Estimated Read Time: 22 minutes

Does Nature Need Half?

Decision time.

What should we do? How would you balance people and nature – how would you safeguard biodiversity while bridging the urban-rural divide, growing our economy, meaningfully achieving reconciliation and overcoming divisive cultural wars?

Look, picking sides is easy. Knowing whose right and whose wrong is easy. But making the call? Living with the consequences? That’s hard.

We might not live in the society we want to live in.

We might not have the leaders we want – in politics, in business, in advocacy, in the media.

We might not like the facts we’re told – or how the facts are presented.

And yet today? This is what we have.

We can change it, but change takes time. And the question isn’t what we’ll do tomorrow, but what can we do today?

After all, the issues are too urgent and too real to wait until tomorrow. We need to make a decision today – for people and for nature.

How to make a decision? Well, consider this: In Canada, we often assume that the most pressing decision we face as a nation centres on fossil fuels. How or if we develop them. How or if we transport them. How or if we’ll move on from them.

And yet if biodiversity is the most pressing environmental issue facing the world – and many argue it is – and if biodiversity is the issue that Canada is best able to impact in a major way – and many argue it is – there might be a more pressing decision that needs to be made: How best to manage our vast forests.

You might remember this bit of real talk from the UN’s former Deputy Executive Secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity, David Cooper:

“Look at Canada: we have this vast boreal forest. We need actually to maintain practically all of that boreal forest and maintain it as boreal forest, whether or not it’s a formal protected area if we’re going to maintain the life support systems of the planet.”

Now here’s the context of David’s quote:

“That doesn’t mean that the entirety of the Canadian boreal forest will end up being a protected area, but it does mean that it should remain essentially as a forest ecosystem.”

What does that mean? David explains.

“If you want to, for instance, have a forestry industry, then you’re going to continue to maintain the forest. There are many forestry operations that can have low impact on biodiversity. Of course, avoiding logging of primary forests is a priority also for maintaining biodiversity.”

Cyril Kormos agrees but believes David’s burying the lead.

“You can’t solve either crisis [climate or biodiversity] without saving primary forests or old-growth forests.”

Cyril is the founder of the founder of Wild Heritage and is one of the world’s leading researchers on primary forests.

“The importance of these forests is that not only do they contain, globally, over two-thirds of all species on land, but they also store huge amounts of carbon.”

What Cyril uncovered?

“Of the planet’s original forest cover that remains, less than a third is old-growth forest, and that’s dwindling by millions of hectares every year.”

And that’s a big deal, Cyril says.

“It’ll take centuries to recreate what’s been lost. You don’t recreate an old-growth forest quickly.”

Why? Cyril explains that “forests evolve over thousands of years, and they create their own conditions. They create their own microclimate. They create their own biodiversity. They create their own soils. They create their own temperature. They’ve manufactured these very special conditions under which they can maximize ecosystem services. They store the most carbon. They produce the cleanest freshwater. They regulate the water flows.”

Indeed, Cyril believes that the fate of our biodiversity and our climate has less to do with the oil sands or a cow’s rear end and much more to do with how we manage our forests.

“You know, industrial use is simply not compatible with maintaining old-growth values.”

Cyril adds that even though this is a major issue, it’s not being addressed properly, in part, because forest conservation is and even tougher issue to tackle than fossil fuels.

“Forests are always the tricky, difficult issue.”

That’s in part because of the value of forests to national economies – including Canada’s. And it’s why Forests Ontario doesn’t think Cyril is seeing the, um, forest for the trees.

They tell us, “according to Natural Resources Canada’s ‘State of Canada’s forests’ report, the forest industry contributed $24.6 billion [1.6%] to Canada’s gross domestic product. The forestry industry also directly employed 209,940 people in 2017. Forests Ontario’s 50 Million Tree Program supports more than 300 full-time seasonal forestry jobs and generates a total GDP impact of over $12.6 million per year.”

Forests Ontario is an industry-sponsored not-for-profit that seeks to champion forestry and forest renewal, helping lead that province’s tree planting efforts. They told us by email that Canada has enough forest – if managed thoughtfully – to support both people and nature.

“Canada’s forest cover represents 30 per cent of the world’s boreal forest cover and ten per cent of the world’s overall forest cover. There are 347 million hectares of forest in Canada – that’s 35 per cent of our country’s land mass.”

But Cyril believes those statistics are misleading.

