal/provincial governments still have a long way to go in recognizing us as a full partner in the land we all live in.”

Remember, truth and reconciliation is about honest history and respect, absolutely, but it’s also about land – and cultural rights and determination of that land.

Like what happens to this lake moving forward – and who gets to have the final say. After all, given the lack of treaties signed in present-day BC, to address issues of Canadian sovereignty we must first address issues of Indigenous sovereignty.

Indigenous leader Kory Wilson wasn’t able to speak with Nature Labs before we published this story, but she told the CBC, quote:

“Indigenous sovereignty is the original sovereignty.”

And with the inclusion of Section 35 in our constitution and adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as law federally, Canada’s courts increasingly are giving expression to the idea of Indigenous sovereignty.

Kira Wilson, an Indigenous leader with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs explained to the CBC, quote, “First Nations are not stakeholders — we are the foundational Nations of these lands … Canada’s future cannot be built without First Nations leadership at the centre.”

You see, as Canada pursues nation-building projects to safeguard our sovereignty – including projects like a national energy corridor near the northern shores of Kinbasket Lake – critics fear that urgent national interests will override Indigenous rights, just as was the case during the construction of the CPR and the flooding of Kinbasket Lake. For others, of course, the need to act quickly and decisively mirrors an age-old fear: America’s wants and needs.

But as Kory Wilson told the CBC, quote:

“Sovereignty isn’t about ownership and about sole determination. It’s about working together, living together and allowing people to be self-determining … pursuing their own interests and working together to keep this country stronger and not the 51st state of the United States.”

In other words, as a nation, we need to be able to recognize the urgent threats posed by America while also upholding our constitution obligations to consult Indigenous nations.

In other words, as a nation, we need to be able to recognize the urgent threats posed by America while also upholding our constitution obligations to consult Indigenous nations.

As Kory Wilson added to the CBC, quote:

“Sometimes people think, well, if we include Indigenous people, then I’m not going to have this, or we’re going to lose X, Y, and Z. There’s no pie. If we don’t do it together, it’s not going to work… Let us put our people to work and help and support and move this country forward.”

And Indigenous leader Melanie Mark agrees, adding to the CBC, quote:

“If we take a more collaborative approach, we’re going to have a win-win for all Canadians – whether that’s resource development, job creation, the list goes on, but we have to be working together, and time is of the essence.”

And that’s true. But guess what isn’t quick? The legal system and a recent court decision in BC has likely made an already complicated process more complicated.

The BC Supreme Court has recognized the Cowichan Nation’s Aboriginal title over hundreds of acres in Richmond, a suburb of Vancouver.

Notably, the court declared that many Crown-granted fee simple land titles – essentially privately owned land – were unjustifiably infringing on Cowichan Aboriginal title and thus deemed invalid. Although the court did not invalidate private property outright, it affirmed that the province has a constitutional duty to negotiate in good faith with the Cowichan Nation to reconcile private land ownership with Aboriginal title.

In BC, where few treaties exist, who owns what and where – in western societal terms – was already complex when it came to Crown or public land. But this case – which will be challenged in our federal Supreme Court – adds a new wrinkle, raising the question of how private land ownership can co-exist with Indigenous land rights on territories lacking a treaty.

If you thought complex governance structures, the byproduct of the racist Indian Act, and a constitutional requirement for our governments to consult with Indigenous nations was already slowing down major projects in this country, well this court decision isn’t going to make the new build baby build mantra any easier to pursue.

But Melanie Mark, a former BC NDP cabinet minister, wants you to understand this:

She told the CBC, quote, “I’m a proud Canadian. I love hearing ‘elbows up’ and that we’ve got a Team Canada approach, but we can’t keep benching First Nations people in this conversation. We need to be working with Indigenous leaders.”

Economy expert Heather Scoffield agrees there are no short-cuts when it comes to our relationship with Canada’s first peoples.

“You start talking about pipelines and it gets difficult because pipelines go across a lot of a lot of land, a lot of different areas. It’s not straightforward. That land, when you go across kilometers and kilometers, it’s not all just going to be land that the company owns, so you’ve got to negotiate that with every single community along the way. It’s hard work. It’s got to be done. There are no shortcuts, which is frustrating to some parts of the business of pipelines – because they do want to get it done really fast.

