Hard Stuff is Hard

Chapter Four

“Often in the 21st century, you’re looking at very complex situations. So, it’s not ‘this is completely right’ and ‘this is completely wrong’, but in this difficult situation we find ourselves in, what is the best choice? And what would make it the best choice?”

When faced with impossible choices, many decision-makers turn to Dr. Kerry Bowman for help. He is, after all, Canada’s most celebrated ethicist.

An ethic-what-ist? An ethicist!

“Ethics is really an investigation into what would make something right, or what would make something wrong.”

Kerry has served as clinical ethicist at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital and is a professor of ethics at the University of Toronto.

As Kerry explains, “I try to illuminate what are the ethical options associated with this problem. I’m not an arbitrator. So, A versus B, I decide it’s B? That’s not what I’m going to do. I’m another voice to illuminate what the ethical questions might be.”

What kind of questions?

“A lot of my work has been medical and making decisions about when we should let go – and not just medical decisions – but family decisions about when we should let go and under what circumstance. What kind of life is worth saving, and what kind of life isn’t worth saving? This really pulled me into the world of ethics.”

Increasingly, Kerry isn’t just being asked to advise on medical questions, but also environmental questions.

“Increasingly, environmental ethics, conservation ethics is really beginning to emerge as the world and its challenges get more complicated. These things are really coming forward.”

“Increasingly, environmental ethics, conservation ethics is really beginning to emerge as the world and its challenges get more complicated. These things are really coming forward.”

And, as Kerry explains, the environmental questions we face are just as complex as the medical questions he’s wrestled with for decades.

“I have done medical ethics in a hospital, not all-around end-of-life, but a lot. Dying adults, dying babies for many, many years. And that’s been tough. But I’m finding environmental ethics just as tough. And I find the weight of the moral stress equally as difficult – almost more so with what I’m doing environmentally than with dying humans. And I don’t diminish from the reality of dying humans, I just think both things are huge.”

Why?

