Here’s How

Chapter Five

Look, our system isn’t perfect, but it is ours and, though we’d sometimes prefer it not to be true, it is a reflection of us.

Can our visual stories get things wrong? Can our storytelling and sharing platforms fail? Of course. Because we can be wrong; we can fail.

Can the system be broken or slow? Absolutely. We’re broken and slow at times.

But our world? Our nation? Our system? It’s not static. It can be pushed and prodded and tweaked and improved. We can use art and storytelling within our democracy as tools to better our world.

And whether you believe our system will save us from our ills – or is what ills us – it’s our democracy that provides us with the space to use art and story to have this debate and decide on a direction that the majority of our peers can live with.

“You look around the world at what’s going on and you do sense that there is a fragility to our democracy. It is something that needs to be protected, needs to be nurtured.”

Mike Farnworth isn’t just a senior cabinet minister in the BC government, he’s also a passionate advocate for democracy. When Mike isn’t working here, he’s working here and here and here – in places that have been fighting to implement an imperfect process just like ours.

“We come in with our experience under a long history of democracy in this country, and a way of doing things. And you meet people for the first time and you work with them, and you say you can do this this this and this. And then you suddenly realize, ‘hey, wait a sec. That approach may not work here for a variety of reasons’. What’s important is the principles. So it’s transparency or consultation. Well what does that look like? It can vary from place to place, it can vary in different cultures and different ways of doing things. But what’s important is not how it’s done, but that it is done.”

But Mike argues that for those democratic principals to be upheld, they need to be understood and respected.

“There needs to be a greater awareness and understanding of exactly what it means. The rules that we have in our chamber are the rules that we have in terms of the House of Commons in Ottawa. The fundamental basis upon which our institutions rest.”

Sam Sullivan is Mike Farnworth’s political opposite and his sometimes foe, but he agrees we need a better respect for our democratic system.

“Thousands and thousands of years of evolution and most of the time these decisions in human history are made by blood and thuggery. That is the human reality of our government over time. It’s only in the past few hundred years that we got to a place where the government can change and no one dies. So this is a huge achievement, especially for a guy like me who doesn’t want to die. We love this idea that we have a civilized – maybe not very pretty – but a system where we talk things through and we have rules that we all agree are the rules, and that results in government. And that results in decisions. A small group of people is able and is credible and legitimate to make those decisions for everybody.”

That’s why Mike tells us; ““Of all the systems out there, this is still the best system we have and you can make a difference. There are many examples around the world of young people who make a difference.”

In other words, if you reject a politician or a party or how elements of our system works: Fine. Get involved and work to change it. Just don’t throw out the baby with the bath water. We’re lucky to have what we have and we mustn’t take it for granted. That’s why Mike wants to remind us “It’s extremely important, when you turn 18, to vote. At the same time, if there’s something you’re interested in, get involved with a group that’s involved in that. Be an advocate, go talk to your friends, talk to you parents, talk to your local elected officials, talk to your city councillors. Those are all ways in which they understand that, ‘you know what? People care about this’ and if there’s something you passionately believe in, get involved with it and stick with it. You’re the future and you cannot go wrong by being involved in something you believe in.”

Just know we can’t expect our ideas alone to win the day; we must remember that we’re part of a system and every idea must connect with, work with or even overcome the ideas put forward by our peers from across our country. It’s why we can’t skip past the process – even when others think we can or should.

“I had a press conference, and after you survey the document and you talk about it, one of the journalists say, ‘yah, but what do you really stand for?’, and I thought, you actually just heard a pretty dramatic statement of what I really stand for, but you just don’t get it. And I think process is something that’s very hard to get people excited about. And particularly media, they don’t see that the substance, the outcome, is very much a reflection of the process.”

Our former prime minister is right: If you haven’t already realized it by now, process matters. But don’t just take Kim Campbell’s word for it. The late Ian Waddell recalls a time when he was a government minister and elected to overlook the process.

“I put a freeze on grizzly bear hunting and I didn’t win the battle. I got defeated. And I should have won it, but I didn’t do my preparatory work in government to get people on my side, to get support.”

Art-meets-design innovator Jerry McGrath believes that’s why we need to better appreciate the importance of process not just here, but in our own lives as well.

“Process matters because it creates a space for other smart people to contribute.”

Jerry tells us how we design our ideas – how we advocate for our ideas – often matters as much as our ideas.

