Estimated Read Time: 42 minutes

Canada at a Crossroads

Okay, so Canada is at a crossroads. On this, we agree. But when you stop and think about it, what else can we agree on? If we’re being honest, the answer is not much.

“We kind of have to ask the question, were we ever united all in this together?” – Shachi Kurl | Pollster

All in this together? Elbows up? Let’s get real. When the puck’s in deep, far too often we stop playing as a team. And while we might appear to be on the same page in the wake of US President Donald Trump’s threats, in reality, unity is only about a centimetre deep.

“I think you’ve hit the nail on the head. It’s not very deep. It’s covering over some long-standing feelings and those long-standing disagreements in Canada.” – Hamish Marshall | Conservative Strategist

And those long-standing disagreements in Canada? Business leader and former leader of the Conservative Party of Canada Erin O’Toole says, “the pandemic exacerbated existing tensions in our country.”

And pollster Shachi Kurl agrees.

“Think the thing that has changed in the last several years, call it polarizing, or call it the surfacing of a lot of discordant views – so a lot of opposing views. Whereas people in the past might not have been as comfortable saying, ‘you know, I don’t really agree’, because we’re Canadian and we like to be nice.”

What happened during the pandemic? Erin O’Toole tells us:

“We saw a lot of breakdown of social cohesion because of the isolation, because of the fear of the pandemic, and some politicians took advantage of that.”

Though we tried being all in it together, we ended up more divided than ever. As scientist Kate Moran argues, some of us vilified the medical profession when they didn’t give us information that aligned with our world view.

“It became even worse during covid and that kind of misinformation has spread.”

And as Erin O’Toole adds, some of us also vilified anti-vaxxers, deepening distrust in science and democratic institutions.

“It just hardened positions, rather than educating and enlightening and listening. I do think we’re going to continue to pay for that decision in the years to come.”

How so?

“That’s what’s caused the polarization both east and west, rural versus urban, the climate apocalypse left and the drill baby drill right, far more than the pandemic and the isolation from that. It was the over reliance on social media and the destructive elements of it.”

“That’s what’s caused the polarization both east and west, rural versus urban, the climate apocalypse left and the drill baby drill right, far more than the pandemic and the isolation from that. It was the over reliance on social media and the destructive elements of it.”

And that, according to Erin, is the bigger issue. The pandemic allowed echo chambers and misinformation to take root on all sides, deepening those existing divisions in our country.

The divides Erin listed are getting worse, not better, in part because each of us increasingly subscribe to our own truth.

Why is this a problem? Lawyer and democracy advocate Peter Biro explains.

“When many people believe, as they do today, that each person is entitled to their own facts and there can’t be any universal commitment to truth and to reality. Where universality, where the very idea of any kind of absolute truth on any important question, is ridiculed is disbelieved, is demeaned.”

East versus west, north versus south, urban versus rural, pro-environment versus pro-economy: when each segment of our population becomes closed off within their own echo chamber, believing only in their own truth? It becomes very hard for a country like Canada to move forward, as Peter argues.

“There can be no shared understanding of facts, of knowledge and of truth, however provisional. There can be no consensus generation, no ability to make decisions together based on a common understanding of the important realities, the relevant realities in the world.”

This is a problem at the best of times and it’s especially a problem when Canada is facing multiple crises.

To get through this hard stretch as a country – to protect our economy and our sovereignty while still finding room to address other critical issues that haven’t just gone away – we must do a better job of understanding why those we disagree with hold a different view than our own.

Where to start?

How about right here.

“We are now kind of at the thorny, crash prone intersection of, ‘well, what are we going to do?’ And that’s causing a lot of people to pull apart. Because even if we lived in a world where there were no actions required at the end of agreeing with something – let’s all agree climate is changing, and that’s bad. What are we going to do about it? That’s where the difficulty comes down.” – Shachi Kurl | Pollster

You see, in many ways, this is the metaphorical, thorny, crash-prone intersection pollster Shachi Kurl is referring to. After all, in Canada, so often what divides us isn’t geography or language, but rather our perception of which road we should take here: the intersection of the environment and the economy.

Why is this at the heart of our national divisions? Well, economics expert Heather Scoffield asks:

“It’s worth thinking in Canada – what do we have that we can show to ourselves and perhaps the rest of the world, if they’re interested, that allows for everybody to be more prosperous and for us to all have at least a bit of extra space in our heads to pay attention to the broader social good.”

The answer is pretty obvious, isn’t it? Canada’s natural advantage, of course, is our natural resources.

“Natural resources are obviously something that Canada’s always, always had a lot of. Do we just continue along the path that we’ve been going through since time immemorial in terms of producing these things? Or do we figure out how to do more of it in an environmentally compatible way and in a way that makes some of that processing of those natural resources based right here in Canada so that we’re a little bit more resilient and a little bit more autonomous in how we develop all those things? I think that’s certainly one area that we have a lot of potential.”

That, of course, is the question and it’s one worth pondering at this intersection, in the heart of your classroom, Mount Robson Provincial Park.

That, of course, is the question and it’s one worth pondering at this intersection, in the heart of your classroom, Mount Robson Provincial Park.

You see, Mount Robson is along highway 16. If it’s not already, it will undoubtedly soon be Canada’s official national energy or major project corridor.

Pipeline? Check. Fibreoptic line? Check. Railway? Check. Highway? Check. And soon we might have a lot bigger and better versions of each through this, the Highway 16 corridor.

You see, the thinking goes like this:

We’re not self-reliant, and that blame goes back generations. For too long, we’ve taken the easy way out because it was, well, easy.