It’s not just frustrating to pipeline companies though; this reality also frustrates provinces.

“I am deeply concerned about confederation in Canada.”

Donna Kennedy Glans is a former Alberta cabinet minister and headed up the Alberta Fair Deal Panel, which sought to hear the grievances of Albertans frustrated, in part, by delays to projects that have impacted the regional economy.

Donna argues that just as we need to understand the connection between Indigenous identity and land, we also need to understand how land influences the identity of so many others.

“We have layers and layers of identity and values that come to us from the way we’re raised, from the people we love and respect, from the place where we live.”

In other words, while a love of land might be a common starting point for all citizens of this land, how and why we love the land will inevitably vary from person to person, culture to culture, and place to place.

After all, just think about Kinbasket Lake. The layered history of this place spotlights how differing conceptions of land – seen alternately as a commodity, a spiritual home, and a national asset – continue to shape our ideas of identity and sovereignty.

But Canada doesn’t just need to reconcile issues of Indigenous identity and sovereignty.

“Nationalism has meant, in the Quebec context, the advancement and the protection of the values and the identity of the Quebec nation.”

Right, the Quebec nation! As lawyer and constitutional scholar Peter Biro explains:

“What constitutes a Quebec nation continues to be a matter of rich discussion. But we know for sure that they have a lot to do with – first of all, the French language to some extent. Historically – to a very great extent – it had a lot to do with the Catholic Church. How that accommodates a diverse demographic has been the big problem, not just the Anglophones, but the Allophones, and not just the Protestants, but the Jews and the Muslims and others who are not French Catholic – who are not purebred Quebecois.”

“What constitutes a Quebec nation continues to be a matter of rich discussion. But we know for sure that they have a lot to do with – first of all, the French language to some extent. Historically – to a very great extent – it had a lot to do with the Catholic Church. How that accommodates a diverse demographic has been the big problem, not just the Anglophones, but the Allophones, and not just the Protestants, but the Jews and the Muslims and others who are not French Catholic – who are not purebred Quebecois.”

That friction, of course, has, at times, divided our nation and clouded our ability to find a unifying national identity.

“Quebec is a democracy. It’s a province. It’s got exclusive jurisdiction over a whole host of things, as do all the provinces. In their universe of provincial jurisdiction, they’ve decided to deal with some questions; about diversity, about secularism, about freedom of religion and expression, differently than the way that communities in other parts of the country have chosen to do it. That’s healthy in a liberal democracy – for those kinds of diverse approaches to be expressed.”

And while it might be healthy? Peter says:

“In terms of stewarding our democracy, you can see the challenges right there. You’ve got members of different communities and different backgrounds who are part of the Quebecois demographic and are trying to live as self-governing members of Quebec society, respecting the will of the general population while also protecting the interests of the minorities.”

It’s complicated and it continues to complicate our ability to find a shared identity.

“The challenge for Canada and for Quebec has been how to remain a cohesive single country while preserving the cultural distinctness and to some degree even the political distinctness of Quebec, how to give voice and expression to those nationalist aspirations while still respecting or while not infringing fundamental rights and freedoms. It’s a dance. It’s a delicate dance between cultures and communities, and it’s also a dance between elected officials and the courts. There’s constant adjustments and readjustments and repositioning that takes place.”

What kind of adjustments?

Well, we’ve recognized Quebec as a distinct nation within the larger nation of Canada, but even with this declaration, Quebec remains the only province to have not signed our constitution. Indeed, for some Quebecers, nothing short of separating from Canada will be sufficient to protect the Quebecois identity.

Emphasis on some, because support for Quebec independence has shifted, explains demographics expert Hamish Marshall.

“The numbers have changed and support for Quebec sovereignty is much lower than it was, certainly than when I was growing up. These regions aren’t as monolithic as they were.”

And while that’s good news for Canada, if we’ve learned anything from recent events, it should be to take nothing for granted.

A Quebec referendum on independence? It could still happen. And as journalist Paul Wells wrote in a Substack post, quote:

“The instruction manual for politics in the 21st century is a single page, on which is written, DON’T ASSUME THE BEST.”

And while we shouldn’t make assumptions about Quebec, we also shouldn’t make assumptions about the prairie west.

