Estimated Read Time: 19 minutes 30 seconds

Does one individual matter?

This class isn’t just theory; it’s not abstract.

This class is the foundation for understanding real issues in the real world – issues that affect you and me, today and tomorrow.

How so?

Well, for starters, it’s the first step towards understanding what it will take to truly balance the needs of people and nature.

Does that matter?

This challenge is as pressing as it is interwoven with other issues we face – problems like economic insecurity, social justice and democratic health.

By finding a better balance between people and nature, we can create a ripple effect of understanding and the possibility to tackle other, at times, more divisive issues in our society.

Maybe you think: This isn’t a hard challenge – the solutions are obvious.

Yet nothing is as easy as we assume it should be, in part because even when we think problems are black and white – good versus evil – they rarely are. Almost every issue is maddeningly complex, made all the more difficult when emotions like uncertainty, anger, hopelessness and fear are added to the mix.

And about now, you might think, well, none of this is actually my problem. And it probably shouldn’t be. But it is.

You see, not only are decisions being made today that will directly affect your future, right now, you are also entering your years of peak creativity.

As Ilona Dougherty argues, “young people from 15 to 25 are at the height of their lifetime ability to be creative, to be innovative. All these incredible abilities peak during that time of life, and they have the full intellectual capacity of adults. We underestimate young people all the time, and we need to stop doing it.”

Ilona knows better than most. She co-founded Apathy is Boring as a student and is the co-creator of the Youth & Innovation Project at the University of Waterloo. Her ground-breaking research has proven that your ideas, with help and refinement, are the very ideas that can help us create that better balance – that better tomorrow.

Ilona knows better than most. She co-founded Apathy is Boring as a student and is the co-creator of the Youth & Innovation Project at the University of Waterloo. Her ground-breaking research has proven that your ideas, with help and refinement, are the very ideas that can help us create that better balance – that better tomorrow.

“The research is very clear,” Ilona says. “For young people to grow up to be healthy, engaged adults, it’s all about having a sense of purpose and having an opportunity to make [an] impact.”

In other words, you might feel that you’re just one student without the power or influence to determine how late you can stay out on the weekend, let alone solve the world’s problems, but the reality is quite different.

As Ilona explains, “The only way to be a change maker is to be a change maker while you’re young.”

That’s right: You’re powerful because of your age. You can solve any problem we face because of your creativity.

“Young people have unique abilities while they’re young that society needs.”

Exactly, Ilona. And we all need your creativity. Right, Dr. Aleem Bharwani?

“Our most influential and impactful ideas will come from young people today who are growing up in this world.”

Adults – leaders – are so immersed in the problems we face they often can’t see the forest for the trees.

We need you to take a new look at old, if worsening, problems to see if there is something everyone else has missed. We need you to understand how hard truths collide and find ways to do better by different peoples and different communities – do better for more people and for nature.

Because we can all agree that we need to do better.

Discuss

Good points, but let’s get really specific.

Scientists have analyzed Earth’s record keeping system – fossils – to understand how often natural selection creates natural die-out – what’s known as the Background Extinction Rate. And though no one is certain – fossil records aren’t quite the Wayback Machine – most believe one species goes extinct per Million Species Years.

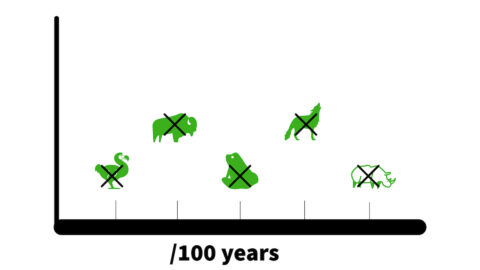

Our current extinction rate, depending on what mathematical equation you believe and use, is ten to 10,000 times higher than the planet’s Extinction Background Rate – the ‘natural’ natural selection, if you will.

Which is a big spread, but consider this:

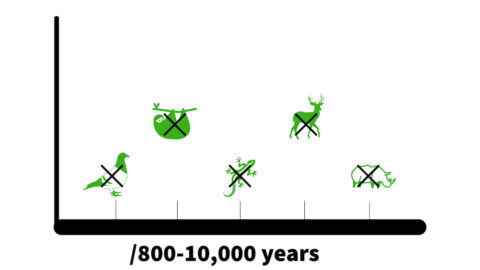

Of the species that have been known to exist and disappeared during the last century, their loss should have taken 800-to-10,000 years to occur. Not the 100 years it actually took.

And that’s according to a study that used a “conservative background rate of two extinctions per million species-years.”