“It’s a little bit like the oceans. You think that our forests are infinite, but they’re not. And it’s a variety of different threats, death by a thousand cuts.”

Cyril tells us that when it comes to deciding the future of the boreal – or most forests – it’s primary forests that matter.

“Think about the boreal – less than a third of it is old-growth forest.”

Yet, as Forests Ontario points out, “forests and trees will eventually burn or otherwise die, and their carbon stores will return to the atmosphere. Forestry can ensure that we always have healthy, growing forests that actively sequester and store carbon.”

Emphasis on the growing, as organizations like Forests Ontario, are continuously planting trees by the hundreds of millions each year.

But Cyril says this ignores the time it takes for old-growth forests to regenerate, the importance of primary forests, and the science of how forests work.

“You can plant more trees, but it doesn’t give you what you need. What the science is telling us, in fact, is that if a forest is resilient and left alone, it’ll bounce back [after a fire or infestation] and will be even healthier as a result. If we interfere and manage the forest, we’re preventing the forest from actually developing its own resilience and its own capacity to deal with threats.”

Cyril adds, “it seems like whenever there’s a problem with a forest, the solution from the forest industry always somehow seems to end up being a chainsaw.”

And to that, Forests Ontario takes exception.

“Regions where we actively combat natural disturbances, we still need to maintain an appropriate level of disturbance in order to mimic natural conditions. To arbitrarily eliminate one strategy that has been scientifically proven to have important applications would be inappropriate. Any active operations require years of planning before they are implemented. It never starts with a chainsaw!”

Forests Ontario adds: “Canada has some of the best sustainable forest management practices in the world. Less than 0.5 per cent of Ontario’s provincial forests on Crown land are harvested each year, and 100 per cent of harvested forest must be successfully regenerated [by law].”

And Cyril’s response?

“If all this stuff were truly sustainable, and if it were truly a balanced approach, we wouldn’t be talking about the problem with the caribou, or the problems other endangered species, or that less than a third is old-growth.”

Danijela Puric-Mladenovic is a forestry professor at the University of Toronto, and she’s studied this debate closely.

She tells us that to understand this issue better, we must understand our history. At one time, Europe was heavily forested, like Canada, but that changed, and the loss of European forests drove settlers to our shores.

“Canada is a relatively new country and people 200 years ago, they came because it’s a promised land. But we still have a first settler’s mentality. For the time – 200 years ago, 100 years ago – yeah, people didn’t know any better because we didn’t have that knowledge. We didn’t have as many environmental issues, or we were not aware of them as we are now. But keeping the first settler’s mentality in the 21st Century when you have invasive species, [and] climate change to produce, let’s say, toilet paper? You don’t need to cut your natural forests to produce toilet paper. There are other means.”

But if we limit the logging industry, won’t that impact our economy? Cyril says, “the question is, do we need to be sacrificing old-growth to meet those needs? I think the answer is most likely no.”

But if we limit the logging industry, won’t that impact our economy? Cyril says, “the question is, do we need to be sacrificing old-growth to meet those needs? I think the answer is most likely no.”

Cyril, like Danijela, believes we can protect our primary forests and still have a robust forest industry.

“We can get our wood from other places instead of continuing to log old-growth forests. You switch to plantations, you switch to areas that are already degraded – places where you can’t get the old-growth forest back. You use those places for manufacturing your timber.”

But Forests Ontario doesn’t think we need to partition how and where we use our forests, adding, “Canada has approximately 10% of the world’s forests but almost 40% of the world’s certified forests [meaning they meet the standards of internationally recognized, third-party standards].”

But Forests Ontario doesn’t think we need to partition how and where we use our forests, adding, “Canada has approximately 10% of the world’s forests but almost 40% of the world’s certified forests [meaning they meet the standards of internationally recognized, third-party standards].”

Cyril doesn’t dispute that Canada is in better shape than some countries, but he believes we’re still not doing enough – given we have a global reservoir of primary forests.

“Sometimes there’s a common-sense compromise, and sometimes you got to make a hard choice.”

The BC government, as it turns out, doesn’t disagree with that message.

As long-serving BC cabinet minister Mike Farnworth explained to us, his government attempted to significantly change the province’s forestry practices, scaling back old-growth or primary forest logging to help the climate and biodiversity, especially species-at-risk, like the caribou.

But, depending on the source, the decision will cost the province possibly 4,500 jobs.

In a region of many millions, that might not seem like a massive number…unless it’s your job that has been lost; or your community that will disproportionately suffer the consequences of job losses.