Alberta? Saskatchewan? And, yes, even pockets of BC? They too increasingly see themselves as a nation within a nation, believing they have a unique identity worthy of protection – one also focused on land and the right to self-determination.

The perceived lack of respect for this reality has led to political strife in the prairie west. Some have expressed a desire to become the 51st US state and while others have raised the spectre of a referendum on separation.

Preston Manning, the founder of the Reform Party, wrote an opinion editorial during the last election, stating, quote:

“Voters, particularly in central and Atlantic Canada, need to recognize that a vote for the Carney Liberals is a vote for Western secession — a vote for the breakup of Canada as we know it.”

Indeed, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith made a citizen-led vote on Alberta secession possible by lowering the threshold needed to trigger a referendum, telling the CBC, quote, “I have simply stated that I will respect the process”, while confirming that her government would hold a referendum on separation if just 10% of Albertans sign a petition.

Is this an issue we should be concerned about? YES!

“And what I would say there and is a very, very critical – an under-appreciated national unity crisis on the horizon there with Alberta. We focused a great deal on Quebec in Canada. We’re focusing more and more now on First Nations. We’ve kind of skated over the west just on the assumption that that problem is going to be there, but they’re not really going to go anywhere at the end of the day a I think that’s probably incorrect, but even if it’s not, it’s most definitely the wrong way to approach nation building.” – Peter Biro | Lawyer and Democracy Expert

“In my first conversation as opposition leader with Prime Minister Trudeau, I raised concerns about western alienation and feelings of separation anxiety, and I was widely mocked by the Globe and Mail and other sort of national news sites by overstating concerns about unity, while today, we see the results of ignoring that problem.” – Erin O’Toole | Former Leader of the Conservative Party

And while this might be a growing problem, it isn’t a new problem, argues Conservative strategist Hamish Marshall

So, let’s better understand the root of this discontent.

“The desire for sovereignty in the west and the prairies, for some people there, it’s long standing.”

Monte Solberg is a proud Albertan and a former federal Conservative cabinet minister.

“Western alienations goes way back.”

That, obviously, is context for this:

“In 1905 when Alberta and Saskatchewan became a province, we were the western provinces, not having control over our natural resources. Unlike central Canadian provinces – Ontario, Quebec and the maritime provinces, not including Newfoundland. At the time, they all had control over natural resources, but the western provinces were denied that until 1930. It took 25 years of fighting to get the same control over natural resources that the other provinces had. That obviously is context for this, the 1981 National Energy Program. It was a complete disaster. People lost their homes, people lost their businesses. It’s important to remember back on how serious it was.”

Ah, the National Energy Program (NEP).

You see, Alberta has long believed it has had to fight for everything it has. And while that’s a regional perception, it’s also fact.

It was, after all, Alberta’s fighting spirit that allowed the province to carve out an oil and gas economy from boggy boreal forest in the northeast corner of the province, bringing incredible prosperity to all of Canada. And, at times, Alberta has delivered Canadian prosperity at the expense of, well, Albertans.

The National Energy Program was introduced by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s government in 1980 and designed to increase Canadian control over the oil and gas industry, secure national energy independence, and ensure fair energy prices. But many in Alberta, rightly, viewed the NEP as a federal intrusion on provincial jurisdiction and a move to redirect resource revenues from the West to benefit eastern Canada, leading to intense resentment and economic fall-out in the vacuum of uncertainty the policy created.

“Pierre Trudeau, his name was not held in high esteem. We’ll put it that way.”

And as Monte Solberg explains, for Albertans, Justin Trudeau’s election was like father like son.

“Both presided as prime minister at a time when the energy industry really just did take a beating. And Justin Trudeau, I think, was a complete disaster for Western Canada. It was sort of this passive aggressive approach about wanting to cooperate on things like energy, but just refusing to recognize that there needed to be an economic case needed to be able to make a profit while addressing environmental issues, and that was never fully recognized.”

This latest chapter in the western alienation story is partly why we see a political – and separatist – movement rising up to defend Albertan interests. But it’s not the first political movement to rise up to give voice to western frustration, as Monte explains.

