Be Better

Chapter Eight

“I think that it’s really important for everybody to express their beliefs.”

“I think that it’s really important for everybody to express their beliefs.”

Mary Young Leckie is one of Canada’s most celebrated storytellers, having produced countless award-winning productions on the screen and on the stage.

“If you think your own ideas are unpopular, you might keep them to yourself and they get so deeply ingrained when you keep them to yourself. And they turn into biases and sometimes they turn into bigotry and sometimes they turn into racism or classism. The more you keep that stuff inside and don’t share it, I think the more dangerous it is. So, if you bring those ideas of yours out into the open, have other people hear them, you may still believe the same thing at the end of the day, but you don’t become so entrenched that you can never move forward.”

That’s why we all need to be heard.

As the former mayor of Vancouver Sam Sullivan argues, “it’s so important that we bring controversial ideas into public discussion. And people don’t want to have those discussions, but I think people should be aware of them and people should engage with them. That’s the way we get better government.”

As the former mayor of Vancouver Sam Sullivan argues, “it’s so important that we bring controversial ideas into public discussion. And people don’t want to have those discussions, but I think people should be aware of them and people should engage with them. That’s the way we get better government.”

Sam’s right: It’s not popular to speak up; it’s not popular to voice opinions that are outside the mainstream.

As Mary Young Leckie tells us, “What happens is it becomes very personal very quickly. I had a difficult conversation with somebody at a dinner party last week, and they got really personal really fast. And when that happens, everybody gets defensive because you feel like you’re being under attack.”

Former Alberta cabinet minister and author Donna Kennedy-Glans agrees with Mary, saying personal attacks for voicing opinions “is a consequence, but I can’t give up on what I feel passionate about. I respect these people and I love them, but you have to understand I care as much about the issues as you do.”

That being said, as Sam Sullivan points out, the right to free speech has limits.

That being said, as Sam Sullivan points out, the right to free speech has limits.

“I understand that there can be a place where the conversations are disrespectful and go against a good conversation and good public dialogue. So, we need to be respectful. We need to have an environment where people can have tough discussions. So, there’s a careful line that has to be drawn.”

Absolutely. It is a fine line, but one we all need to understand and uphold. If we don’t – if try to muzzle contrary voices – we do more than sow the seeds of division, as farmer Takoda Coen argues.

“If we get into a situation where we start to demand that our governments enact laws to make certain things illegal, we can we actually run the risk of taking power away from individuals and putting into more of the hands of these structures that become really difficult to change in the future.”

Kelly King of the Indigenous-led TRACKS program adds, on an even more fundamental level, “it is important to recognize that disagreement also pushes us a lot further, when we have disagreements that allow conversations to happen that we’re usually not comfortable having.”

In other words, disagreement – as disheartening and as frustrating as it can be – is healthy and vital in a democratic society, especially when dissent is constructive and respectful.

But like the conversation – like listening – we’re losing the ability and space and, some argue, the comfort to disagree respectfully.

It’s why Mary Young Leckie laments: “I wish the listening skills – really truly listening to where people are coming from in your heart of hearts – was something that we practiced more. I don’t know how to do that. Well, I guess storytelling is how we do that, isn’t it?”

Ironically, Mary admits, as much as storytelling might be the solution, it also has played a role in creating the problem.

“Bias means conflict and conflict is good storytelling. So, you know, that’s kind of a tricky question. Because if I didn’t have conflict in my stories, they’d be boring as heck.”

True. But as Mary adds, “it’s framing it so it’s not personal. You’re not attacking a person for what they believe in. You’re perhaps having a go with their beliefs and trying to change them.”

But that works best when we avoid words that divide, when we consume media that encourages thoughtfulness, when we realize that good communication starts with conversations, with questions, with listening. And when we do all of that? Then, yes, we can and should speak out; we can and should add our story to the mix.

As Mary argues, “I think everybody should be creating their own story.”

But writer Ian Brown says to tell our own story, “You have to be able to tell the story well, just so that people will listen to you in this media blooded time.”

But writer Ian Brown says to tell our own story, “You have to be able to tell the story well, just so that people will listen to you in this media blooded time.”

So, what kind of story will help cut through the noise? Journalist Clive Jackson tell us: “If a dog bites a man, it’s not a story, but if a man bites a dog, that’s a story.”

And Clive really wants us to understand what is a good story so that we can tell ours effectively.

“A good story is something that basically nobody’s heard before. So, it’s new, it’s fresh, it’s different.

“To my mind, it is very simple: Can you imagine a story on television at night and you’re watching it and you think, ‘well, that’s a pretty cool story’. So, you go into work the next day, and you say to someone, ‘hey, did you see that story last night on television news? No. Well, let me tell you about it.’ To me, that’s a story that resonates – people talk about it.

Clive adds that “for any good story, more or less, you need real people. You want to get away from suits and ties and, I think, to some extent you want to get away from the politicians.”

Clive adds that “for any good story, more or less, you need real people. You want to get away from suits and ties and, I think, to some extent you want to get away from the politicians.”

But when topics are complex and require nuance and context and science even, it become harder to do that.

“That’s consistently the communications challenge that we have in the environmental sector,” explains environment storyteller Kyle Empringham.

But it’s not an impossible challenge if we learn the information and find a way to share it impactfully, as changemaker Marie-Eve Marchand argues.