We haven’t created reliable transportation corridors across our country to allow for easier travel. We haven’t built infrastructure to develop and share our resources within our borders. We haven’t created nearly enough capacity to trade with nations beyond America.

Fixing this? Well, it takes time. And money. And for aforementioned reasons, people might not want to invest in Canada. It’s why economist Trevor Tombe opined that Canada should put all our effort into improving our economy. How? By creating a better investment climate, something Tombe and many economists think we can still achieve to some degree of success if we:

- Reform our tax code

- Reduce regulatory red tape and remove internal roadblocks

- Stop political opposition to big projects and build better infrastructure

Why choose this road? Well, as Heather Scoffield explains:

“Certain areas of our economy that are fantastic and that the world wants more of, and that if we focus on a handful of really excellent things as a country and make them shine and make them brilliant, I think that that can go a long way to pulling up the whole country.”

Right. That makes a lot of sense.

But what about the environment? Conservative strategist Hamish Marshall argues:

“If you’re building a pipeline, if it’s designed and engineered properly, has almost no impact to the environment, and could be reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Asia if you’re exporting Canadian natural gas.”

And while Mount Robson Park won’t be developed if we choose this road, many landscapes in this country will be opened for development – and their bounty moved to markets right here, with an expanded Highway 16 infrastructure corridor.

In choosing this road?

“It’s not something that we can have happen quickly, because we’ve taken so long. Even if you made a decision on a pipeline today, it’s not going to get built for years, so we have to make a long term strategic decision to try to diversify who we trade with. The Trump threats and the tariffs that we’ve seen for the last little while force Canada to look at our place in the world, look for other opportunities.” – Hamish Marshall | Conservative Strategist

And what other opportunities might exist at this intersection for Canada? Well, there’s this road, one that takes us to the heart of Mount Robson provincial park.

And this park? It’s more than a famous view of a 3954-metre hunk of rock – the tallest peak in the Canadian Rockies. This park is also home to four eco-regions – including a rainforest – that sustain the ecosystem’s 182 bird species, its 42 mammals, the four resident amphibians and one species of snake.

And this park? It’s more than a famous view of a 3954-metre hunk of rock – the tallest peak in the Canadian Rockies. This park is also home to four eco-regions – including a rainforest – that sustain the ecosystem’s 182 bird species, its 42 mammals, the four resident amphibians and one species of snake.

Mount Robson is but one of hundreds of similar parks across Canada that act as reservoirs of biodiversity. And it could be one of thousands if we choose this road.

You see, because of our small population and large geographic size, we’re one of a handful of nations globally – along with places like Russia and Brazil (neither of whom are exactly world leaders in advancing global good at the moment) – that can actually save biodiversity.

As the United Nations’ David Cooper tells us:

“Look at Canada. We have this vast boreal forest. We need actually to maintain practically all of that boreal forest and maintain it as boreal forest – whether or not it’s a formal protected area – if we’re going to maintain the life support systems of the planet.”

And political scientist turned Liberal MP Dr. Will Greaves adds,

“We need to really recognize the extent to which Canada and Canadians have an obligation to safeguard in a much more diligent way, the biodiversity and natural heritage that we have in this country. Not just for ourselves, although definitely that as well, but in fact, because it plays a vital role in global stewardship that Canada has such a vital wealth of natural ecology, and in particular the role of the boreal forest that are of global significance. We really have an obligation to safeguard that on behalf of people all over the world. This is a global responsibility that is borne by Canada.”

That’s the environmental case, but what about the economic case? Angel investor Randall Howard asks:

“What kind of investments do we need to make in our economy, recognizing that pipelines for oil and gas are for fossil fuels which are fueling the climate crisis and obviously on their way out. So there’s a timeframe for that that we need to remember. Given that’s the case, Canada has very important country wide choice to make. And that is: how long do we have to decarbonize our economy, to wean ourselves from oil and gas? Is it five years? Is it 10 years? It’s probably more in that range. So that’s a lot of jobs to move in that time. Canada has had a choice – we can change that job makeup around our fossil fuel jobs, create new companies that are going to dominate the world, and we can be healthy, and we can be wealthy and economically vibrant and maintain a good quality of life. And there’s the alternative. So I think that we are standing at a crossroads, as you say.”

And scientist Kate Moran goes further:

“To build a pipeline across the across the mountains, it is really expensive, so it doesn’t make any sense. It doesn’t make any economic sense. We need to turn the page. Canada has the ability to provide renewable energy as an export. We know that DC cables can transmit electricity far, very far. So building our renewable power to produce goods take our natural resources to produce goods and export them sustainably. Advocating for more oil exports is short sighted and not sustainable.

So, there you have it. Two choices. One intersection. Which is the better road forward?

Sam Sullivan is a seasoned politician and he says “the best answer I’ve ever heard is: ‘It depends.’”

Sam, the former mayor of Vancouver and a former BC cabinet minister, has spent his life juggling chicken-or-the-egg questions like this one.

“I think everybody wants to have a healthy environment, but there’s just different opinions as to how we weight each of those goals.”

Indeed. And we need to really listen to the diverse opinions of our neighbours if we’re to make the right choice at the crossroads we’re facing as a nation.

“Specifically for indigenous communities, it was from the earth that communities were able to thrive. That is the same for non Indigenous communities as well. So we need to be thinking critically about how we want to interact with the earth. What values are important to us? What do we need to protect? Where do we need to give, and what kind of a world are we comfortable leaving for the next generation? Because those are not just indigenous conversations, but conversations that everybody needs to be having right now.” – Libby Garg | Indigenous Judicial Judge and Entrepreneur

“What we have to do is find a balance, and I think both the environmental movement and the energy industry and the hard core advocates will have to recognize that both sides have valid, valid concerns.” – Erin O’Toole | Former Leader of the Conservative Party

But remember what we discussed earlier? We’re only hearing these valid and important opinions through the prism of our worldview.