“I remember very clearly the CF-18 fighter deal of 1986 where a contract had been awarded to a firm in Winnipeg, and that was taken away from the Winnipeg company and moved to bombardier in Montreal. This started a grass fire on the prairies. People were just so upset. Once again to them, it seemed as though that the west was losing out and the east or central Canada was being favoured. So that was really the genesis, in my mind, of the rise of the Reform Party. We rallied around a slogan, ‘The West Wants In’. But really the essence of it was ensuring that western voices were reflected in the House of Commons set an important example for a positive channeling of western frustration.”

And that’s true, but as Conservative strategist Hamish Marshall points out:

“It could have gone a different way. I think the danger moment could have been when the Reform Party first was first created. It obviously didn’t turn into an independence movement. And ultimately, was good for the unity of the country.”

What about today’s separatist threat in Alberta?

“Most polling shows it’s tops out somewhere in the low 20s when you really push into how people feel about it.”

To that base of support, Monte Solberg, one of Canada’s first elected Reform Party MPs, says:

“We know it’s working. We’re getting there, and we can’t just be put off by a prime minister in the past who just refused to work with us. And to me, that doesn’t mean that Confederation is broken. It means that we need a determination to make Canada a better country, not to break it apart.”

Biodiversity advocate Harvey Locke goes further.

“I was born in Alberta. My family were Albertans since before the creation of provinces. This separatist nonsense, I think it’s actively destructive. When people say they’d be better off without the rest of Canada, there’s just a kind of narcissism, which is, ‘I’m not happy. I have to share therefore I would be better on my own’. Oh, yeah, tell me about it. Oh, you got oil. You (rest of Canada) got oceans. You’re worried, you’re frustrated. You can’t get it to market, but you don’t have a port. You think that being independent of Canada, which has three oceans, is going to help you get oil across the ocean? It’s ridiculous, but it’s about tearing down. It’s not about building up.”

Agree or not, Hamish Marshall says Alberta isn’t going anywhere yet.

“It’s when Block Alberta gets founded, that things are getting interesting.”

And that’s not impossible.

In an interview with your teacher Donna Kennedy-Glans, Reform Party founder Preston Manning argued that Quebec and Alberta are similar, stating, Quote, “Both want a more decentralized federation for somewhat different reasons. Quebec more for linguistic, cultural and social reasons, the west for economic reasons.”

Manning went on to say that if Canadian unity cannot be preserved through decentralization, the potential for separation should be taken seriously, not dismissed.

But unity, we often forget, is a two-way street.

Alberta has declared that the litmus test for confederation will be whether Canada builds a new pipeline from Alberta’s oil sands to tidewater on BC’s north coast.

The last time this pipeline route was explored – what was then known as Northern Gateway – opposition was fierce, across Canada, but particularly in BC and especially within numerous First Nations communities who hold unceeded title to the land the pipeline and tanker traffic would have to cross. And in the face of that opposition? The project died, feeding Alberta’s anger and resentment.

Will the outcome be different this time?

Well, remember the issues of Indigenous sovereignty we discussed earlier? Remember Canada’s legal duty to consult First Nations communities? As Conservative strategist Hamish Marshall tells us:

“It’s not just the duty to consult. In the Constitution, there’s obviously been a whole bunch of Supreme Court decisions around this as well – all of which say that there’s a duty to consult, but there is not a veto. But nobody really knows what that means and where that line is. The assumption has been – you almost have to give a veto.”

And while some First Nations certainly appear to support the pipeline proposal, others very much do not.

Then there is BC.

The provincial government is vocally opposed to the project as well and while the public supports the idea of helping Alberta export their oil, a majority of British Columbians want to be able to veto any project that doesn’t fully address environmental and cultural concerns associated with tankers travelling north coast waterways – especially since millions of taxpayer dollars have been spent conserving much of the region, known as the Great Bear Rainforest.

Saskatchewan’s premier Scott Moe has stated BC has no right to veto a pipeline. Constitutionally he’s right, the final decision rests with the federal government and, in all reality, the courts, should First Nations challenge a governmental decision.

But even if this is Canada’s coast, that doesn’t mean it’s not not BC’s coast.

Huh?

Well, British Columbians, like Albertans, are Canadians too. And BC, as our former prime minister Kim Campbell reminds us, has struggled with feelings of alienation as well.

“I’m from British Columbia. We’re the Rodney Dangerfield of Confederation, we don’t get respect.”