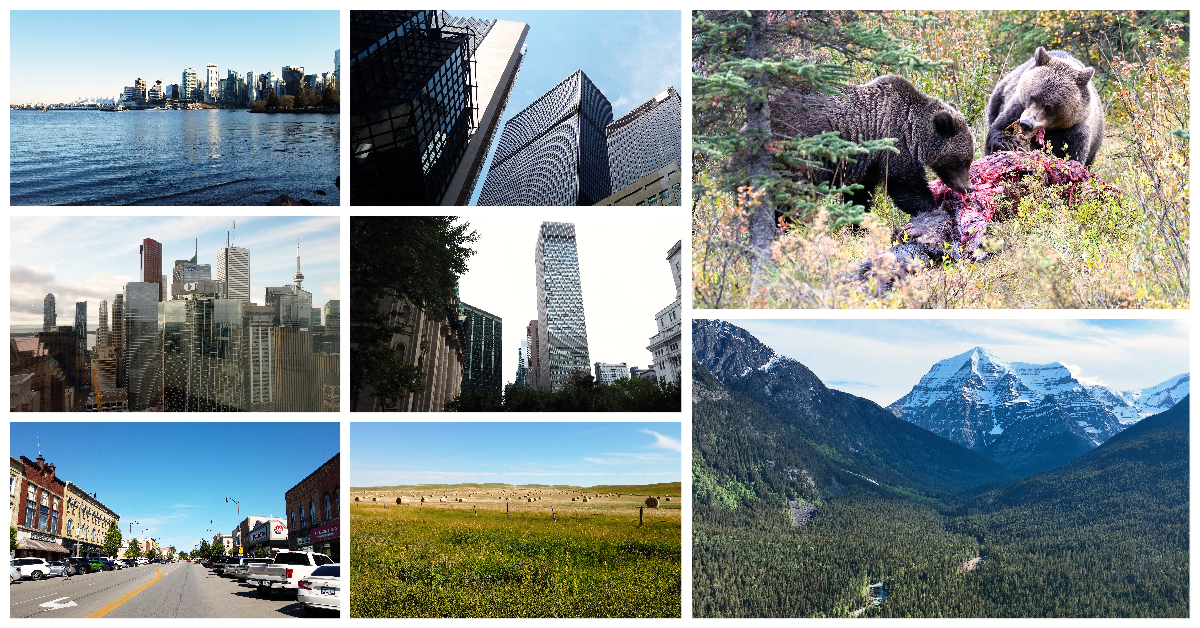

Well, as Kerry points out, “This is the only planet we’ve got. And from a scientific point of view, one of the things that gets lost here in the early 21st Century is the amount of knowledge that we’re picking up about space and what’s out there. All the various planets that we’re detecting. And what we’re seeing is everything, from our perspective so far, is dead. And then you have this one little jewel, which is the planet Earth, with this thin membrane around it, harbouring all this incredible life and biodiversity. And we’re poisoning it.”

According to Kerry, that simple fact often gets lost in decision-making processes because too few decision-makers – too few citizens – understand how nature works.

As Kerry reiterates, “This lack of connection? We just don’t see how the pieces fit together. At all.”

It’s why, when it comes to decisions big and small – personal and societal – Kerry argues, “We need that fundamental respect for biodiversity and nature. Because one of the reactions we see very often is: ‘So what? We’re just (worrying about) insects; it doesn’t matter. Well, it does matter.”

It’s why, when it comes to decisions big and small – personal and societal – Kerry argues, “We need that fundamental respect for biodiversity and nature. Because one of the reactions we see very often is: ‘So what? We’re just (worrying about) insects; it doesn’t matter. Well, it does matter.”

You’ve heard that before. But really listen to Kerry’s point.

“There could be cascade effects with biodiversity. We have a very high level of loss and it’s escalating very, very quickly. We don’t even know what could be triggered. It may not just be species lost here and species lost there, we may see cascading effects if this continues. But we do not understand what we don’t understand.”

And that’s, ultimately, the issue.

Our decision-making processes are not the construct of politicians, but a reflection of our society. And the majority of our society – whether they realize it or not – demand solutions that reconcile competing interests on compressed timelines.

Once again, Janet Austin, who served as BC Lieutenant Governor, reminds us:

“Often, we don’t recognize that what we’re asking for cannot be achieved in the short-term and may not, in fact, be possible. So, in some ways, we put decision-makers in an impossible box.”

In other words, we get frustrated with the differing and conflicting views of our peers – and we unleash that frustration on decision-makers, demanding that they find a way forward. Fast.

The result? If not indecision, then a rushed compromise. And though compromises are often lauded in Canada, better decisions aren’t necessarily born from compromise.

The result? If not indecision, then a rushed compromise. And though compromises are often lauded in Canada, better decisions aren’t necessarily born from compromise.

After all, one person’s compromise is another person’s sell-out. And often in a rush to the middle – in the hopes of quickly making everyone happy – the outcome is a watered-down solution that makes no one happy.

Do believe me? Check this out again:

“We have all this discussion right now about environmental regulations, and companies are going to get scared and not invest in Canada, but realistically environmental legislation is really weak in Canada.” – Dr. Victoria Lukasik | Biologist

“The amount of paperwork and process that occurs up front, that’s what I think Canada needs to take a look at. Because that’s what, in most of these big pipeline projects, costs more than $500 million and that just adds cost to the consumer at the end of the day.” – Hal Kvisle | Business Leader

“I understand that some people are operating under a certain global perspective about sustained economic growth and continued resource extraction, but when we look at the nuts and bolts of it, those things are just no longer sustainable in our current global reality. And it no longer becomes a cultural issue; it becomes a very practical issue about what we can and cannot sustain.” – Nikki Sanchez | Indigenous Media Maker

“An Alberta that’s not respected in Canada is deeply troubling to me. I don’t think we should just sit around and watch that. We need to talk about how that can be changed.” – Donna Kennedy-Glans | Author & Former Alberta Cabinet Minister

“Every time I saw someone talking about balance, what I really saw was the environment losing out.” – Cyril Kormos | Forest Researcher & Advocate

See? What we assume are obvious win-win solutions can, in fact, be seen as lose-lose outcomes.

