We Don’t Know What We Don’t Know

Chapter Three

“When I’m writing poetry, it’s all about the sound of the language, what you can convey.”

Angela Waldie is a poet – and an educator. She’s also a strong advocate for nature.

“(When I was young) I spent a lot of time in the natural world, and spent a lot of time reading. Reading expanded my world in a huge way, for someone growing up in a small town.”

“(When I was young) I spent a lot of time in the natural world, and spent a lot of time reading. Reading expanded my world in a huge way, for someone growing up in a small town.”

What Angela discovered through books, and in her backyard, was a love of language and a thirst for understanding the endless connectivity of nature. But she also discovered a gap between her two loves.

“The challenge with scientific research is getting it out to the public. Like, how do we make it interesting? How do we craft it into something that people really want to learn about and hear about? A good story, a well written article, and sometimes a poem can be a way of actually getting that story out.”

Angela realized she could combine what she loved and what she was good at to help fulfill a need missing in our society.

“Literature can bring the natural world to life by just listening to the stories that people tell and weaving them into a narrative that combines with the sciences and with that personal experience as well.”

And Angela’s succeeded in doing just that – through published writing, as well as through her role as a university professor. However, success wasn’t possible on her own – wasn’t possible with the skills she brought to the table.

“It’s one thing to talk about how writers portray the extinction of species, or natural places and landscapes. But there’s always been kind of that place that I feel my expertise isn’t answering all of the questions that students have, or (that I’m) not able to engage on the level I could.”

“It’s one thing to talk about how writers portray the extinction of species, or natural places and landscapes. But there’s always been kind of that place that I feel my expertise isn’t answering all of the questions that students have, or (that I’m) not able to engage on the level I could.”

Enter Andria Dawson.

“Science is really about the systematic study of the natural world. And we’re always asking questions like, ‘How are these two things different? Are they different? Are they the same? How are they different? Does X cause Y?’ And the way we address those questions is using mathematics and statistics.”

Andria is good at math and she too is passionate about our relationship with – our impact on – nature.

“As I become more of a math ecologist, learning about ecology, I really start to understand that everything is connected.”

However, Andria isn’t a storyteller and, as she explains, that’s where science struggles: Communication.

“Science doesn’t tell you what to actually do with the science. It can tell you what the evidence suggests and we can write down equations that describe relationships between things. But it doesn’t tell you how to feel about what we learn or what to do with that information.”

Enter Angela Waldie.

“When I met Andria, it was kind of the perfect pairing of being able to bring together the literature and the science and the math together.”

It’s a unique partnership. Both Angela and Andria do what they love and are playing to their strengths. And by working together, they’re also complementing their skills and finding creative ways to help each other reach new heights – in work and for nature.

It’s a unique partnership. Both Angela and Andria do what they love and are playing to their strengths. And by working together, they’re also complementing their skills and finding creative ways to help each other reach new heights – in work and for nature.

“People are very resistant to having to think – to think hard – about these different kinds of problems. And, so, by trying to bring different disciplines together – the science and the literature describing the science, whether it’s through fiction or through media – I think it tells people how those two disciplines are different, but also how they are the same. It does push them to think.”

And we all need to be pushed to think harder about the issues we face and the decisions we must make – in our lives and in our world.

As an example? What should we do when we discover orphaned or injured wildlife?

“I’ve got three bear cubs that just came to us. The mother was shot. The cubs were still in the den. The conservation officer got them out of the den, called us, we picked them up. They’re here with us now. We’re offering a chance for orphaned wildlife to grow up and mature and be returned back into the wild population. We’re offering an opportunity to minimize our footsteps when we inadvertently hurt an animal.”

Meet Angelika Langen, co-founder of the Northern Lights Wildlife Shelter and star of the TV show Wild Bear Rescue. By combining her love for animals and her skills as a scientist, Angelika is a trailblazer, having worked to find ways to rehabilitate and re-release injured and orphaned bears into the wild.