If we can’t all or even mostly agree on an issue this important to so many, who gets to have the final say? Has the prairie west had it worse for longer? Do they get to veto BC? Or should BC concerns be prioritized? What about the divides within the provinces? After all, no region is monolithic, nor are indigenous nations. Should coastal first nations have the final say, as a tanker spill would devastate their way of life, or should those nations who rely on oil and gas jobs be allowed to finally share in the prosperity pie, paving the way for economic reconciliation?

So, if BC or First Nation communities decide they don’t want to risk a tanker spill on the north coast, what should the federal government do?

Lawyer Peter Biro explains the true complexity of this dilemma.

“Regionalism, national identity, separatism of some kind – is not in any way inconsistent with or incompatible with a full and deep commitment to liberal constitutional values. The problem becomes when members of any community decide that the values of their community have to be either universally followed by others or universally respected and deferred to, and that becomes problematic in the public square.”

It does.

After all, too many in Canada have imposed their values and identity on Alberta, supporting decisions that have actively driven a wedge between Alberta and the rest of the nation. But Alberta sometimes fails to understand that other regions and peoples of Canada also have a unique identity, equally tied to land and specific cultural values. Would imposing a pipeline on (BC and) Indigenous communities be altogether different than the type of heavy-handed approach that has angered so many in Alberta? Would this not be trading one problem for another?

And maybe Alberta has had a raw deal for longer. Or maybe not. Maybe BC should give a little. Or maybe that’s impossible. Maybe Alberta should look elsewhere. Or maybe they can’t.

See? This is a messy situation.

“Oil is extremely important to people here in Alberta, and people in BC want to protect the ocean and all the wildlife that’s on the way from here to the ocean. That’s completely valid for them to feel that way. It’s kind of a no-win situation right now between Alberta and BC.”

And journalist Josh Hall should know – he was born in Vancouver and now lives in the exurban community of Red Deer, Alberta.

So, when it comes to forging a shared national identity? Josh says:

“I don’t have much hope that people can just come to the table and make a compromise.”

Which isn’t to say it’s impossible either.

The federal government believes it has found a fair compromise. In signing an agreement to support Alberta’s pipeline proposal to BC’s north coast – and get rid of a law essentially limiting oilsands emissions – the province will work with industry to advance a massive – and expensive – carbon capture project. Though this technology is unproven at this scale, the government is betting on the ingenuity of the same people who extracted oil from this impossible landscape in the first place.

But even if this bet is a good one, it won’t appease the opposition – who still fret about the climate, tanker spills and even the impact of earthquakes, tsunamis and landslides on the pipeline route. Environmentalists also worry these risks compound other Albertan decisions: coal mining in sensitive Rocky Mountain watersheds, open season on federally threatened species like wolverines, and the resumption of hunting transboundary grizzly bears.

And then there is the issue of Indigenous sovereignty, which also isn’t addressed in this grand bargain.

Succeeding as a country means having give-and-take conversations, obviously, but one region – one people – can’t give or take more than another. After all, failing to strike the right balance in the past is a major reason for the divisions we see today.

For this reason, even with an agreement in place, more work remains if we’re to unite all peoples and all regions in deciding on this or any path forward.

“Coming to some reconciliation of what that can look like, in a place like Alberta, I think is a lot of work. And it changes. And I think figuring out how to get people’s voices heard and understood on those kinds of things is an imperative. It’s our imperative. It’s what we have to learn to do better.”

Former Alberta cabinet minister Donna Kennedy-Glans is right. But as former prime minister Kim Campbell argues, this is a national challenge as well.

“Never trust any political leader who is appealing primarily to anger, because we all have buttons – we all do.”

Why reject grievance politics? Kim Campbell says:

“What frame of mind are you in? You’re not in a frame of mind to solve any problems. There are a lot of people who are in many different ways of life. And sometimes in government, you say you want to do something, and then you hear from people, ‘this is how it will affect us’. And you go, ‘Oh, I haven’t really thought about that, because your reality isn’t real to me’. I never realized it would have that effect. And that’s why you need people from all different places talking about what the effect will be.

The Alberta-born former BC Lieutenant Governor Janet Austin agrees.

“Try to understand what are the reasons people hold the views they hold. Sometimes it’s fear based, sometimes it’s based on their livelihood. We need to understand that. Sometimes it’s simply based on misinformation. But to try to get underneath and behind the reasons why we all hold the views we hold – it’s key.”

