Here’s How

Chapter Five

By now, you understand systems – and how our system interconnects with the natural systems that sustain us all.

You get the importance of context and why it matters to go beyond your first question and find the better question.

And you now know that decision-making isn’t easy, but that creative problem solving can spark visual stories that lead to a better world.

But how to put all of this together? What’s the best process – the game plan, if you will – for helping a great visual story capture the world’s attention?

Good question!

To find the answer we asked Michelle Valberg, one of Canada’s most celebrated visual storytellers, to share with us her process from inspiration to impact.

“When I realized how little I knew about the arctic and about Canada’s north – about the people, about the landscape, and about the wildlife? That’s when I came back and I said, ‘I need to share this’.”

“When I realized how little I knew about the arctic and about Canada’s north – about the people, about the landscape, and about the wildlife? That’s when I came back and I said, ‘I need to share this’.”

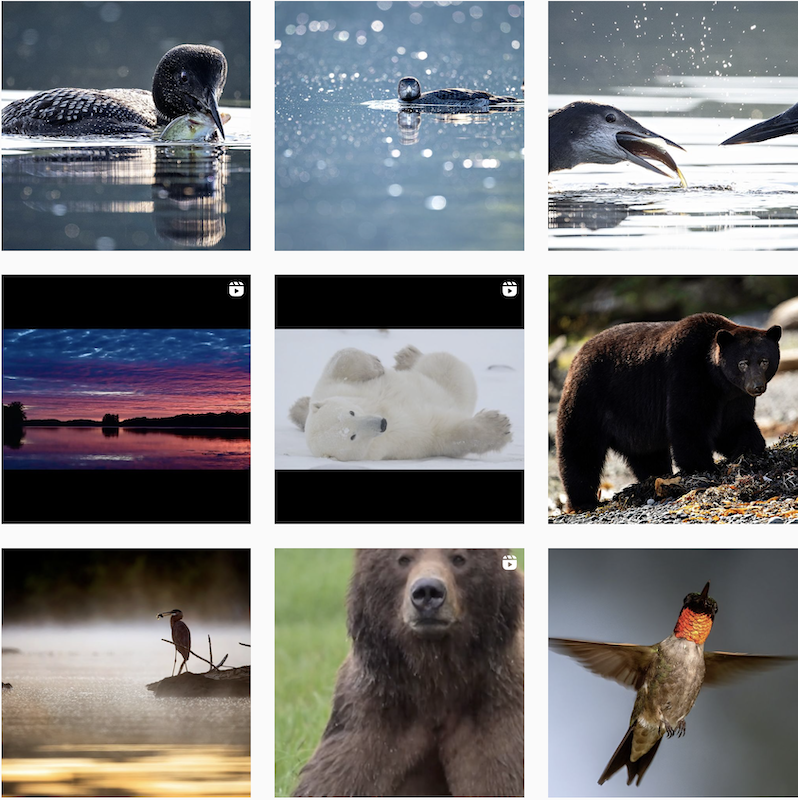

Michelle has been a visual storyteller since the first time she went for a walk in the woods with her father’s camera. But becoming one of the world’s most well-known photographers, with her work appearing in publications and galleries globally, wasn’t an easy process.

“I started by doing what I had to do to make a living – and that included the weddings and the bar mitzvahs and the events and the portraits. I did everything I could in photography just to make a living at it. So, for nature and wildlife to now be my primary source of photography, I had to build into that.”

But work at it she did and, according to Michelle, a big part of her growth – and sustained success – has been asking herself: “What makes a great nature and wildlife photographer? I’m searching for that answer, always.”

Why?

Because as technology changes – as trends come and go – the definition evolves.

“Mobile devices have opened the world of photography to so many people. So many more people are creating and visual storytelling, whether they know it or not, because every day they’re posting on Facebook, on Instagram, on social media and sharing their images with the world like they never have before.”

Which can be threatening, but only if we let it. That’s why Michelle says to be a creator in a changing world, we need to keep pushing and evolving our creative process.

“It’s just breaking those barriers and always pushing yourself to do more and to experience more and to create more.”

Michelle tells us that the one constant in her artistic process is being aware of not only what inspires her, but also what will inspire others to consume her work and her message.

“What’s that emotional connection? What’s that emotional impact that will stop people in their tracks when they’re going through their Instagram feed? What is the image that’s going to stop them in order for them to learn more? It’s that emotional connection that I think we can all relate to, and I try to find that in every image that I do with wildlife. Some sort of, either, eye-to-eye connection or that physical connection, mom and cub having an intimate moment. Those are the images that impact people the most and those are the images that you want them to stop at and learn more from.”

“What’s that emotional connection? What’s that emotional impact that will stop people in their tracks when they’re going through their Instagram feed? What is the image that’s going to stop them in order for them to learn more? It’s that emotional connection that I think we can all relate to, and I try to find that in every image that I do with wildlife. Some sort of, either, eye-to-eye connection or that physical connection, mom and cub having an intimate moment. Those are the images that impact people the most and those are the images that you want them to stop at and learn more from.”