“Never assume that people know something. That’s the first thing. People don’t have the time to learn (what you assume they should know). So, it’s your responsibility, when you want to make a change, to learn it for others and communicate your information simply.”

Conversations That Matter host Stu McNish agrees.

“If I want to tell nature stories? If I want to influence the way that people think about our relationship with nature? Then I have to keep talking about it. I have to go back; I have to find information; I have to figure out a way that I’m going to share that information so that people go: ‘Hmm. That’s cool. I didn’t know that.’ You then start to get them to think.”

“If I want to tell nature stories? If I want to influence the way that people think about our relationship with nature? Then I have to keep talking about it. I have to go back; I have to find information; I have to figure out a way that I’m going to share that information so that people go: ‘Hmm. That’s cool. I didn’t know that.’ You then start to get them to think.”

And making people go hmm – making them stop in their tracks and actually rethink what they know or don’t know, as the case might be – that’s the goal. But it’s a harder goal to accomplish in today’s media landscape, Stu believes.

“The style, the messaging, the focus, the types of delivery, the medium keeps changing. And, so, it becomes incumbent upon all of us, no matter what medium we’re in, to stay right on top of those changes. You can’t say: ‘Well, okay, there it is. I’m sticking with this.’ So, it takes experimentation to find something and then constantly revisiting and refining that.”

Producer Mary Young Leckie says we should embrace that reality as an incredible opportunity.

“There are museums opening up everywhere. There are storefront theatres popping up; you can do plays in a park. You can create a movie on your iPhone. There are huge opportunities.”

But some things haven’t and won’t change, says science writer Niki Wilson.

But some things haven’t and won’t change, says science writer Niki Wilson.

“People have a hard time taking in information when there is a lot of blame associated with it, a lot of guilt.”

And we don’t need to shame people into hearing our perspective or supporting our ideas, argues Ian Brown. We just need to have a good story, well told.

“Stories – whether they’re on TV, in print, wherever they are – they are made up of dialogue (people talking), scenes (time and space unified), point-of-view (which is the way people see the world) and details that are fascinating. If you start with those structural details, it doesn’t matter if you approach it from the individual point-of-view or from a grand point of view because the storytelling will solve all the problems.”

And Niki Wilson adds that “if you can do that in a way that isn’t alienating and really can bring people along as part of the experience, I think that’s all the better.”

Because people want to feel included in the stories we tell – the narratives society shapes.

And we all must have a place in our collective story.

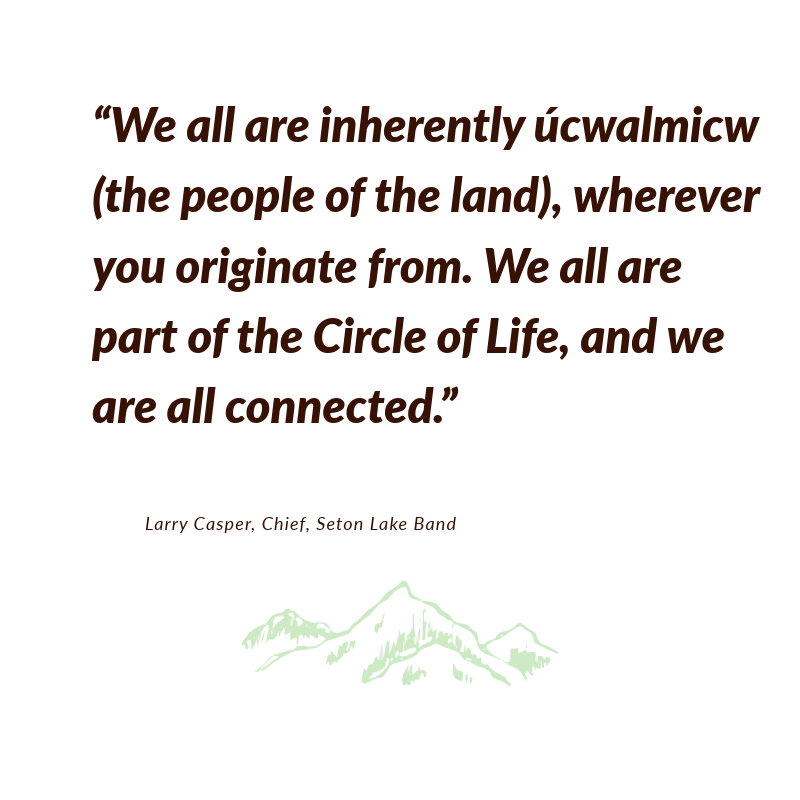

As Indigenous leader Larry Casper reminds us:

“We all are inherently úcwalmicw (the people of the land), wherever you originate from. We all are part of the Circle of Life, and we are all connected.”

But we lose that tether of common humanity when we talk at people, when we put people in boxes and tell them how they should think, when we thoughtlessly use terms like tar sands or foreign-funded radical and disrespect segments of our society, when we limit who we listen to: Our stories become propaganda, our discourse becomes divisive and the challenges we face get stuck.

No one wants to speak to a closed door. No one will listen to what we have to say if they assume we’re not open to hearing what someone else thinks.

Which is why good communication doesn’t begin where we might assume.

Good communication? It starts with each of us and our willingness to embrace our responsibilities as story-seekers and storytellers – just as it always has been, just as it always will be.