Janet adds:

“Try to understand their point of view and not enter into those discussions with an expectation that ‘I am going to prevail’, but with an expectation that ‘I will listen sincerely and with a willingness to be convinced if confronted with superior logic and argument’.”

That means, to forge a truly national identity, we need to be exposed to each other’s realities and, in the doing, we might find we have more in common than we think.

After all, what Alberta, Quebec and many rural communities in Canada fear losing – their culture and right to self-determination – is what many Indigenous communities have already lost.

Take the settler-sparked decline of the bison from millions of animals to mere hundreds – and the real consequence of cultural loss – says Indigenous leader, Dr. Leroy Little Bear.

Take the settler-sparked decline of the bison from millions of animals to mere hundreds – and the real consequence of cultural loss – says Indigenous leader, Dr. Leroy Little Bear.

“(The buffalo) has a whole bunch of cultural roles that it fulfills for our people because without it, I’m just a little bit less Blackfoot.”

Leroy puts that into context for us.

“Being a little bit less Blackfoot with (the buffalo’s) absence? It would be similar to Christians. In our modern world, for instance, we have sacred Christian places we go to. What if all of a sudden, the Vatican was no more, say? You could still have all the church beliefs, you could still have all the Christian beliefs, you could still practice them, but without that kind of iconic symbol out there, there’s something missing. If the churches were taken away, or all closed down, you could still have all the beliefs, but they’d be just a little bit less Christian.”

Thanks to Leory, that’s loss we can begin to understand. Now, think of everything we’ve discussed and start trading the names Little Fort for Valemount, Fort McKay for Fort McMurray, Saint-Jerome for Kanien keha ka and what you begin to see is that the fears, the anger, the needs, the wants aren’t that different between the communities, minus the seismic difference of history.

This could be – should be – a common starting point to build bridges between different cultural communities and forge a true national identity to help us move forward as a nation.

But according to a MacLean’s Magazine investigation, it’s not.

At least not yet. Why? Well, in times of crisis – in times of change – we worry there will only be so many resources available. We worry our rights and interests will be pitted against those of others.

After all, as lawyer Peter Biro explains:

“There is scarcity in the world of most things, but in a world of scarcity, you know that there’s going to be conflict.”

And according to Peter, that means we must remember this:

“We come to the world as owners of ourself. We externalize that equal moral personality by making claims on other things, title to land, ownership of an object, but we do that in a way that is respectful of the needs of others and the equal claims of others to those same resources.”

Respect is the key word.

We don’t always have to agree on everything, but we must learn to respect different – and often divergent – claims to the same resources and, yes, the same land.

We must recognize the validity of different histories, wrongs, and fears, while understanding that two truths can be real and valid at the same time, even if they stand in contrast to one another.

Will we do this? Will we genuinely respect our neighbours in this vast land? Or in the face of American threats and urgent challenges, will our different identities fracture national unity?

“If you’re going to come up with solutions, it means you have to really understand the detail and the complexity and the options. If you take one option off the table, what does that mean for something else?”

Author Donna Kennedy-Glans is right. Why? Ethicist Kerry Bowman offers an example.

“One of the things I’ve seen in Africa is, you know, people have said: ‘You cut down all your forest to make progress. Look at Europe; look at Britain. Britain used to be forested! Scotland was forested! Now you have nothing. And you’re telling us we can’t do this? That we’re not allowed? That this is wrong for us to (develop our natural resources)? You did it so that you can move forward. So, how can you say we can’t do it? Why can you do that (develop resources and have economic progress) and why should we do this (protect our landscape) when I’m living in a state of poverty?’ And I don’t have a good answer for that. I don’t. I’m struggling with these things.”

In other words, every decision has the potential to impact someone’s bottom line – their culture, their beliefs, their livelihood, their sense of justice, their – our – environment.

As pollster Shachi Kurl reminds us

“Every action has a reaction”

Exactly. And it’s why Peter Biro, a lawyer and the founder of the think tank Section 1, argues:

“Our differences don’t automatically make us stronger. That’s not the case at all. We need to become stronger in spite of our differences, and we can certainly become richer because of our differences. There’s no question. But differences, particularly demographic, cultural and ethnic differences, actually weaken the civic culture. Heterogeneous societies are more fragile than homogeneous societies. Homogenous societies are stronger. It doesn’t make them better. It just means that there’s an absence of all of the fault lines that exist in a heterogeneous society.