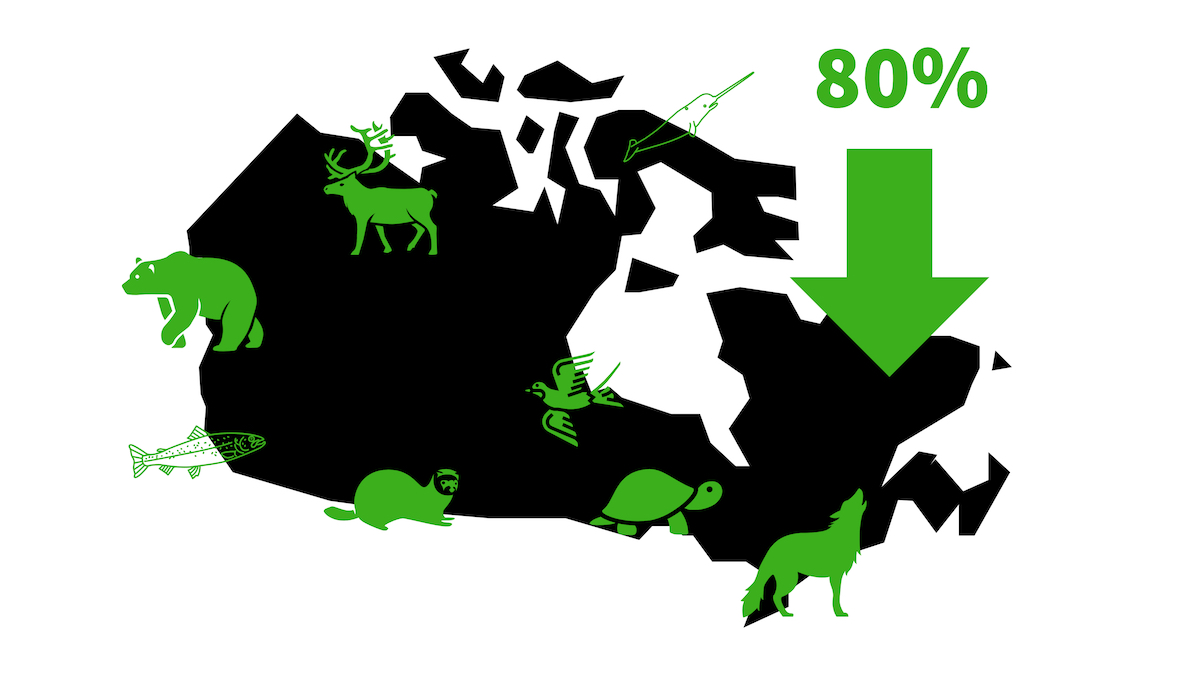

Globally, nearly 70% of every monitored species is either decreasing in population or range or both.

In Canada, a recent, comprehensive report that combines data from every level of government suggests that of the 50,500+ species we monitor, 1 in 5 are facing at least some risk of being lost and for 2,000 of those species, they’re at high risk of disappearing from Canada’s landscape.

Those are big, worrying numbers – and the problem is increasing. Fast.

How fast?

Well, according to the World Wildlife Fund, the largest environmental organization in the country, their research suggests that the average populations of threatened species in Canada have declined by almost 60% – with some data suggesting that for half of those species in decline, they’ve lost more than 80% of their population numbers in just 50 years. It’s a major reason why more than 500 species are legally listed as being at risk of extinction by the federal government.

For all of these reasons, some have concluded that we’re entering a period of mass extinction – a cycle where roughly three-quarters of all species disappear in a span of a few million years. There have been five in history – of course, the most famous being the one that whacked the dinosaurs.

Scientists tell us that if we’re entering a sixth mass extinction, unlike past extinction events, this one is human-caused. But that is, of course, a debate and, frankly, not a particularly helpful one.

Why?

Because the why distracts from the real issue: Unnatural natural selection at a rate well above the Background Extinction Rate means only one thing: Biodiversity loss.

“The bad news is that in most parts of the world, it is declining, and it’s declining at all levels.”

David Cooper was the Deputy Executive Secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity – a United Nations body that works to coordinate global efforts to protect biodiversity.

“Life on Earth in the broadest sense depends on biodiversity and the ecosystems that biodiversity makes up.”

And it’s not like there’s just one issue driving the global – or national – biodiversity decline.

Habitat loss. Pollution. A changing climate. The exploitation of wildlife. Invasive species. All of these are massive problems, and each issue is connected to the others, making solutions even harder to come by.