And when it comes to inspiring an audience, Michelle says knowing when art should speak for itself and when we must speak for our art is a fine balance.

“There’s two sides. One – you can leave it. And sometimes it’s best left unsaid, leaving the viewer to create their own story and it becomes theirs. There’s times when you have a pretty powerful image that you can use more of your words and help translate it. But being truthful is what’s most important. I would never take an image and tell it otherwise, or embellish it. Stay truthful in order for it, hopefully, resonate and inspire change.”

How to follow in Michelle’s footsteps? Start here:

“What fuels you? What interests you? Is it a small mammal? Is it a large one? Is it a whale? Is it underwater? Is it tiny? Whatever it is – whatever messaging you want to do – believe in it, work it and really understand it. The more research that you do, the more information that you can get and arm yourself with, the more that you’re going to be productive in getting your messaging out. So, just believe and work really hard and understand and share with the world and it will all come together. And be truthful.”

Michelle adds, don’t underestimate the importance of “believing in yourself. Believing in your cause. Believing in your wildlife that you’re photographing. That’s the most important thing: Being true to yourself and your message. And if you do that as a photographer, as a writer, you’ll be miles ahead. It’s your truth. It’s your own passion. That’s what’s going to translate, and people will believe that. So, you have to believe in yourself. And if you believe in yourself? You’ll work hard, you’ll follow your passion and you will continue your storytelling.”

It’s for this reason that ocean storyteller and advocate Diz Glithero says, “Find your allies.”

It’s a lesson Diz has learned through her journey.

“If you’re someone who’s driven or goal oriented, it’s easy to sometimes just do it on your own. As I went on through life, (I saw value in) just building that community, that professional learning community, those allies.”

Kyle Empringham agrees. Why?

“The environmental movement is always going to have this very tough challenge of trying to articulate things. And sometimes you can see and hear (the issue), and many times you can’t.”

“The environmental movement is always going to have this very tough challenge of trying to articulate things. And sometimes you can see and hear (the issue), and many times you can’t.”

And while that might always be a challenge, Kyle says environmental storytelling is easier when we collaborate and find help.

“Make room for voices and opinions to be shared and heard.”

Kyle is a storyteller and co-founder of The Starfish, an online storytelling platform that seeks to find new ways to share and amplify the ideas of young environmental change-makers. The idea was the by-product of an awkward discovery, Kyle explains.

“I remember learning a lot about the scientific method and how science is created. And then I would go out to try to explain it to someone else and they would not understand anything I was saying.”

Kyle’s solution? The Starfish.

“Humans connect with humans. It’s why some of the best stories you see and hear are human-interest stories.”

By using different storytelling styles to celebrate the ingenuity of rising leaders from across the country, Kyle hopes to be able to communicate a message that would otherwise be lost in a straight-up environmental essay or campaign pamphlet.

“By doing that, we think there is a lot to learn.”

But Kyle couldn’t make The Starfish a reality on his own.

“It’s always so important to make sure you’re consistently looking at the way that you take in information, who you’re hearing from. Can you hear from a more diverse group of folks in order to make better decisions?”

For Kyle, the answer was yes and his efforts to collaborate have helped The Starfish excel. But it’s a lesson that we should heed as well.

And though collaboration can happen quickly, Kyle says, “Understanding that a slow-going movement is one that can be intentional about the way that it’s doing things. It can make mistakes and not have it completely collapse (the project) underneath it. I know there have been things that we’ve learned from and grown from because we took our time. And I think there’s no shame in doing that.”

In the doing, Kyle says, The Starfish is “being a little more intentional with the people that we hear from and how we get their voice into our organization – specifically on the rural-urban divide, which is kind of great.”

Equally great, Kyle argues, is when environmental stories connect to and advance the broader narratives of a common cause.

“When people are trying to do their own thing, and their own thing on their own because they think it’s just the best way to do it, instead of trying to move a common mission forward? That’s when I think we start getting to a place where we are being redundant in a way. I think if we all remember what the common goal is, and try to strive toward that, then I think we can succeed.”

Of course, not everyone views the mission as being the same; not everyone defines success in the same way. Sometimes visual storytellers, especially, can provoke new ideas for what balancing people and nature actually can or should look like.

But ocean advocate Diz Glithero says, even still, there is a community of allies that we need to uncover.

But ocean advocate Diz Glithero says, even still, there is a community of allies that we need to uncover.

“Allies appear in all shapes and forms and places. And by building that network – building that community of people who are doing things that really fire you up and are engaging with the issues in a way that you can relate to? That’s kind of your way in. You can’t eat the whole elephant, so choose your bite and then together you can start to really drive that bigger change.”

More than that, collaboration can help us do more with less, explains storyteller and founder of Waterlution, Karen Kun.

“Sometimes people need a bit more money to make things happen.”

She’s right. And collaboration can help address skill or credibility gaps that come up in every process.

Still, Karen argues, as important as collaboration is, recognize it has drawbacks.

“There’s so many nuanced parts to people’s personalities. There’s so many things you might not know. You might not know if that person communicates and lays all their cards on the table.”