Meet Angelika Langen, co-founder of the Northern Lights Wildlife Shelter and star of the TV show Wild Bear Rescue. By combining her love for animals and her skills as a scientist, Angelika is a trailblazer, having worked to find ways to rehabilitate and re-release injured and orphaned bears into the wild.

“We have rehabbed – us here at Northern Lights – almost 500 bears now, including 27 grizzly bears and none of the bears that we have radio collared have not made it to hibernation.”

That’s a lot of bears returned to populations that, in some cases, are struggling. And according to Angelika, when it comes to sustaining species – protecting biodiversity – we don’t ask big enough questions: Like can saving one individual help an entire species?

“We do recognize that an individual has a right to live. I think that’s fundamental to the whole idea that we’re not just looking at the big picture, but we’re realizing that the big picture is built one step at a time.”

Angelika continues, “When you’re building a house, you’re not putting one block down and you have a house. You take stones and you put them together, and that makes a house. Wildlife is the same thing. Every animal has a place in this world, every animal has a role to play. By taking these animals out, you’re making holes in the whole picture, and that’s going to have an effect on the rest.”

In other words, we usually investigate top-down threats to wildlife populations, but Angelika says that’s partially because we limit the scope of our questions. If we ask how wildlife rehabilitation might help create a bottom-up approach to conservation, Angelika believes we might find new ways to help biodiversity.

Right, ethicist Dr. Kerry Bowman?

“I’m very conflicted on this.”

Wait, what?!

“By having animal rehabilitation – wild animal rehabilitation – you’re giving a clear message to a lot of people, including younger people, that these lives matter. But having said that, what concerns me is there has been so little research into animal rehab.”

Kerry is a medical ethicist and specializes in helping policy makers globally ask the better questions when they struggle with the unknown.

“We have to ask as many questions as we can. Good ethics is based on good science.”

But Angelika Langen says wildlife rehabilitation is based on good science.

“John Beecham has published a number of papers and has taken together the results from lots of different areas that proves that bear rehab works. The animals survive. They do well out there; they do not become problem bears. I keep on challenging (critics) to bring me these scientific papers that show that it doesn’t work.”

Dr. Kerry Bowman’s response?

“I would question that.”

Angelika says that skepticism only exists because critics don’t just look at her scientific track record, but also look at the science of rehab operations that don’t hold themselves to the appropriate standards. That, Angelika argues, isn’t an issue of scientific validity; it’s an issue of too little government regulation.

“If the standards would be adopted (by government) and if they are applied, then this would be no problem. The problem is that there’s people out there that are doing bear rehab and they’re not following the standards. They’re putting out animals that are becoming problem animals and that then gives ammunition to those people who say that rehab doesn’t work. So, the key is that we’re developing these standards, adopting these standards on a wide scope and saying, ‘Okay, we can do this, if we have this’.”

“If the standards would be adopted (by government) and if they are applied, then this would be no problem. The problem is that there’s people out there that are doing bear rehab and they’re not following the standards. They’re putting out animals that are becoming problem animals and that then gives ammunition to those people who say that rehab doesn’t work. So, the key is that we’re developing these standards, adopting these standards on a wide scope and saying, ‘Okay, we can do this, if we have this’.”

Critics have argued that by adopting standards, it endorses using precious resources to help individual animals when we lack the money to save entire populations. But Angelika, again, doesn’t believe it’s an either/or scenario. She believes we need multiple approaches to protecting biodiversity since our current strategies aren’t working particularly well.

Plus, Angelika adds, rehab clinics like Northern Lights “are footing the bill for all of this. The problem is the government doesn’t see it as a priority. When I go in and talk to them, I keep on hearing that this is not a priority. So, the only way (creating standards and normalizing wildlife rehab) will become a priority is if the public makes it a priority.”

But for that to happen, we need to know more, according to Dr. Kerry Bowman.