The fact that we are culturally and ethnically diverse, it’s not a good thing or a bad thing. We like to celebrate it as a good thing. I don’t view it that way. What I say is it’s a reality, and what we need to do is to learn how to manage it really, really well and make the very best of it and turn it into a win. But we should never be so smug as to believe that the fact of diversity makes us better or makes us stronger. We will see, as Europe is seeing now, what diversity does if you don’t get people of diverse communities on the same page on certain fundamental questions?”

Of course, it’s here our democratic system should save us. It’s what should allow us to recognize truth, respect difference, and find reasonable ways of reconciling majority will and minority rights. But that assumes, of course, we’re not divided on the value and validity of our democratic system.

“When you see divisions and we do on the fundamentals themselves, we have big challenges.”

If we can’t agree on the fundamentals of democracy, how will we ever come to a shared understanding of land, identity, and the correct path forward?

Simple: We won’t.

For this reason, Peter believes:

“I see a commitment to those fundamentals once you really understood them and understood what the stakes are as being an essential part of a national unity project, because those core fundamentals are universal. It is a way to get people who are committed to different kinds of political agendas in good faith on the same page on some very fundamental questions that shouldn’t divide them at all.”

Can we do this? Can we unite around democratic principles? Can we unite as a nation and solve our problems together?

“We’ve been talking about national unity for a very long time, and yet we’re still together.” – Heather Scoffield | Former Journalist and Economics Expert

“Canada is the second largest Federation in the world. It is very difficult for one region to pay close attention to what’s happening in another region when that region is 2000 miles away. It’s an enormous country. It’s understandable that the people of Ontario don’t know much about calf prices or the price of a barrel of oil. We don’t know much about auto manufacturing.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Member of Parliament

“We’re such a huge country that we are almost a collection of 12 countries, and yet our strength is being one country.” – Heather Scoffield | Former Journalist and Economics Expert

“There’s this perception that Canada has always struggled with identity. Who are we? What are we? Well, if you look at Canada as a political unity – say you start in 1867 and you go forward to when British Columbia joined and Manitoba become a province – so 1870s. It’s as old as Italy. It’s older than Germany as a political unit, and that surprises people. We’re not as old in terms of institutions and things that have been tried in multiple other ways, but as a political unit, we’re quite old and quite mature, and we’ve been quite successful. Our system has been adaptive and been able to keep us going. I think this is a tremendous time to be a Canadian.” – Harvey Locke | Biodivesity Expert

“We’ve been through some rough times, and I’ve watched Canada come out stronger on the other side of every single one of them, and not sucked into the depths of any of them, either. It means that we’re left with the social cohesion and the institutional integrity to soldier on and meet the next crisis.” – Heather Scoffield | Former Journalist and Economics Expert

“We’ve been through some rough times, and I’ve watched Canada come out stronger on the other side of every single one of them, and not sucked into the depths of any of them, either. It means that we’re left with the social cohesion and the institutional integrity to soldier on and meet the next crisis.” – Heather Scoffield | Former Journalist and Economics Expert

“We’ve woken up to the fact that we’re a country that was built by the French and English on Indigenous foundations. Those foundations remain. The French and English element remains, and then for the last 60 years, we’ve become a country the whole world has come to participate in. We’ve become this remarkable multi-ethnic, French, English, Indigenous presence factor. All of that can help shape what the future is. The reconciliation, living with difference, imagining diversity of strength, that’s exactly what the challenge of the 21st Century is. And we’re ahead of the curve of every other country in the world on that. I have no doubt about it. It’s an informed opinion.

We’ve got to accept that our challenges, which feel difficult, are opportunities for us to be a leader of the pack and for us to actually model the behavior that we say we value. I think we can.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

We must.