As David tells us, “there’s no single answer, so I would say: be wary of simple solutions to these complex problems.”

Indeed, protecting biodiversity will be hard work and will require creativity. But David explains there is good news.

“People are more likely to take actions if they see other people also taking actions.”

Of course, finding where to start is hard, but when we do start – such as our efforts to curb the exploitation of wildlife – we make a difference.

But in North America, the issue of exploitation of wildlife is a hard one to tackle, partly because we can’t agree on whether wildlife exploitation is or isn’t an issue.

Why’s that?

Well, for starters, many believe that well-regulated wildlife hunting actually helps enhance biodiversity, helping keep key prey and predator populations in check and in balance.

Others believe that managing wildlife populations is oxymoronic – that inherently you can’t manage something wild and that trying to do so harms our biodiversity.

What does the science say? Well, it’s divided! And it’s divided because of the value scientists assign individual animals.

Huh?

Scientist Dr. Victoria Lukasik says to understand this problem, first you must understand the tried-and-true scientific process.

“Scientific training usually tries to get all the personal stuff out of you. You’re supposed to be objective. You’re supposed to think of things in terms of numbers.”

Indeed, numbers matter in science, adds mathematical ecologist Andria Dawson.

“We’re always asking questions like, how are these two things different? Are they different? Are they the same? How are they different? Does X cause Y? And the way that we address those questions is using mathematics.”

Here’s the thing about math: As your favourite numerical teacher will tell you, it’s not a game of horseshoes. Being close doesn’t matter; getting the equation perfect does. That can be challenging when trying to understand human impact on wildlife, argues Dr. Victoria Lukasik.

“As humans, and especially as biologists, we like to put things into little boxes and categories. And nature isn’t quite so cooperative or so neat.”

And that’s problematic for scientists, according to Andria Dawson.

“There are all kinds of uncertainty. And math and stats help us constrain our future predictions and (accommodate) the uncertainty.”

Celebrated medical ethicist Dr. Kerry Bowman says, as a result, “N equals one is not a good research platform at all. Meaning a subject of one is really something you want to avoid. You want a large data set.”

Why?

Award-winning student scientist Isabella O’Brien explains.

“Limiting what you examine? That’ll change the outcome.”

And when that happens? Dr. Victoria Lukasik says accusations of bias start flying.

“There’s this kind of fear based on how scientists are trained that you don’t want to be a person that’s seen as biased.”

For all of these reasons – to remove uncertainty from an uncertain natural world and to maximize statistical accuracy while avoiding the perception of bias – Victoria tells us scientists have been trained to “think of terms of groups, not in terms of individuals. Don’t personalize subjects. Don’t anthropomorphize animals.”

Dr. Kerry Bowman agrees, telling us that individual animal welfare just doesn’t matter to good scientific process: “In science, probably a little less so.”

But that, says Dr. Victoria Lukasik, is a problem.

Why? Because if scientists ignore different methods of inquiry in the pursuit of impartiality and certainty, society might not uncover the best answer to the problems we face.

“New research, new findings – finding out that, oh, actually it’s not what we thought it was – that’s how science evolves, and that’s how knowledge evolves.”

In other words, by trying to avoid bias, Victoria argues that the scientific process might unintentionally force scientists to operate with blinders, ironically leading to biased outcomes.

“Science would benefit from us being less afraid about talking about biases and more willing to examine what ours are. And be transparent about that.”

Scientist Laura Kennedy thinks that’s important. After all, she says, “we base our management principles off the best available science, but there’s a lot of discussion about what that is.”

And helping lead that discussion is biologist and University of Calgary professor, Dr. Shelley Alexander.

“[Science] conservation tends to focus on populations and making sure we maintain populations. Historically we’ve said it’s okay if certain individuals suffer for the benefit of the whole population.”

Shelley agrees that population-level management matters but says that’s not all that should matter.

“It is important that we reach these population goals, but it’s also important that an individual animal is treated with respect and compassion and [that we] reduce any suffering for the greater cause. Both are important.”

It’s a model of scientific inquiry known as compassionate conservation.

“It’s doing science in a way, whether it’s through your education or through your research, [that applies] principles of compassion and welfare to the animals that you’re studying.”

Is there support for this approach? Shelley says yes.

“There is a growing groundswell of scientists who do wildlife research now, who are starting to think in this different framework.”

Critics maintain that by adding emotion to the equation, compassionate conservation runs the risk of creating flawed results. It’s why scientist Laura Kennedy believes it’s a choice between two imperfect models.