“We do not understand what we don’t understand.”

It’s why we need to use own unique perspectives and our own journeys to ask the better questions, helping us understand if this is the better way forward.

“When we started, we kept saying, ‘We can (rehab orphaned and injured) grizzly bears, too’. We were told, ‘No you can’t’. But we just kept coming. We said, ‘Then give us the guidelines, say what we need to prove’. And then we did a pilot project; we answered those questions.”

And grizzly rehab is now legal in BC, even though other jurisdictions in Canada haven’t changed the laws. The long journey of gaining approval in her home province would have turned many people off, but Angelika has a different take.

And grizzly rehab is now legal in BC, even though other jurisdictions in Canada haven’t changed the laws. The long journey of gaining approval in her home province would have turned many people off, but Angelika has a different take.

“It’s on us. We wanted the change, so we brought the funding in, we brought the man power in, we tried to prove that this works. And it’s up to us to make the public, or the high school student, say, ‘This is worth the cost, I want to get involved because I believe in what they’re saying’.”

And whether you agree with Angelika or not, the more important point? When it comes to complex debates, a hunting advocate tells us:

“Ask questions. Why? Where? And I think you’ll be further ahead than just making these snap, rash decisions and judgements.”

Anthony is an influencer on X, known as the Thankful Outdoorsman. He believes that too many people can’t be bothered to understand what they don’t know they don’t know – or even what they know they don’t know.

“In today’s society, with instant gratification, instant news, instant information, people are very quick to jump to conclusions.”

That’s true of wildlife rehabilitation and hunting and, well, just about everything. As an example?

“Well, first of all, a lot of people don’t know where their meat comes from. And I know from posting things on X during in hunting season, I have been attacked for hunting. (You can’t believe) the amount of people that actually say, ‘Why don’t you go to the store and get your meat, as opposed to killing an animal?’ And that shows you there’s a disconnect right there.”

“Well, first of all, a lot of people don’t know where their meat comes from. And I know from posting things on X during in hunting season, I have been attacked for hunting. (You can’t believe) the amount of people that actually say, ‘Why don’t you go to the store and get your meat, as opposed to killing an animal?’ And that shows you there’s a disconnect right there.”

Donna Kennedy-Glans is a former Alberta cabinet minister and she agrees with Anthony.

Whether the issue is animal rights, hunting rights or “the proverbial ‘environment and the economy are two sides of the same coin’: When I hear that, because I’ve heard it a million times, my reaction is, ‘Okay, what side’s he on?’ Because (these issues have) become the polarity.”

And that’s a problem, Donna explains.