Joel McKay, rural advocate and CEO of Northern Development, tells us, “what’s needed…is a society in which every Canadian can succeed…that means access to proper education, healthcare, social services, a job market with robust opportunities.”

But Joel says, “these things can only exist in rural areas if we have a landscape that’s attractive to business development and investment, which generates the needed tax revenue to support the social services that support healthy development of our children into adults. That means we need an environment that supports resource extraction, attracts investment and leverages the benefits generated from that to reinvest in rural areas so that they have just as much opportunity as our urban areas.”

And when governments make decisions to prohibit resource development – like BC’s efforts to reduce logging in primary forests – Joel believes it deepens the urban-rural divide and highlights how little power rural communities have in electoral politics.

“Rural BC has very little to say where it concerns provincial elections, much less than federal ones. Unlike other jurisdictions, Canada does not have a proportionate electoral system, business environment or taxation regime that recognizes the outside value rural areas generate for the rest of the country.”

Political Science professor Dr. Will Greaves agrees Canada’s electoral system isn’t proportional but says that’s to the benefit of rural communities and their advocates.

“Actors who are, maybe, relatively minor within our system can still be veto players. Under the right circumstances, the mayor of Montreal or the mayor of Vancouver, or the premier of one province or another, or as has been the case in Canadian history, even a single legislator in a single provincial legislature, can have the power to fundamentally alter the course of the country’s history.”

And social scientist Dr. Victoria Lukasik says that her research on environmental policy suggests it’s actually rural communities that have the most power in our electoral system.

“Especially in Western Canada, our vote is really affected by the rural population more so than the urban population.”

Who’s right? Well, in truth, they all are.

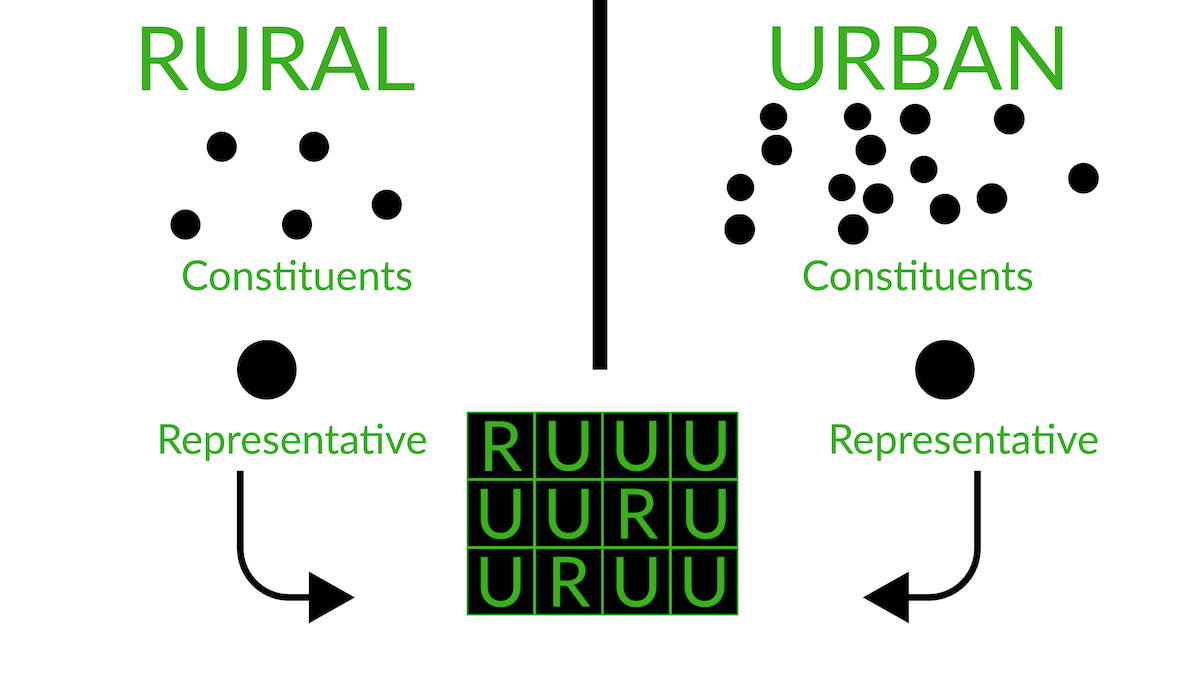

Rural communities have less of a say in provincial and national matters than those who live in urban centres because urbanites are the significantly larger demographic in Canada – they represent more than 80% of the Canadian population. Yet urbanites are significantly underrepresented in Canada’s first-part-the-post electoral system.