“It’s fraught with uncertainty. So, is a better model one that incorporates more of those variables (the value of individual animals to an ecosystem) but has more uncertainty, or one that incorporates fewer variables but maybe doesn’t cover sort of the larger scope of an ecosystem?”

Good question. And whether compassionate conservation is the right next evolution of the scientific process or not, ethicist Kerry Bowman says we should at least do a better job of bringing ethics into the equation.

“The conversation of how much individuals can influence the way the world is, I think is very, very important. And I don’t think it’s anti-science. But I think that’s why the ethics has to be woven in with the scientific inquiry.”

Why?

“Often in the 21st century, you’re looking at very complex situations. So, it’s not this is completely right and this is completely wrong, but in this difficult situation we find ourselves in, what is the best choice? And what would make it the best choice?”

But just because Kerry believes we need to weigh ethics in all decisions – and thinks we should consider the role of individuals in supporting populations – at the end of the day, that doesn’t mean the answer – the best decision – is different from the ones we’re already making.

“Because the concept of an individual being or life, from a scientific point of view, may not always be the highest agenda.”

As an example? How about killing wolves to save the caribou?

As you likely know, caribou are in a spot of bother – with many factors having led to their decline.

It’s unclear when – or even if – we’ll act to save caribou habitat, let alone tackle other major issues speeding up threats to caribou, like invasive species and a changing climate. But there is one immediate threat we can tackle, says biologist Dr. Victoria Lukasik: Predation.

“You can explain it in a way that will sound pretty justified to maybe most people. And the caribou thing is a really challenging situation because, yeah, you can say they should have protected that habitat 60 years ago, but they didn’t.”

As we’ve developed caribou habitat – building roads to access resources and then using them for recreational purposes – we’ve made it easier for predators like wolves to prey on caribou.

The solution? Kill the wolves.

As Victoria explains, it’s the perfect example of science prioritizing populations over the rights of individual animals.

“Justification for the cull is usually that wolves are really resilient; they bounce back. We’re not worried about losing wolves, and you know, fair enough. That’s true from a population dynamic standpoint. And the caribou are really hooped.”

Though it might be an understandable decision, biologist Dr. Shelley Alexander still believes it’s the wrong one.

“The model of killing like this requires you to put aside that these animals have any kind of experience [in life].”

Does it matter? Shelley says to consider the world’s favourite pet – an animal that is the wolf’s closest relative, sharing 98% of the same DNA.

“Even just basically looking at our family pet, we understand that they grieve. Anecdotal cases describe how an animal responds to the loss of its owner or the loss of another family member. And we know that they have strong social bonds. But for some reason, while these things all mimic the human case, we’ve just sort of ignored those and pushed them aside.”

And that, says Shelley, is problematic.

“When animals are living under constant stress, what is that doing to those animals, and how are they going to change their predation rates?”

But what about the caribou? Don’t we have an ethical imperative to act to save them, even if it means killing wolves?

Shelley says, “research that is currently coming out indicates there’s some improvement of the situation. But there are also several research programs that have shown that killing carnivores isn’t going to bring these populations back.”

Stephanie Leonard with the Indigenous-led, Alberta-based Caribou Patrol agrees that predator control isn’t a permanent solution to save the caribou.

“It’s a Band-Aid effect. It’s not solving the problem. It’s a temporary Band-Aid.”

And to that, biologist Dr. Victoria Lukasik asks: “How is it fair to kill hundreds of these animals to try to protect these other animals when it’s not even working?”

In other words, why bother killing wolves if we’re not willing to do what it will actually take to save caribou: Protect the habitat across their vast ranges?

It’s a fair question, but then Victoria adds this bit of insight: “Some people think the wolf cull is working just because they think the caribou would’ve been wiped out.”

Wiped out means zero chance of saving caribou in the Rocky Mountains. But today, according to Caribou Patrol’s Stephanie Leonard, we still have a chance to save a critical member of this ecosystem.

“Yes, predator control is the big reason why some of our herds are stable right now.”

Stephanie believes it’s not predator control that’s the problem – it’s the type of predator control we’re using.

“The poisonings? They don’t work. They kill so much more than the wolves. They poison that landscape. They poison the ecosystem.”

But if we developed more ethical methods of killing? Stephanie says there is a place for a wolf cull.

“Predation control isn’t necessarily a bad thing.”

Emerging biologist Story Warren believes the answer to this dilemma comes down to how we determine if a species is thriving.