“When we assume we know what the right path is and we design for that, we’re not opening ourselves up to being wrong. When we create a process that allows from contributions from different people, then we’re actually open to the fact that our knowledge is incomplete. Having the economist, the artist and the scientist in the room, well when you have all those people in the room and you’re open to their contributions, you get a much richer picture of what’s possible. So for me, process matters because anyone who thinks they know the path from A to B is probably going to have a mediocre outcome. Anyone who believes that B matters, and any way of getting there is important, is probably going to be able to invite more people to participate and get a better outcome in the end.”

Which makes sense. The problem is, Jerry adds, we usually limit our processes; we limit the voices we engage.

“What everyone needs to understand in their work is that how other people feel in a particular situation that you create matters a lot more than what you’re trying to do. When we all share a particular feeling, a passion, a curiosity, a sense of awe, a sense of wonder, then that’s a shared moment that allows each of us, regardless of where we’re coming from to participate positively to the final outcome.”

For that reason, multi-platform artist-storyteller Maggie MacDonald tells us we should live by these words:

“Nothing for us without us. So not just creating a program that’s, say, ‘oh, here’s a program that I, from a settler community made for indigenous communities’. Nothing for us, without us. Definitely include people when you’re creating a program, or creating a project – include the people you want to talk to in it from day one, so you’re not just putting your own perspective on something.”

The long-time head of the Canadian Parks Council, Dawn Carr, agrees.

“Process is often – as challenging as this could be – process is often more important than the product, or the outcome because the process determines what the final outcome and decision will be.”

Dawn adds “embrace the tension, embrace the ambiguity, and really start to experience and get experience in what collaboration looks like. It’s hard, hard work and it can take a long time. But that hard work of having conversations and truly understanding what collaboration looks like is critically if we’re actually going to be successful in achieving these long term outcomes of maintaining and sustaining some of these special places.”

She’s not wrong. But let me play Devil’s Advocate for one moment. For a long time in our society, we valued outcomes over process and that, in many ways, led to some of the problems we face today. To compensate, we’re now valuing process over outcome – almost at the expense of outcomes, as biodiversity guru Harvey Locke argues.

“This idea that we’ll continue to turn little dials, fine tune the radio because there’s a little bit of fuzz, ‘well if we just get it right, it will be just fine’. Everybody knows that’s nonsense.”

He too is not wrong. The erosion of our democracy – the increasing challenges facing people and nature – is partially born out of frustration that our processes aren’t delivering outcomes fast enough. In other words, we might be swinging too far the other way; forgetting that outcomes do still matter in our world, especially when we can’t all agree the right process, as former mayor of Vancouver Sam Sullivan argues.

“You may have this very pristine view of how the world should work, but it’s not going to work. It’s not going to get you anywhere. You need to get things done.”

As we see almost everywhere in society, those who advocate for process – for taking more time to perfect the outcome by including more voices in decision-making – don’t always include dissenting voices from different parts of the political spectrum or even those who believe outcomes still matter. That creates a silo-ing effect and, ironically, so-called good processes don’t always yield good outcomes either.

Here’s what I’m trying to say: process matters. A good process will yield better results. But with urgent issues in a divided world, realism is also important. Outcomes count. It’s why this advice from Maggie MacDonald might be the most important of all.

“Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. So that’s the idea that if you spend all of your time trying to do something totally perfectly, so you’re in your process and you’re honing the process…and you’re trying to make it absolutely perfect, then you might not ever…finish the product and get something out there that’s pretty good. Put in the effort, but don’t wait for it to be absolutely perfect before you go ahead.”

That’s a critical point and so too is this insight from former Alberta cabinet minister and author of Teaching the Dinosaur to Dance, Donna Kennedy-Glans.

“I just do. I think you learn so much in doing. And then if it’s not right, you don’t do it anymore.”

Donna adds “you can talk about it a lot, but I think we’ve got to do.”

Creator and life coach Shawn MacDonell agrees, telling us that good process isn’t always about perfect planning, but can simply be wild experimentation.

“You don’t even have to tell the story sometimes, sometimes you just live the story. You’re like, ‘how do I do that?’,…well, just get away from your desk. Think outside the box…kill the box, forget there was a box.”

What does that mean exactly? Well, for scientist Sandra Nelson, she says it means “listen to my gut instinct, but not rely on it and question it all the time.”

And for Dr. Aleem Bharwani of the Cumming School of Medicine, it also means within a process of experimentation, not forgetting that “in citizen led diplomacy come two principles of being an honest broker and the goal should be to facilitate honest, respectful dialogue.”

In other words, as Global National anchor tells us, just strive to be a good human.

“Being kind and thoughtful and open to new ideas.”