So, let’s check our biases and really understand the two roads that meet at this intersection.

Canada is rich in natural resources, obviously. We all understand, at least at a basic level, that developing our natural resources equates to jobs and, in some cases, the very existence of a community. But how well do we actually know the industry?

“Even here in Alberta, people don’t really understand the benefit of the resource industry.”

Hal Kvisle is the former CEO of Trans-Canada Pipelines and is considered one of the energy industry’s leading voices.

“If you think about where Alberta is today, with 4 million people, and compare that to the provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba – both of which were quite a bit bigger in population terms than Alberta 85 years ago – you can see that the reason this place has thrived and prospered is the development of energy resources.”

Hal says that impact has allowed Alberta to create the second largest pool of skilled workers on the planet. And he believes that means “we’re so much better equipped today than we were 50 years ago to actually generate significant economic value without being harmful to the environment.”

But a successful resource industry is about more than innovation. As Hal explains:

“The royalties that the oil companies pay go into provincial coffers and pay for schools and hospitals and things like that.”

It’s true. The resource extraction industry does pay for a fair number of hospitals and schools and roads, but they pay for a lot more than that.

Why?

Because the resource industry in Canada pays governments, on average, $14.8 billion per year in tax and royalties. And while that is down from the $21.4 billion paid in years gone by, it’s still a very big number.

But as big as this number: $377-422 billion dollars. That’s how much the resource industry contributes to Canada’s total exports and, if you haven’t already heard, that’s pretty important to a trading nation like Canada.

You see, raw resource exports don’t require us to import additional materials to make a final product for export. That means our resource exports have incredible value. It’s a major reason why the resource industry accounts for almost one-fifth of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product – the most commonly used metric to determine the health of our economy. And a healthy economy? It’s about more than balance sheets, helping determine things like credit scores which really help when the country needs to borrow money in a time of crisis. Like the one we’re facing!

“But that’s only the tip of the iceberg.”

“But that’s only the tip of the iceberg.”

Hal Kvisle is right. 21 million Canadians are employed in a given year, and almost two million of those jobs – directly or indirectly – stem from the resource industry.

“The real benefit is in the high-quality employment that these companies offer their employees. The very interesting work that these people do.”

That is nice, but so too is this:

“The very significant income taxes that those individuals pay.”

Why is that important? Heather Scoffield explains.

“How do we pay as a society, for the hospitals and the schools and the and the arenas and the everyday amenities that we all share? We pay for it through taxes, and we only pay taxes if we’ve got work to do.”

In other words, for all of the value the resource industry provides our country in terms of taxes paid and GDP value created and donations to social causes offered, it all pales in comparison to the tax revenue our governments generate from workers in the resource industry. As Hal says:

“It’s really much more of the money that flows through the employees towards the Government of Canada (than what resource companies pay directly in tax). That’s a much bigger fish.”

It is. Because a robust tax base? That’s helps us sustain our environment. After all, the largest funder of conservation in Canada? You guessed it: the Government.

Now, it’s true, biodiversity is in decline in Canada and it’s also true that, because of our boreal forest, Canada can be a global leader in halting biodiversity loss. And, yes, many of our resource development opportunities can be found in that same boreal forest. But resource development, in the traditional sense, isn’t the largest driver of biodiversity loss in Canada – that distinction goes to agriculture or human food production, though housing – in cities and rural communities – shouldn’t get off that easy either.

And though the real estate and agricultural industries help pay for parks and restoration and endangered species protection – through tax and that paid by its employees – they don’t pay as much of the tab as the resource industry.

Which means the resource industry isn’t just important to our economy, but to our conservation efforts as well.

And then there’s this:

“The reality is that a certain amount of climate change has already happened. And there’s another reality too, which is that the world still demands a lot of fossil fuels, and we have them. We can get to far in the conversation, there’s a very productive talk to have about, yes, if we’re going to produce fossil fuels, what are we going to do to make sure that they actually create as few emissions as possible?”

Economics expert Heather Scoffield is right and she says this could be a huge opportunity for Canada.

“It’s a pretty exciting area for Canada because we are confronted with this problem all the time, it actually spurs on a lot of research. The biggest solution on the table is carbon capture, utilization and storage. Can we deploy it at scale? How are we going to pay for it? How soon can we get it up and running? That’s a very interesting, productive conversation.”

And while some demand nothing short of this:

“We really need to start thinking about how we can help create and support new economies for people who are working in resource extractive industries that are really doing injustices. And this isn’t to say that I’m anti jobs. I’m really advocating for a just transition.” – Sierra Daken-Kuiper | Cultural Anthropologist

Former federal Conservative cabinet minister Monte Solberg argues:

“I do think there is a pathway open to ensuring that we can produce energy and at the same time reduce emissions. And I would say something approaching a consensus around, for instance, export liquefied natural gas, while it can be argued it contributes to overall climate change, it can also be argued that it really reduces carbon emissions by supplanting energy sources like coal in India and other places in Asia that still rely heavily on coal. So I’d rather make progress as we go than throw a lot of money at different solutions and find out they don’t work and continue yelling at each other and find out that we’re getting nowhere.”

And if the goal is to go somewhere new, we will need money to invest in emerging industries, adds angel investor and tech entrepreneur Randall Howard.