“I don’t think that wolves are in danger of going extinct again unless we started a large-scale poison campaign like we did in the 20th century. I think wolves will persist through this heavy hunting, and so that’s thinking on a species [population] level.”

Story adds, “if you’re thinking on an individual level – valuing each animal individually or each pack or family individually – that might be a different answer.”

In other words, Story says, “if your definition of thrive is that the species is present, that’s one thing. If your definition of thrive is that they have intact family groups, that’s a different answer.”

For the head of the Canadian Federation of Outfitters Associations, Dominic Dugré, the answer is clear, and he believes we shouldn’t mess with a good thing: hunting predators has long elevated prey numbers – and that’s what the caribou need today.

“The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation is arguably the most successful initiative that anyone has taken to protect, recover and grow healthy wildlife populations.”

But biologist Dr. Shelley Alexander counters that while some prey populations have benefited from predator control programs, many predators are in peril, suffering population loss, range loss or both. And to sustain predators, according to Shelley, one individual can make all the difference.

“Which individual is it? One individual, from a population standpoint, may be extremely important – whether it’s a genetic reservoir or whether it’s a memory reservoir. [As an example] you’ve got an alpha wolf who keeps the knowledge about where resources are. Maybe that individual might be more important in terms of overall survival [of the population].”

Shelley continues, “in Banff, early on when I was doing research on wolves there, the highway was twined, and they put in wildlife under/overpasses. The pack of wolves would move back and forth using that underpass. When they lost the alpha, the pack ceased to cross that highway.”

It’s a story that’s not unique to wolves.

Sarah Ramirez is a raptor biologist in the United States who has worked extensively on population-level recovery efforts. And she tells us we can’t overlook individuals when caring for populations – a lesson Sarah learned firsthand through an encounter with one remarkable eagle.

“We have this beautiful, big female bald eagle that for 29, 30 years had bred and had put out two to three chicks every single year.”

“We have this beautiful, big female bald eagle that for 29, 30 years had bred and had put out two to three chicks every single year.”

This particular eagle was the third oldest in US history – without her, Sarah believes, the recovery of the bald eagle might not have been as successful.

“Her genetic influence on bald eagle recovery is astounding. That one individual? She had a huge hand in bringing back that population.”

It’s why Sarah believes this question – the debate over whether we should focus on population welfare or individual welfare – isn’t an either/or question.

“Combining both [population-level science and science that accounts for the value of individual animals] is the only way to tackle the biodiversity crisis. I think we need multidisciplinary reactions to these things. We need to look at all the different points of view to be able to save these populations and bring them back.”

But Sarah adds: “If we care about one individual, we care about them all.”

Ken Wu is the founder of the Endangered Ecosystem Alliance, and he has a different perspective.

Ken believes that to advance systems change, we need to forget individuals and populations and focus on ecosystems.

“If we’re going to win the biodiversity battle to try to conserve as much as possible, it’s too slow and inefficient of an approach, given politics as well, to go species-by-species.”

But to save whole ecosystems – and the species that are found within them – he believes we need to be pragmatic.

“I can see a whole lot of guys out there who are hunters who have a real conservation ethic.”

Biologist Neil Fletcher with the pro-hunting BC Wildlife Federation agrees.

“We don’t have time to argue. We really don’t.”

But the head of Humane Canada, Barbara Cartwright, thinks we need to make the time. She tells us we can balance individual animal rights with urgent biodiversity goals.

“That’s the funny thing: We can always do it. It’s just whether we choose to or not. It’s whether our own ideologies get in the way of actually changing the way we behave.”

After all, Barbara says, “we don’t want to cut off innovative ideas [like compassionate conservation] that will help us grow forward. And the species that we’re trying to protect or that we’re trying to study – whether it’s from the smallest field mouse all the way up to our largest whales or our elephants – we need to look at how to not harm the individual when finding the answers.”

Regardless of who you side with, what matters is having the conversation, argues ethicist Kerry Bowman.

“One of the reactions that we see very often in the scientific world is, so what? None of this matters. Well, it does matter. All life matters. All life is interconnected. We wouldn’t be here if biodiversity and the web of life didn’t exist. This is what has supported us from an evolutionary point of view. This is why we evolved and exist because of that web. And we need to respect that.”

But to do that? To find the right balance between populations and individuals, differing ethics and differing science, people and nature? It won’t be easy. Yet it’s imperative that we try.

“I’d say good for you for exploring this question because it’s not a question that has a simple answer.”

- Stephen Herrero | Bear Biologist

Referenced Resources

* Quotes have been edited for brevity and clarity.