Indeed, though there are many helpful tools that help drive better processes and, in turn, create better results, no tool is one-size-fits-all and nothing is perfect. For this reason, Karen says, “I think we live in a day and age where groups of people are more important than the individual, but the group can’t function if the individuals aren’t strong.”

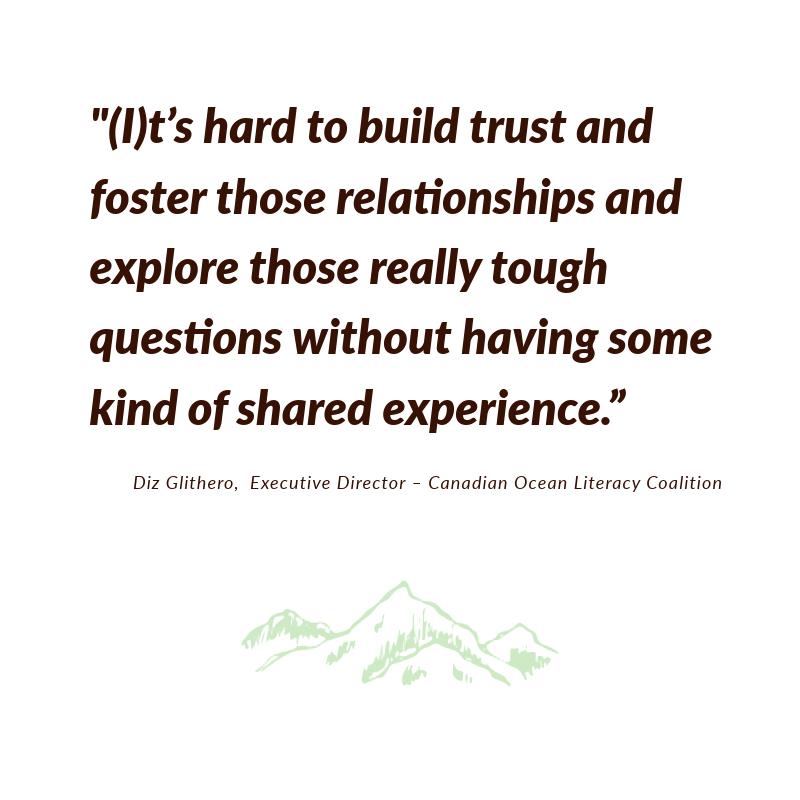

Diz Glithero understands the point and thinks that’s why successful collaboration comes down to trust-building.

“Part of it is, it’s hard to build trust and foster those relationships and explore those really tough questions without having some kind of shared experience.”

Diz adds that extends to art and story as well – it extends to the issues we want to tackle and the careers we want to pursue.

“The most powerful is when it’s the most personal. You can learn the science and the facts, but until you have a personal relationship with the issue, or the ideas, or the topic, it’s not relevant.”

Diz’s advice?

“It’s less about going to find that structured program or that structured agency to work with, but to spend time (having experiences and learning). We don’t do that a lot in today’s society. It’s go-go-go and it’s on to the next thing. I think to create space to just explore and create and share and learn with someone that’s in a medium or a space that resonates with them – it’s key. Because whether it’s through art, whether it’s through science, whether it’s through storytelling – whatever the medium is – there’s no one silver bullet. So, find other people who are involved in a space that ignites excitement for you.”

In seeing what others are doing, we can find inspiration; we can uncover ideas and processes to mimic and build on; we can identify partners and collaborators.

That’s how Brandon Nguyen went from using environmental research to increase awareness about biodiversity in his high school to uncovering an underused network of environmental clubs across Toronto that he felt could be repurposed to scale his impact.

That’s how Brandon Nguyen went from using environmental research to increase awareness about biodiversity in his high school to uncovering an underused network of environmental clubs across Toronto that he felt could be repurposed to scale his impact.

“Rather than starting something completely new, I just thought that there was a way to improve on the current system, which is creating this platform for students to collaborate.”

And, yet, in seeking input and in attempting to learn from recognized experts, youth leader and innovator Zeel Patel struggled to stay true to his vision that a new approach to medical science was needed to complement existing services.

“When it comes to creating start-ups and trying to find the funding and trying to really create real world change, there comes a point where there’s too many cooks in the kitchen. All of those cooks add various different perspectives, and sometimes those perspectives are contrary to what the original vision was. And I think it’s very scary if you concede to those perspectives and, in effect, dilute the vision you originally had.”

Good point.

There will be times when allies or collaborators will, without malice, mislead us. There will be times when we need to embrace processes that have been proven to work, and times when we need to create new ones that fit our ideas and our chosen path, whether it’s worn or not. And that’s why we need to heed this advice from Karen Kun:

“You can’t work as a team if you don’t know who you are.”

By knowing who they were and what they were doing and why they were doing it, Brandon and Zeel both were right in choosing different collaboration processes to advance their story and their ideas.

Indeed, it’s why two different artists can approach the same problem in different ways and get different results. And it’s why we need to remember two storytellers can tell the same story, but each through a different lens and, in the doing, convey different, important messages that might otherwise have been lost.