“Canada needs to have more capital for these early stage businesses that will allow us to transform our economy.”

That capital investment? Former Conservative leader Erin O’Toole suggests it could come from resource revenues – so long as we don’t abandon the industry.

“We have for the next decade, decade and a half, oil and gas still being consumed in huge quantities around the world. Can we take some of the revenues from that and build out the electrification economy? Take coal out of all of the Canadian electricity grid like Ontario did with nuclear, that still ranks as the biggest emission reduction success story in Canadian history. But that takes money to build new generation.”

Money the resource industry can provide. And as Heather Scoffield adds:

“Strengthening Canada’s competitive advantage and building up our economy, it’s not just a pipeline. There are many other areas that we have potential in. And you know, some of them are around natural resources. It’s around critical minerals and trying to build the clean technology of the future.”

Right – critical minerals. Because even if developing them might hurt some aspects of the environment, not developing them might hurt us a lot more.

“When we talk resources, critical minerals, uranium we are also about electrifying building EVs. These projects will help decarbonize the electricity grid by getting more emission free energy on we should work with the United States on this, we should decarbonize the North American grid together – more hydro electricity from Quebec, from Ontario, from Manitoba, from British Columbia, and more nuclear uranium from Saskatchewan.”

For all of these reasons, Erin O’Toole says:

“We’re going to have to have an energy transition that is smart. A Smart Energy Transition is a timeline, and on that timeline, you have to use the benefit we have from our abundance of traditional forms of energy and build up capacity to decarbonize in a way that’s fair, and build up from the revenues from charging stations and new small modular reactors, so that on that timeline, we can phase out higher emission sources, we can work on biodiversity.”

So, that’s why the resource industry matters to our economy, and why it also matters to the environment. So, choosing this road is a no brainer, right? Well, not so fast, says scientist Dr. Kate Moran. She believes that the urgency of the environmental issues we face demands that we take this road instead. But this road looks slow and we need to move fast. Can this road actually deliver fast results?

“World War Two? World War Two is my answer. We can move fast. You know how many factories are built in the US when they declare declared war in World War Two, it was months.”

Do we need to move faster? Do we need to take a different road? Scientist Brian Menounos tells us:

“There’s a clear connection between rising air temperatures and rising greenhouse gas emissions. There’s not much dispute there. Should Canadians be alarmed? They should be concerned. They should be concerned about changes in natural resources. The reality is that projected climate change will impact many of these systems, but will also affect many areas of infrastructure and economic growth simply because of the consequences of damage caused by intense precipitation events. For example, those are factors that have to be taken into account.”

“There’s a clear connection between rising air temperatures and rising greenhouse gas emissions. There’s not much dispute there. Should Canadians be alarmed? They should be concerned. They should be concerned about changes in natural resources. The reality is that projected climate change will impact many of these systems, but will also affect many areas of infrastructure and economic growth simply because of the consequences of damage caused by intense precipitation events. For example, those are factors that have to be taken into account.”

In other words, given the importance of natural resources to our economy – given the potential impact of environmental problems on natural resources and our economy – we should consider prioritizing the environment for the sake of the economy.

Liberal MP Dr. Will Greaves adds:

“Once you go through with the project, be it a mine, be it a new pipeline project, you know that project goes through, and then it exists, and then all of the consequences and the potential negative impacts have to be dealt with indefinitely. Whereas, when an environmental movement or party wins a public policy victory, it’s temporary because it can always be revisited. It can always be reversed down the road.”

It’s a view shared, interestingly, by business leader Jimmy Pattison.

“We know more about the world and the earth and the atmosphere and with more population in the world, it’s important that we pay a lot of attention to the environment.”

Jimmy is one of the world’s most successful entrepreneurs.

“I don’t think that’s correct, but we’re working on it.”

How? In part, forestry and fishing – industries that impact the environment, but also industries impacted by the environment. And that’s why, Jimmy tells us, to grow our economy, we need to prioritize nature.

Why?

“It’s the right thing to do.”

For nature, but also?

“I think it’s good business.”

It’s why this debate, Jimmy believes, is simple.

“This is mother nature! We’ve been given a wonderful asset and we have to look after it.”

“This is mother nature! We’ve been given a wonderful asset and we have to look after it.”

And the key word there is asset.

Nature gives us life of course, but it also gives many of us our livelihoods. After all, the resource industry is nothing without nature – in fact, very few industries can withstand ecological loss.

How so? Well, again, consider your classroom and the river it helps steward: the mighty Fraser.

The Fraser – like all major river systems across this country – is massively important. It’s a food-producing resource, an economic engine and a vital transportation route for cultures since time immemorial. Today, in addition to the river basin being home to two-thirds of Canada’s third most populous province, it’s also responsible for 80% of the GDP of one of Canada’s richest regions.

It’s why river systems are amongst the most important pieces of infrastructure in our society. Highways and railways and buildings are nice, but not many of those infrastructure investments yield trillions of dollars in value.

Don’t believe me? Well, for starters, the Fraser and the other 24 major river systems in Canada supply one-fifth of the world’s clean water supply.

Don’t believe me? Well, for starters, the Fraser and the other 24 major river systems in Canada supply one-fifth of the world’s clean water supply.

That’s priceless, of course, but in actual dollar terms? The Fraser River alone provides $190 billion dollars in economic value – equivalent of 80% of BC’s GDP and 10% of Canada’s.

Canada’s largest river system – the Deh Cho or Mackenzie – is valued at almost $450 billion per year, more than 10 times the economic value of neighbouring industries, namely the oil sands.