And don’t forget, we’re our best selves when we’re happy, adds Shawn MacDonell. It’s why he believes the best ideas – the best processes – start with this simple concept: “whatever makes you happy, do that. Because if you do that, and then the other person does that, and the other person does that, then were all…happy. It’s not a secret. It’s not a mystery. It’s not rocket science here. It’s just – don’t be sad. Try really hard to not be sad and encourage other people to also not be sad and we will be in a much better place. Nature [or] whatever way you want to look at it. If you’re happy, the world’s going to be a better place, for sure.”

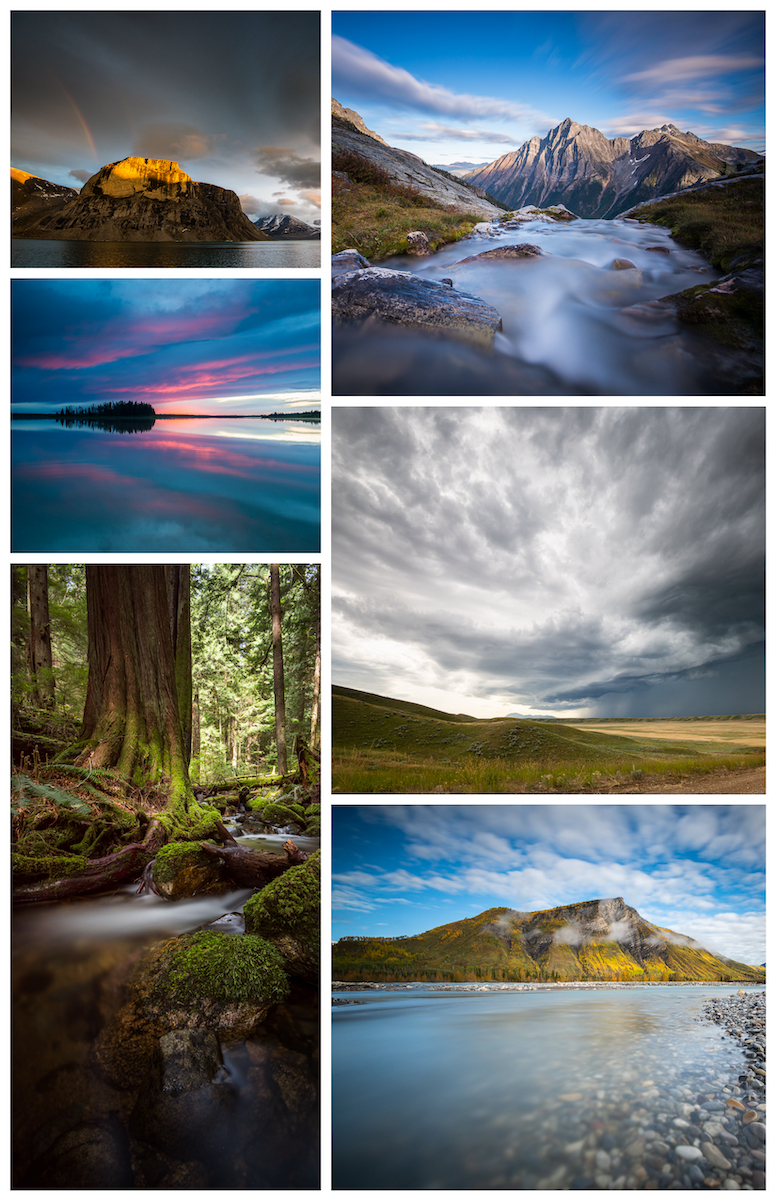

Don’t believe him? Look to nature, Shawn argues.

“One of the ways that nature teaches us to be more real, how to do what you love, is you just have to sit and look at animals. I mean – they’re doing what they love. They’re not doing anything else, nobody else is making them do things, no one’s taught them to do a different thing. They need to eat a salmon out of the river? They’re going to get a salmon out of the river. They’re just doing it. They’re not building a cabin, and then, ‘oh the cabins not insulated enough, we have to built a better cabin, so we need a better cabin’. They’re not thinking of all these ways to screw up this land. We’re the only ones that are doing that. Nature is doing what it loves every day.”

So heed Shawn’s advice – heed nature’s advice. Be a good human and work to create real relationships with other humans. And with nature.

Listen to what nature has to say and listen to what other humans have to say – but not just to respond. Really listen to hear what needs to be heard. And when we have truly listened, remember that in a real relationship, listening is a two-way street; we need to feel heard, at some point, too.

And when the time is right to make our voice heard? We need to remember to use it to empower all voices and all communities, both inside and outside of our work and our system. Because lecturing helps no one – we don’t need more division; we don’t need more groupthink or more cliques.