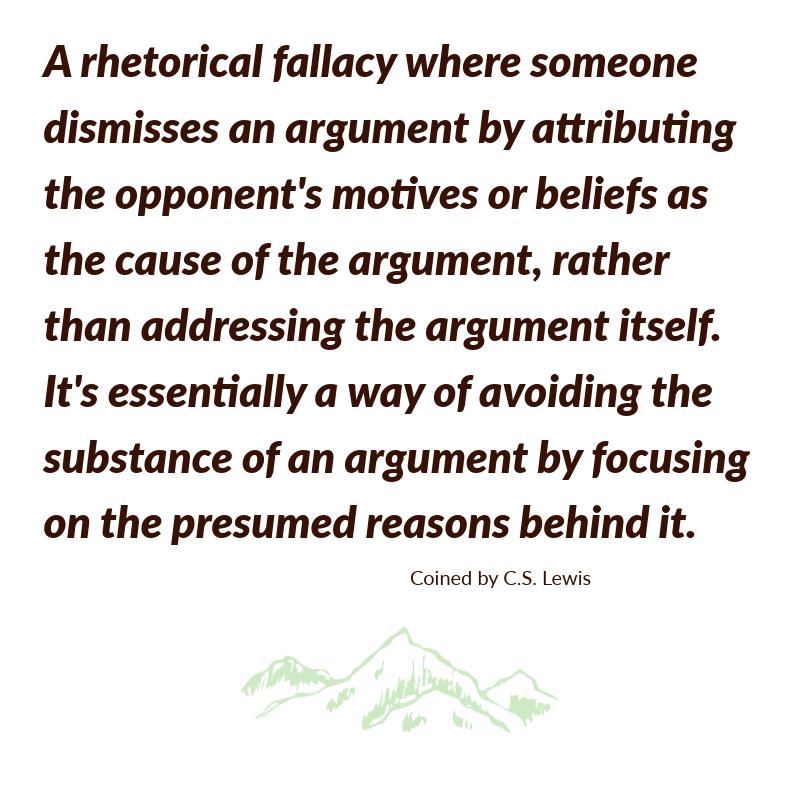

“It’s easy to say, ‘Well, their motive is they want money. Or they want power. Or they want influence. Or they want the world to look like the way they want it to look like’. And we stop thinking about what they are saying. C.S. Lewis called it ‘bulverism’. The idea that you should always look at the facts and ask: ‘What are they saying?’ And you also need to ask: ‘Why and what is the motivation?’”

“It’s easy to say, ‘Well, their motive is they want money. Or they want power. Or they want influence. Or they want the world to look like the way they want it to look like’. And we stop thinking about what they are saying. C.S. Lewis called it ‘bulverism’. The idea that you should always look at the facts and ask: ‘What are they saying?’ And you also need to ask: ‘Why and what is the motivation?’”

If we stopped to ask Anthony the Thankful Outdoorsman his motivation?

“If you’re not eating what you’re killing – if you go right to the fundamentals – you’re taking a life for nothing. These animals are fighting for their lives and they have it hard out there, through the conditions and the predators. You don’t just walk out into the bush and shoot something for the heck of it.”

And if we’re surprised that a major pro-hunting X celebrity has a nuanced view of hunting issues, it’s because we made a faulty assumption. It’s something so many of us do when we face gaps in our knowledge.

“If you hear somebody say they’re a hunter, don’t think trophy hunting. Don’t make the judgement. Ask questions. Have an open mind. Ask, ‘Why do you do it? How do you do it? Do you think it’s unethical to do this? Do you think it’s easier to buy meat in the store? Do you think that it’s unethical to raise cattle?’ Ask questions. Be open minded. I think if people are, then people will learn.”

Anthony wants people from all sides of the hunting debate to be more open-minded and debate hard questions, like the consequences of predator management.

“If you cull bears, if you cull coyotes – I think it can be done responsibly – but who is going to manage that? And in the past, the government hasn’t been very good at that. People, once they get it into their minds that predators are bad, it’s just open season. And we just can’t have that either because it is balance. If the (prey) animals decline, the predators decline. The (prey) animals come back, the predators come back. It’s a balance that’s been going on for thousands of years, and we’ve never had the cull in the past. A long time ago, our ancestors didn’t have to deal with this. There was trapping; there was a balance. And I think balance is the key.”

“If you cull bears, if you cull coyotes – I think it can be done responsibly – but who is going to manage that? And in the past, the government hasn’t been very good at that. People, once they get it into their minds that predators are bad, it’s just open season. And we just can’t have that either because it is balance. If the (prey) animals decline, the predators decline. The (prey) animals come back, the predators come back. It’s a balance that’s been going on for thousands of years, and we’ve never had the cull in the past. A long time ago, our ancestors didn’t have to deal with this. There was trapping; there was a balance. And I think balance is the key.”

But balance is hard to find, Anthony says, when we don’t try to learn what we don’t know.

“If people are one-sided and very blinded, they shut down and it’s my way, or no way. And that’s a problem.

That is a problem.

After all, the issues at the intersection of people and nature are often stuck because too many are convinced our choices are either/or questions. But, of course, life just isn’t black and white.