And both these river systems – along with so many others – are the lifeblood of communities all along their banks, and along our vast ocean shoreline. How so? Quinn Scott explains.

“You think about how much money the recreational chinook salmon fishery alone (generates) – it’s a one-billion-dollar industry. That’s just recreational fisheries. Just for chinook. One billion dollar-a-year industry.”

Quinn is a professional fisherman, but he’s worried for his job and what the loss of this industry might mean to cultures, economies and nature.

“It’s not a huge scope that I have. There have been people who have been fishing the systems I’ve been fishing for 50 years. I can’t even imagine seeing it like (it was). It’s only been 15 (years) for me, and it’s brutal. It’s dark.”

Why is the economic future dark for fisheries? According to Quinn, it’s because of other economic choices we’ve made.

“Forestry is one of the absolute biggest causes of our (salmon) stocks declining.”

Forestry along the Fraser, to be exact. But is Quinn just picking on one industry – one livelihood – to save his own? He says no.

“We could drop the axe on commercial fishing. We could say no more for a full cycle, a six-year cycle. (But) we can’t just immediately shotgun, emergency fix the damage that’s been done (by) logging. The way a river looks after its headwater have been logged? It ruins it. It becomes, essentially, a chute.”

What does that mean? Quinn says “a root structure under a hundred-year-old tree on the side of a river somewhere up in the mountains is holding together the side of the mountain. We start clear-cutting all that stuff away and suddenly the natural, heavy rainfall is no longer natural. It becomes detrimental. It becomes fatal.”

What does that mean? Quinn says “a root structure under a hundred-year-old tree on the side of a river somewhere up in the mountains is holding together the side of the mountain. We start clear-cutting all that stuff away and suddenly the natural, heavy rainfall is no longer natural. It becomes detrimental. It becomes fatal.”

Not just for salmon or those who rely on the fishing industry.

If you’ve been paying attention to the news in the last few years, you might know how far reaching the economic consequences of floods truly can be – especially in BC, especially along the Fraser River.

And as Quinn argues, all the tree planting and restoration efforts in the world can’t address the root of the problem.

“The issue with logging (and) forestry practices throughout history – and why it makes such a difference now – is you can’t plant a hundred-year-old tree.”

And though those hundred-year-old trees might matter to fish and fishers, they also matter to the logging industry. The massive trees that grow on Canada’s west coast and in the inland rainforests near Mount Robson are amongst the most profitable type of tree to logging companies.

The tree’s ability to grow so old and so big? Salmon! And they – thanks to bears that transport them to the forest floor – feed the trees, as decomposing salmon provide the nutrients for tree growth.

That means as the salmon go, so too may go many of the profitable forests in the Fraser Basin. And that’s an issue, but not the only issue facing the logging industry, as Art Carson explains.

“It’s a very, very complex issue dealing with a forest.”

Art should know. He’s a professional forester who worked with the BC Forest Service and doubles as the Robson Valley’s local historian.

Despite criticisms that the forest industry has impacted salmon populations and the economy in the process, Art believes the forest industry has “always been a little bit better, I think, than the public sometimes thinks.”

But good or bad, Art Carson tells us the forest industry “won’t be quite the massive scale that it was.”

Because of declining salmon? No, Art fears for the future of the logging industry in the Fraser Basin because of the consequences of the pine beetle infestation.

Biologist Laura Kennedy has researched the pine beetle issue and says “once the problem began, I don’t know that there was a way to actually control it.”

Why? Well, for decades we suppressed naturally reoccurring fires to help our economy – forestry and tourism. But fires are actually a good thing – they help regenerate forests and control beetle populations, which exist to regenerate smaller stands of unhealthy trees. When we suppressed fires, the beetle population exploded.

The other failsafe that long kept the beetle population in check – cold winters – also started becoming less frequent.

With warmer winters and fewer fires, the pine beetle spread across 18 million hectares. That’s more than the size of 25 million soccer pitches and over 60% of the Fraser Basin’s total forested landscape.

The consequence was vast and far-reaching: The logging industry and communities that rely on the industry were thrown into disarray, with many communities and companies struggling to this day.

The dead trees, combined with salvage logging put into service to mitigate the new threat of super fires, like the one that devastated the community of Jasper in 2024, mean that peak water flows, say after spring melt, are now 92% higher than before the pine beetle infestation. The consequence? Floods and lots of them.

Though the pine beetle has peaked in BC, it appears to be marching – and blowing with the wind, thanks to increasingly challenging weather – into the boreal forest proper, increasing the risk of super fires, as we keep seeing every summer, turning carbon sinks into carbon emitters.

Laura Kennedy tells us: “If all of that forested area burns off, you’re going to have mudslides and the water retention is going to be different. And that’s going to change the entire ecosystem.”

In fact, long-serving BC cabinet minister Mike Farnworth told us the pine beetle’s economic toll has helped illustrate “a better understanding and a greater realization that climate change isn’t just about the earth warming. It is about the impacts that that has. It allows situations such as the pine beetle to happen because we don’t get those cold winters anymore that would kill the larvae.”

For all of these reasons, the United Nations’ David Cooper argues we need to prioritize nature. Otherwise?

“That will undermine our socio-economic goals.”

After all, biodiversity is the foundation of life on earth. A diversity of species is what allows for pollination and food security, water filtration and purification, waste management and pollution mitigation, not to mention carbon storage. We can’t afford, in every sense of the word, to live without biodiversity.

But as David explains:

“We can devote certain areas where we prioritize the conservation of biodiversity, but in doing so, we must make sure that we protect the most important areas for biodiversity.”