As Michael Pal of the University of Ottawa explained to CBC Radio, “your vote in Labrador is probably worth three and a half times more than a vote in Vancouver. So, it’s as if we said everybody in Labrador gets three and a half ballots, and everybody in Vancouver gets one.”

And there are countless examples of urban ridings with populations in the hundreds of thousands and rural ridings with populations in the tens of thousands.

Michael Pal added to CBC, quote, “The least powerful voter in Canada is probably a recent immigrant from Pakistan, Bangladesh, India or China, who lives in Brampton, Markham or Mississauga – places where population is growing very quickly. So that tends to be the suburbs around the biggest cities. So, it’s not necessarily downtown Toronto, but it’s the 905 area code [the suburbs around Toronto].”

In our system, it’s easier for specific issues in rural ridings to be addressed. Think about it:

Rural constituents have fewer voices to battle to get the attention of their elected representative. And given that a rural representative has fewer constituents and fewer issues to juggle, they, in turn, can be effective advocates in government or opposition.

It’s why strong opposition to a park proposal in one rural riding can kill the planned park outright. After all, park proposals in one part of the country are rarely the top issue for a majority of voters in enough urban ridings to counter the focused, political advocate for the one riding where opposition is strongest.

Make sense? Good. Here’s the flip side.

Broad, less-specific policies – like, say, a carbon tax or regulations that limit primary forest logging – usually can succeed in the face of rural opposition, even if the urban vote is more diluted.

In this case, a broad policy might be the top issue for enough voters in enough urban ridings. And if way more people in way more ridings contact their representatives about one policy, then the urban representatives will be united on the issue. And given that there are more urban ridings than rural ridings, a majority of urban elected representatives can overrule the majority of rural representatives.

It’s an imperfect system without a perfect alternative, especially when the goal is to balance majority will and minority rights – and minority rights of one segment of the population against the rights of other minority populations.

And almost every decision impacts someone’s bottom line – their culture, their beliefs, their livelihood, their sense of justice, and their – our – environment.

And it’s why governments can be accused of going too far or not far enough, all at the same time, when tackling an issue like primary forests.

Yet the middle-of-the-road compromise only means one outcome for nature, according to forest advocate Cyril Kormos: “Usually what ends up happening is that the environment loses.”

And compromises also aren’t helping economic growth, business leader Hal Kvisle argues.

“I have no objection to us meeting the highest environmental standards and every job we do, doing it right. What a lot of us are objecting to these days is the grinding regulatory process that we have to go through before we can even begin the project.”

Hal is the former CEO of Trans-Canada Pipelines and is one of the strongest voices for business in Canada.

“Even in [resource-rich] Alberta, people don’t really understand the benefits of the resource industry.”

“It’s easy to say that the royalties that the oil companies pay go into provincial coffers and pay for schools and hospitals and things like that. But that’s only the tip of the iceberg.”

Hal says, “the real benefit is in the high-quality employment that people do. And then, of course, the very significant income taxes that those individuals pay. So, it’s really much more the money that flows through the employees towards the Government of Canada. That’s a much bigger fish.”

But Hal believes that economic impact is threatened when compromises ask “companies to spend $800 million to get through a regulatory process and then go out and build the pipeline in exactly the same way as if they had never been subjected to that regulatory process.”

It’s why Hal argues we need to make smarter decisions for business – like fewer regulations and higher fines – and smarter decisions for nature.

“We need to be careful that as we try to compete with other parts of the world in the forestry industry, we don’t open it up to just willy-nilly clear-cut logging.”

But that decision – any decision – should be left to the communities, says Shianne McKay of the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources. She says we need to “hope that it’s the best decision possible given their circumstances. [But] you can’t really address the environmental issues in the face of poverty. You have to address both.”

Jim Bottomley – a futurist of Indigenous descent – agrees with Shianne.

“Rural communities have had a tough time.”

But according to Jim, sometimes the local context doesn’t allow us to see the bigger picture – sometimes community needs can blind us to global realities.

“No matter what values drive us, we need to be aware of these needs, and each of these needs are often blind spots.”