“It can always be better and to and to paint a vision that doesn’t leave things out. It’s very easy to just talk about the economy, but I think that is so narrow, so one dimensional. It’s important to think about all aspects of life and make sure that it’s not only about your life that you’re thinking about. It’s about people that may not have it as good as you, people that are in completely different circumstances.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Member of Parliament

“It means difficult conversations, and it means give and take, and that’s not always going to be pretty.” – Heather Scoffield | Former Journalist and Economics Expert

“If humans try to crystallize themselves at one scale, for example, I’m an Albertan, or I am a German, or I am a whatever, and then that becomes a unit that is in conflict with everything that isn’t that. You limit yourself and you condemn us all. So how about we rise above that and recognize that I’m a human at every scale, from my immediate family to my town to my province to my country to the world as a whole. And boy, do I ever feel lucky to have such a big playing field?” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“That comes a lot closer to a vision that people can appreciate and rally around than just one that points to half a dozen problems that are burning right now.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Member of Parliament

“Our responsibilities – yes, they’re to us, but they’re to future generations.” – Pete Smith | Artist and Rural Advocate

Truly.

That means it is our responsibility – each of our responsibilities – to learn about and respect our neighbours, and to work with each other to find the better answers we’ve all overlooked. Only then will we uncover our true Canadian identity and find our way forward.

“My advice would be to think broadly.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Member of Parliament

“Because Canada is the best country in the world, hands down. Hands down! And yes, there are issues within families, if you will, but the unit that is Canada, in my judgment, is a wildly successful country” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“We need to travel as a country and as a people.” – Heather Scoffield | Former Journalist and Economics Expert

“Meet people. Understand the challenges that they face across this big country. Because, as we talked about before, it’s very hard to appreciate the problems of Nova Scotia when you live in in Foremost, Alberta. So getting out and meeting people across the country helps a tremendous amount.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Member of Parliament

“We need to learn to listen.” – Heather Scoffield | Former Journalist and Economics Expert

“So many people just – they don’t want to hear it. They don’t have the energy or the effort to have their minds changed. They don’t want it to be changed. So they don’t listen, and that’s what you have to do. You have to listen.” – Josh Hall | Journalist

“It’s easy to get along with those you agree with. The difficult thing is to get along with those that you don’t. And in the community I live in, we need to do both, and I think we have to do better in that arena.” – Pete Smith | Artist and Rural Advocate

“That’s good. We should talk with each other. We should be able to analyze the information we’re getting from social media and understand what’s wrong.” – Dr. Kate Moran | Scientist

“Look outside of your high school. Keep doing what you’re doing, but definitely reach out to somebody else in the world who might have a different opinion than you, whether they’re a province away or in the same class as you. So many people are so set in their ways and their opinions they literally don’t take any time whatsoever to ask questions of the other side and why the other side feels the way that they do. Open mindedness is what it needs to be.” – Josh Hall | Journalist

“Curiosity is a pretty amazing thing. When you start asking questions of folks who don’t agree with you, you find out, most of the time, that they have the beliefs they have because they’ve either been hurt, something really tough has happened in their lives. They’re looking for solutions. They’re looking for meaning. If we can get to the humanity of each of us, we can have some empathy and some a sense of understanding.” – Ilona Dougherty | Youth Advocate

“If we don’t walk into a room and immediately judge, that helps. There’s a way to carry ourselves, and I think it comes from the heart. Too often we end up getting relegated into React, React, React, and then from there, that becomes the default. That becomes the action – in fact, becomes reaction.

Can we as a group figure out how to act collectively and just love? Extend that love is the one resource that you can just use as much as you got, as much there as you can possibly manufacture or create.” – Pete Smith | Artist and Rural Advocate

“When you sit down and talk to people, often the values overlap 80%. There’s just so much that we have in common. That’s what we need to concentrate on.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Member of Parliament

“Everything in life that is good, whether it’s charitable and social purpose, whether it’s building a business, whether it’s who runs our government, or even people that inhabit a neighborhood together, is based on people.

Being able to work with people, understand people, and sometimes manage people and sometimes come to compromises with people and have civil discussions. That’s the most important skill compared to almost anything else.” – Randall Howard | Angel Investor

“You can be the best basketball player in the world. You could be the smartest person in the world. You could be the best in any field out there. But if you don’t know how to get along with people, you’ll never get anywhere. That’s where this notion of problems that we have in our society, about racism, bullying – all those people type issues – is because people don’t know how to get along with each other.

The best skill a person can have – the best skill students can have – is knowing how to get along with people, and that will easily extend knowing how to get along with that buffalo.

What do you think?

Terms & Concepts

Referenced Resources

* Quotes have been edited for brevity and clarity.