What does David mean? Take it away, Liberal MP Dr. Will Greaves:

“One of the ironies of Canada and Canadian public life is that the country is so huge and has such vast expanses of wilderness and natural beauty that it has led to a sense on the part of many Canadians, that we have so much nature that we don’t need to be as attentive to it, that we don’t necessarily need to be as concerned with some local environmental impacts of this project or that project, because there’s so much nature out there. That myth is one that I think we need to really be rid of.”

You see, because Canada is so vast and because we think we have so much nature, sometimes we prioritize protecting areas that need saving, but sometimes we don’t. Sometimes we assume development is fine in so much as there will always be somewhere else we can protect.

And while that calculation might be mostly true, it’s not always true. And as biodiversity expert Harvey Locke explains, like the economy, half measures don’t always work.

“Recent scientific assessment by the IPBES (The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) says we’re in a crisis and we need transformative change. “We really need to protect half the world in an interconnected way. That’s really what the numbers are.”

The key here is interconnected. Take your classroom.

“The entire (Rocky Mountain parks) complex constitutes one of the world’s greatest assemblages of protected areas and the aggregate is the size of the entire country of Switzerland.”

This matters.

“The Rocky Mountain parks together have a viable population of grizzly bears. The Rocky Mountain parks individually do not.”

“The Rocky Mountain parks together have a viable population of grizzly bears. The Rocky Mountain parks individually do not.”

In other words, because we went all-in on the conservation of this area?

“You have this full assemblage of large mammals, including the large carnivores, which are the hardest things to keep. Without parks, we wouldn’t have these species alive still.”

But remember, saving biodiversity is bigger than just saving grizzly bears in the Rocky Mountains. Saving biodiversity means protecting species big and small – species convenient and inconvenient.

“The reason we have large mammals left in the world is because of parks full stop period. It would not be here if we hadn’t made conscious efforts to protect muskoxen, white rhinoceros, an orangutan, grizzly bears, bison in parts, we wouldn’t have them now. Those are just cold facts.”

Which is why engineer and financial executive Sandra Odendahl argues:

“To understand the world around you at a basic level, to understand the changes happening in the world around you, the implications – I think a basic understanding of that is really important to everyone. Because we’re a wholly owned subsidiary of planet Earth, you have to understand the spaceship that you’re on. Even if you don’t know how to work all the controls, you should have a basic understanding of how it works.”

And how it works? Ecosystem services? They’re worth upwards of $179 trillion dollars – American – per year to the global economy.

That’s trillion. With a ‘T’.

To protect those services? It will cost the world a relatively small $200 billion per year. If we act fast.

If we don’t and yet want to safeguard the sweet, sweet economic value of those ecosystem services? The price will rise to $900 billion per year.

What does this mean for Canada? Well, remember the grizzly bear?

“When you look at a grizzly bear and you protect the habitat of that one grizzly bear, you’re actually protecting the habitat of all the other species that it comes into contact with too. You’re helping what it eats, what it preys on, what it defends from its territory – the wolves, the ravens – everything that it works in co-existence with.”

Biologist Sarah Ramirez is right. In some circumstances, by taking urgent action to enhance protection for a species like the grizzly bear – already relatively well protected – we can actually bring down the overall cost of biodiversity conservation because we get such great bang for our buck – and because our chances of success are high.

But in the case of the caribou?

“All caribou are actually endangered across every sub species.”

“All caribou are actually endangered across every sub species.”

Stephanie Leonard and Nikita Lattery are with Caribou Patrol, an Indigenous-led stewardship program that works along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. And as they tell us:

“The landscape, the environment is out of balance. It’s something is out there that is causing an imbalance to the system, and the caribou are the warning sign. There isn’t another animal out there that can take the caribou’s place.”

In other words, without fast action, we might lose the caribou. Does it matter?

As financial executive Sandra Odendahl says: “that’s not just a scientific question. I worry that the other people who should be weighing in and thinking about that and debating those decisions… I don’t know if everyone is equipped to have those conversations because they are disassociated from nature.”

That’s a problem and so too is this:

“That’s a problem, this lack of connection. Just we just don’t see how the pieces fit together.”

Ethicist Dr. Kerry Bowman is right, and as he adds:

“There could be cascade effects with biodiversity. We have a very high level of loss, and it’s escalating very, very quickly. We don’t even know what could be triggered.”

Look, with both options – both roads – there is risk.

How much risk are we, as a nation, willing to accommodate at a moment like this? Economically or environmentally? The answer likely depends on where we live, how we might be impacted, and how well we understand the issues.

In other words, there won’t be one simple answer.