And that all seems contradictory and makes finding a solution seem overwhelming. It’s why former Alberta cabinet minister Donna Kennedy-Glans argues: “we risk a lot if we stay in this space in Canada. We like victims, and we like to be heroes. But I don’t think we have much more time for it. There are victims in this world, but I think we’ve created way more than there really are.”

Agree or not, against that backdrop – in a world where it’s easy to offend and hard to build alliances across divides – most of us simply shut off rather than engage. Or, as Dr. Aleem Bharwani tells us.

“So, Hasan Minhaj, one of the online comedians in the US, has this line where he says, ‘I’m more lazy than I am woke’. And I think that’s true for many of us.”

Aleem is the director of public policy at the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, and he understands that the issues are challenging – that what to do isn’t easy or obvious. But Aleem adds, “It’s true of personal relationships, it’s true of big system issues, it’s true of a lot of things: We do always realize what we’ve got until it until it’s gone.”

It’s why Aleem believes we all need to overcome our fear – and laziness – to help find solutions to this question and all challenges we face. But in the doing, we must remember:

“There is no point in policy, even if it’s exactly what people want, if it’s not true, if it’s grounded in reality. Otherwise, it’s no different than a wishing well.”

Aleem says that means “the goal should be to facilitate honest, respectful dialogue.”

Which is easier said than done until you think about this Aleem argues:

“Sometimes you just need a turn of the kaleidoscope, where you’re looking at that same problem, that same piece of that same wall, and if some components are turned a slight way, now suddenly you can drive that line of inquiry in a very different direction.”

So, let’s do just that.

By now, you understand why the intersection of people and nature is so accident prone – so messy for decision-makers. And yet that’s in part because the decision-making axis has always been trees versus jobs, environment versus the economy, as Dr. Victoria Lukasik reminds us.

“Our economic interests, which are usually the same as our political interests, are things that are often in contrast with what is best for wildlife and our environment. It’s not to say that it has to be environment versus jobs – there are other ways – but that’s the way we kind of operate as a society in Canada.”

But what if we turn the kaleidoscope? What if we looked at the issue from a different perspective?

“I do think that there’s a lot of species that can survive [without parks]. Maybe it’s not the ideal, but they can survive in these modified landscapes that we’ve created.”

Victoria is a scientist who has worked with communities and decision-makers to better understand what it will take to save biodiversity. And Victoria says emerging science suggests parks are only necessary because we refuse to coexist with large carnivores.

“The large carnivores, we think of them as sort of being in need of pristine wilderness. And I think we’re more and more seeing that, actually, what they need is just for people to tolerate them.”

Grizzly bear biologist Gordon Stenhouse has been one of the leading researchers on this very subject. Gordon tells us, “our long-term data and published research papers allowed the government and industry to agree with the need for open road density thresholds for these [developed] habitats in order to ensure high levels of grizzly bear survival.”

Grizzly bear biologist Gordon Stenhouse has been one of the leading researchers on this very subject. Gordon tells us, “our long-term data and published research papers allowed the government and industry to agree with the need for open road density thresholds for these [developed] habitats in order to ensure high levels of grizzly bear survival.”

What does that mean? Roads – and the activities that usually go along with them, like ATV use, hunting, biking, and hiking – are more problematic for grizzlies than habitat loss.“And so that does sometimes require sacrifice on our part,” explains Victoria Lukasik.

It also means we face a choice.

Victoria says, “if the people on the landscape could make the space for wildlife, then we wouldn’t need to have a ton of parks.”

Famed bear biologist Dr. Stephen Herrero agrees, adding the biggest threat to grizzlies is?

“It’s really the lack of people willing to coexist. In order to coexist with grizzlies, you need to be willing to accept a certain set of behavioural standards. Garbage, [a] simple thing. But managing garbage, and storing it in a way that won’t attract grizzlies, is essential [for their survival].”

It’s why Humane Canada’s Barbara Cartwright says coexistence matters more than parks, more important than ideas like Nature Needs Half.

“On one side, we’re impacting our environment too much. So, can we have some space for the rest of the world to live without our influence? But then, if we do that, we’re going to lose our ability to live together and to maintain the health of the ecosystem with us in it.”

Northern Development’s Joel McKay agrees that we need to find a way to help nature while still allowing the opportunity for people to earn a living on the landscape.

Joel tells us, “you always want to pursue a balance between local economic needs and local environmental needs.”

But Joel reminds us that what “needs to be realized is that rural communities, especially those in the North, have few realistic options for private-sector employment that are outside of natural resource industries.”