But we do need more people to find their voice. After all, when we all learn to use our voices effectively, our ideas improve and grow – and so too does our ability to balance people and nature.

This is how good visual storytelling leads to a more engaged and thoughtful citizenry, a healthier democracy and better ideas for people and nature that endure.

And, sure, sometimes the pace of change is slow. That can be frustrating, even for a cabinet minister like Mike Farnworth.

“Even on the inside, but what’s important is you know that it’s happening and what you want is to be there long enough to see it come to fruition. Democracy works, but it just works slowly. Government works, it can often take time, but it does work.”

Which sometimes we forget, the late Ian Waddell explains.

“You think, ‘well, why was it so long?’. It takes a while to build on an issue. You say, ‘it’s going to take 20 years, or a while to do this’. So what are you going to do?”

Not quit – certainly Ian Waddell never quit on what he cared about. Plus, as Sam Sullivan points out, “it’s a good thing that things aren’t easy. Things shouldn’t be easy because if it’s easy to just throw things through and put things through, some pretty bad things can come through as well. So the system is meant to put a break, deliberate and consider and to really think, ‘is this the right way to go?’ because there’s a lot of great looking ideas that are terrible.”

It’s why, when we get frustrated, we need some perspective – like this from Harvey Locke.

“If it takes me 20 years to do something, that’s ok. As long as it happens. And if I never get any credit for it happening in the 20 years, that’s ok. As long as it happens. Because the idea for me is, I care about the well-being of nature and humanity.”

After all, as journalist and community builder Salimah Ebrahim reminds us, the pace of change doesn’t matter; it’s the bigger arc of history that counts.

“As much as I’m burning with, and a lot of young people are burning with, the desire to see everything change immediately, I think realizing what you can do over a few months, over a few year and over a decade, to move the conversation forward, it’s amazing.”

Salimah adds “all of this is still really, really early on and it’s really, really complicated when you look at the spectre of history, of injustice that has happened. So no one is going to be able to come up with a perfect solution in the beginning, I think what we hope is that you’re going to push things forward a little bit down the road until they become the status quo and we can really make change. And sometimes history looks like that, and all of a sudden there’s a fundamental seed change. We’ve seen this on a range around human rights around the world. There’s a different type of urgency with the environment.”

Which means we need to channel urgent patience; we need to be realistic optimists. To that end, Salimah says “the people that can thing in zigs and zags, who can think horizontally are the ones that are going to be able to use this toolbox of ideas and come up with solutions.”

We all have that ability within us and, as Mount Robson’s Elliott Ingles reminds us, “we’ve kind of got one shot of protecting these places. You know? There’s one planet, we’re all part of it, we’re all together. And I think one person makes a difference.”

In Canada, depending on who you are, your perception of that reality will vary. Your faith in being able to impact our system will differ. And yet for all its successes and failures – its opportunities and its weaknesses – our democracy is just that. It’s ours to destruct and create, to shape and influence.

“Vote. Every single time you have an opportunity to vote for an elected official – get yourself out there and do it. People died for the right to vote.” – Ilona Dougherty

For whether we realize or not – take advantage of it or not – we’re not just the authors of our own story. Through this process and ours, we’re the contributing authors to a much bigger story: the history of our generation.

“Say one of you was an architect in the 1400’s in a European town, and the local decision makers came and asked you to design a new cathedral. You would begin that task knowing you would not live to see it completed. It might be a grandchild of yours or granddaughter of a neighbour that compelted the final renderings for the spire, 4o, 50, 100 years since. There are cathedrals that began in 12oo that got completed in the 1400-1500’s. So generations hence. If someone listening to this was a stone mason in the 1400-1500’s working on that, laying the cornerstone or perhaps the foundation blocks, they would do so knowing that a grandchild of theirs in the same trade 50 years later could be building on top of the work they did. So what they would do is be extra careful – to use good materials and to build solidly. Because long after they passed away, someone that they cared about because of hereditary, would need to rely on a strong foundation as maybe they worked on the third floor, or they worked on the arches or they tried to design new ways to build with stone. Someone who’s 14 or 18 years old thinking about when they’re 55 or 65 – it’s just so far off and it’s hard sometimes to make it matter. But the fact is that each of us has consciously or willing to acknowledge or not building upon and benefitting from things that other people did. So cathedral thinking, when you’re laying that foundation, or you’re doing the initial design and you know that you won’t likely complete it, what you’re doing is keeping the living generation tethered to the future. But you’re also getting involved in unfinished work. I think we should all be involved in unfinished work. Knowing that, at some point, you hand it off.” – Rick Antonson