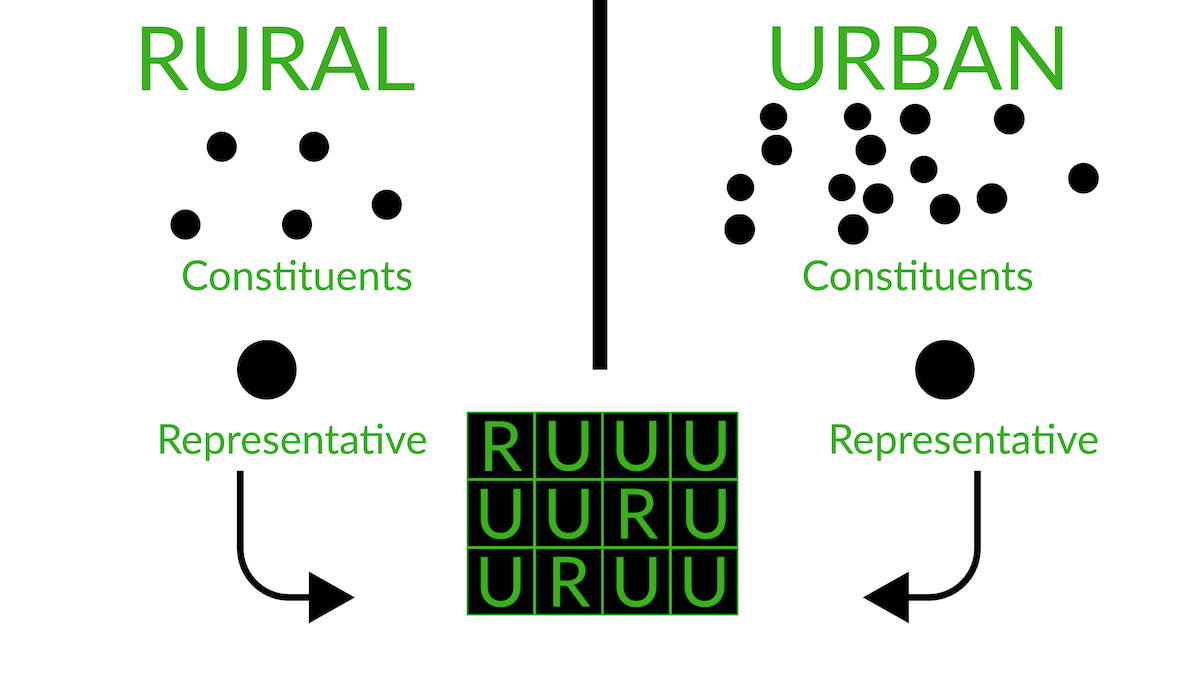

This is why we have demarcation lines all across our society. But the most pronounced, at least on this question? The urban-rural divide.

Of course, the urban-rural divide isn’t new. It started in about 1900 when cities started becoming a thing, but it’s growing and has never been more pronounced than it is right now, as pollster Shachi Kurl reminds us.

“That is now framing and reframing almost every facet and part of Canadian policy and societal debate.”

How so? We asked rural advocate Joel McKay.

He told us, quote, “what’s needed…is a society in which every Canadian can succeed…that means access to proper education, healthcare, social services, a job market with robust opportunities. These things can only exist in rural areas if we have a landscape that’s attractive to business development and investment, which generates the needed tax revenue to support the social services that support healthy development of our children into adults. That means we need an environment that supports resource extraction, attracts investment and leverages the benefits generated from that to reinvest in rural areas so that they have just as much opportunity as our urban areas.”

In other words, by choosing one road over another at this crossroads? We risk dividing our nation. And when it comes to decisions like this one?

Joel says, quote: “Rural B.C. has very little to say where it concerns provincial elections, much less than federal ones. Unlike other jurisdictions, Canada does not have a proportionate electoral system, business environment or taxation regime that recognizes the outside value rural areas generate for the rest of the country.”

Joel says, quote: “Rural B.C. has very little to say where it concerns provincial elections, much less than federal ones. Unlike other jurisdictions, Canada does not have a proportionate electoral system, business environment or taxation regime that recognizes the outside value rural areas generate for the rest of the country.”

Political Science professor turned Liberal MP Dr. Will Greaves agrees Canada’s electoral system isn’t proportional, but says that’s to the benefit of rural communities and their advocates.

“Actors who are, maybe, relatively minor within our system can still be veto players. Under the right circumstances, the mayor of Montreal or the mayor of Vancouver, or the premier of one province or another, or as has been the case in Canadian history, even a single legislator in a single provincial legislature, can have the power to fundamentally alter the course of the country’s history.”

And social scientist Dr. Victoria Lukasik says that her research on environmental policy suggests it’s actually rural communities that have the most power in our electoral system.

“Especially in Western Canada, our vote is really affected by the rural population more so than the urban population.”

Who’s right? Well, in truth, they all are.

Rural communities have less of a say in provincial and national matters than those who live in urban centres because urbanites are the significantly larger demographic in Canada – they represent more than 80% of the Canadian population. Yet urbanites are significantly underrepresented in Canada’s first-part-the-post electoral system.

As Michael Pal of the University of Ottawa explained to CBC Radio, quote, “your vote in Labrador is probably worth three and a half times more than a vote in Vancouver. So, it’s as if we said everybody in Labrador gets three and a half ballots, and everybody in Vancouver gets one.”

And there are countless examples of urban ridings that have populations in the hundreds of thousands and rural ridings with populations in the tens of thousands.

Michael Pal added to CBC, quote, “The least powerful voter in Canada is probably a recent immigrant from Pakistan, Bangladesh, India or China, who lives in Brampton, Markham or Mississauga – places where population is growing very quickly. So that tends to be the suburbs around the biggest cities. So, it’s not necessarily downtown Toronto, but it’s the 905 area code (the suburbs around Toronto).”

In our system, it’s easier for specific issues in rural ridings to be addressed. Think about it:

Rural constituents have fewer voices to battle to get the attention of their elected representative. And given that a rural representative has fewer constituents and fewer issues to juggle, they, in turn, can be effective advocates in government or opposition.

It’s why strong opposition to a park proposal in one rural riding can kill the planned park outright. After all, park proposals in one part of the country are rarely the top issue for a majority of voters in enough urban ridings to counter the focused, political advocate for the one riding where opposition is strongest.

Make sense? Good. Here’s the flip side.

Broad, less-specific policies – say, environmental regulations like a tanker ban – usually can succeed in the face of rural opposition, even if the urban vote is more diluted.