Joel adds: “The question we need to answer is how do we right-size these industries so that they’re sustainable over the long term and operate them in a way that has little to no impact on the environment but still generates a healthy profit margin?”

Dr. Shelly Alexander is one of Canada’s leading experts on wildlife coexistence, and she believes: “coexistence is possible.”

Dr. Shelly Alexander is one of Canada’s leading experts on wildlife coexistence, and she believes: “coexistence is possible.”

Shelley’s work with canids around the globe – and specifically with coyotes in urban and suburban Calgary – have underscored this point.

“In most environments, if people manage themselves, carnivores mind their own business, and do their own thing and the conflict will not arise. That means there are options on a daily basis, if you’re living in an urban environment, to think about maintaining biodiversity, to coexist with carnivores.”

That said, even though Shelley knows we’re capable of coexistence, she doesn’t believe enough of us are actually willing to coexist with carnivores.

“There are people who are [saying] just forget this whole save half world thing. Just make it all about coexisting, humans and animals. But there’s limits to that. It’s not like we’re never going to run into conflict without something going wrong.”

Which is why Shelley believes only concepts like Nature Needs Half – the proposal to protect half the world – will ultimately save biodiversity.

“I am still an advocate for maintaining big, protected areas where, to the best of their ability, these animals can still live out their lives.”

But what if in exchange for more parks – having a policy like Nature Needs Half – we would also need to prioritize cultural and recreation traditions within them – including hunting, ATV use, skiing and wildlife photography? Neil Fletcher of the BC Wildlife Federation says the only good solutions are the ones that take into account rural culture and values.

“These people are here to stay. They’re not going anywhere. They’re going to be living on this landscape with you and the earlier you can get towards working with them and understanding their positions, the better you might be able to find some shared solutions.”

And that’s why Ken Wu – founder of Endangered Ecosystem Alliance – believes this is exactly the kind of trade we need to be willing to make.

“You can’t make an alliance with everybody, but it’s just that we can make alliances way beyond where we are now. Why? Environmental activists are good at rallying up other environmental activists.”

Which is fair, Ken says.

“You know, you talk to your own kind. You don’t normally try to do something uncomfortable all the time out with people who are not like you. That’s just not a natural instinct, right? But we’re gonna lose if we keep on doing this.”

Think about it: What if the choice isn’t environment or the economy, but culture or the economy? Animal rights or ecosystem rights?

How might existing alliances devolve and form?

How might voting blocs shift?

How might the conversation be altered?

Of course, there would still be division and disagreement, but maybe not down the same fault lines.

And if every debate didn’t send our traditional, national solitudes to their traditional corners for a pitted culture war – Indigenous values versus non-Indigenous values, pro-environment versus pro-economy, urban versus rural, east versus west – what might that mean?

It could be the spark needed for old adversaries to build new alliances, reshaping our debates and bridging our divides in the process.

Right now, our decision-making paradigm is predicated on having our cake and eating it too. But that seems like an old-world model; it seems naïve to think the good old-fashioned Canadian compromise can still yield enough win-wins for enough of us.

By choosing between a) way more resource development than we’re currently allowing, way fewer parks and very few recreational opportunities, such as hunting, skiing, hiking, photography and ATV use; or b) way fewer regulations, allowing for way, way more hunting, skiing, hiking, photography and ATV use opportunities, but also vastly increasing the amount of protected land and significantly scaling back resource development, we’d all be forced to reassess our priorities and understand what truly matters the most, to each of us.

We’d be forced to re-look at the policy proposals, economics, science, research, and stories of all affected to see what scenario best balances the needs of people and nature.

Which isn’t to say this is how we should solve our problems – that decisions are this simplistic.

They’re not.

But we do need to re-examine the problems we’re facing and how we make decisions. We can’t live in a world of zero-sum wins that cost more than dollars or species but also the very health of our democracy.

We need to think critically, act creatively, and simply do better – in our conversations, negotiations, and decisions – for people and nature.

In the words of our former prime minister, Kim Campbell, “create, as much as possible, bridges with people who may not think alike. Try and find ways of building around dogmatism and political polarization by finding the common ground. And it’s hard.”

For the sake of our democracy, we must consider those we disagree with when we decide what we must have and what we only wish we could have. Because, after all, as Shelley Alexander reminds us: “it comes down again to values what do we want? What’s the legacy?”

What do you think?

Task

Terms & Concepts

Referenced Resources

* Quotes have been edited for brevity and clarity.