In this case, a broad policy might be the top issue for enough voters in enough urban ridings. And if way more people in way more ridings contact their representatives about one policy, then the urban representatives will be united on the issue. And given that there are more urban ridings than rural ridings, a majority of urban elected representatives can overrule the majority of rural representatives.

It’s an imperfect system without a perfect alternative.

Division of any kind – but especially the urban-rural divide – threatens to further complicate an incredibly difficult decision. And that’s especially true when the goal is to balance majority will and minority rights – and minority rights of one segment of the population against the rights of other minority populations.

Division of any kind – but especially the urban-rural divide – threatens to further complicate an incredibly difficult decision. And that’s especially true when the goal is to balance majority will and minority rights – and minority rights of one segment of the population against the rights of other minority populations.

And almost every decision impacts someone’s bottom line – their culture, their beliefs, their livelihood, their sense of justice, their – our – environment.

“You’ve got to figure out how to come together more often. And I think in a way, we do separate ourselves quite quickly and put ourselves into silos or into categories or groups. I’m right wing, I’m left wing, I’m conservative, I’m liberal, I like cheese, I don’t like cheese.”

Pete Smith is an artist, as well as the founder of the Rural Centre for Arts and Creativity. He argues that even if we do like to separate ourselves into silos, the urban-rural divide?

“I think it’s in the mind. I don’t think it’s necessarily something that is physical.”

Which isn’t to say Pete dismisses the idea of societal divisions.

“There are a lot of folks who have points of view that are very, very strong, and they absolutely are not interested in any other point of view other than their own.”

And that’s the issue. For when we don’t listen, we often make faulty assumptions, as demographics expert Hamish Marshall explains.

“The divide is often not quite where you see it the real societal division.”

The real societal division? Hamish says:

“I think it comes down to the more of a divide around opportunity, that there’s a lot of places in rural Canada that don’t feel like there’s an awful lot of opportunity. Whereas, if you’re in a large city, even if you’re commuting in a long way, there might be an opportunity to work in interesting jobs that are for a variety of employers. That don’t exist in smaller communities. But there’s a lot of places on a spectrum in between, a lot of suburban places, some of increasing density, some that are low density and pretty ex urban – that is where that opinion divide comes. At various points in the past, we’ve actually found that the suburban areas have attitudes much more similar for rural areas, and then when, at other points in the last 10 years, suburban areas had a lot more similarities to the more densely urban areas.”

Which is a different take on an important issue. And that matters. Because when we move beyond assumptions, new realities – new opportunities – can emerge. It’s why, in a moment like this, Hamish urges us all to:

“Reject easy categories, when you look at the numbers as realizing that the world is anything but monolithic, that there’s an incredible amount of different perspectives, and different lives that everybody’s living. Understanding that is good for all of us.”

Pete Smith agrees that we must move beyond our assumed differences.

“In the same way I feel about rural folk, I feel about urban folk, I feel about the trees, the water and the stones. I think that we really have to start to broaden our definition of who we are, what we are, why we are. While I know there are divisions, I see the opportunity in people coming together. It’s these transferences, it’s sitting down at a kitchen table, it’s getting together and exploring differences together and having a conversation.

How do we accomplish this?

“The culture or the creativity that brings people together, and the creative part of your brain that gets lit up, not the part that’s kind of starting to get isolated and get into a silo. I believe that the cultural divide, whatever it might be anywhere, is being able to sit with another person and hear them tell a story. So I think the divide is actually crossed through listening. So when I sit at a kitchen table and listen to someone who stops judging me for what I am, what I look like, for who I am, where I come from, and everything else, and they start telling me a story. And in the story, then comes your heart. And when you’re actually serving that up, a vulnerability and innocence comes back into play. And when that comes up, then I think you’re in a position to really get into a meaningful conversation about what it is to be here.”

And what does it mean to be here – to be Canadian? Well, maybe it starts with agreeing on these fundamental truths:

And what does it mean to be here – to be Canadian? Well, maybe it starts with agreeing on these fundamental truths:

“The Chinese have a salutation: Have you had your bowl of rice today? If you haven’t, then you must eat before anything else. Somebody having a bite to eat is important. And I also think the ability to learn – through that learning is an ongoing curiosity about the world and realizing that you know nothing. As you learn and continue to learn, you realize that there’s so much more to learn. If we can get ourselves out of our own myopia, then how do we think about the little beings and then water and trees and actually handing the place over. Leave the campsite better than you found it was what my old man always said. Treat others the way you’d like to be treated. And those two tenants should be available all the time, regardless of disagreement.”

Pete’s right.

Before we can settle on a road forward for our nation, we must first reach a common understanding of our equally valid realities and challenges. We must listen to what makes us different so we can work together towards a Canada that unites.

“That needs to be a part of our education process. There’s a cultural divide there. Too often, some students are learning one thing and others are learning another. We’re tending to put people into these silos of thinking. If you can get to a place where, just because it’s different, it doesn’t make it weird. Too often we go, ‘oh, that’s just weird. I can’t imagine that’. No, it’s not weird, it’s just different. That lesson has been taught. There’s a French writer named Jean Marc Dalpé – one day, was talking to him about how every year, the group in France that gets together and decides which is feminine, which is masculine, the new words that are coming into the French language. I said, ‘isn’t that weird’? And he said, ‘No, Peter, it is not weird. It is just a different’.

In some ways, the cultural divide will be crossed when we stop looking at things as a threat to us but an opportunity to come together. I say all this stuff, and it’s idealistic, but if we don’t have a dream, if we don’t have a vision for what the future is beyond just fighting, then we’ll just continue to fight. And I don’t live that way. I’m not interested in living that way.