Now, that said, just because compromises often leave too few seeing their needs met, doesn’t mean that balance doesn’t matter. It does. Very much so. And this is where creativity needs to come in, as Donna Kennedy-Glans explains.

“When you’re at the decision-making table, there are lots of times you make decisions where it’s not a black-and-white issue, it’s something in between. I’m not saying a compromise, or a lowest common denominator compromise, because I think we can do way better than that. But if you’re going to come up with solutions about how to make your parks better, it means you have to really understand the detail and the complexity and the options. If you take one option off the table, what does that mean for something else? It’s a give-and-take, but it’s also a better than.”

“When you’re at the decision-making table, there are lots of times you make decisions where it’s not a black-and-white issue, it’s something in between. I’m not saying a compromise, or a lowest common denominator compromise, because I think we can do way better than that. But if you’re going to come up with solutions about how to make your parks better, it means you have to really understand the detail and the complexity and the options. If you take one option off the table, what does that mean for something else? It’s a give-and-take, but it’s also a better than.”

If we take the time to do the right thing, the right way, for the right reasons, there is a chance we can find innovative solutions that allow different stakeholders to meet their bottom lines, without forcing everyone to the mushy middle.

Though as journalist Salimah Ebrahim cautions, sometimes innovative solutions are like a “digital solution being plugged into an analog government. We’re going to need governments in place that are open to these innovative ideas in the first place.”

Touché.

Innovation isn’t fast and sometimes we’re not fast enough to take advantage of innovation. And, at times, we pin our hopes and dreams on what we assume innovation will accomplish in the future, saving us from having to make a tough decision in the moment.

In other words, sometimes future innovation will save us and sometimes it won’t. And that brings us back to ethicist Dr. Kerry Bowman.

“There’s a lot on the horizon. There’s genetic editing, there’s cloning, there’s stem cell – there’s a lot of complex stuff. We want these ethical questions to evolve and mature alongside the environmental questions.”

Which is why Kerry says, “We have to ask as many questions as we can, but good ethics is based on good science.”

But science? It has its limits.

“‘Can we’ is the scientific question, and increasingly the answer is yes because we can do more and more. ‘Ought we’ is the ethical question. And that’s how the two things really need to fit together.”

So, what ought we do when faced with complex problems?

Kerry says, “These are tough questions, and environmental ethics is not just about having ethicists decide these things. It’s about working in communities and consensus-building. Talking to communities and seeing what they want to do and what the implications are.”

Kerry says, “These are tough questions, and environmental ethics is not just about having ethicists decide these things. It’s about working in communities and consensus-building. Talking to communities and seeing what they want to do and what the implications are.”

And as important as that is, Kerry wants to underscore this point:

“The risk with community involvement is that the voices of non-human life are not there either. So, we always have to be very careful because communities can say, ‘we’ll do this and we’ll do that’, but you’re still not factoring this multitude of species and biodiversity and the whole web of life.”

If we do consider biodiversity and non-human life in our decisions? Our choices become that much harder. Which is why, even though you’ll hear these next few quotes a few times across the Nature Labs platform, we really need to hear Kerry’s points again and again if we’re to understand the enormous complexity of the decisions we face.

“One of the things I’ve seen in Africa, is that people have said, ‘You Europeans, you cut down all your forests to make progress. Look at Britain! Britain used to be forested. Scotland was forested. You have nothing. And you’re telling us we can’t do this? We’re not allowed? This is wrong for us to do it, but you did it so that you could move forward. So, how can you say we can’t do it?’”

And then there’s this terrible dilemma, Kerry adds.

“You talk to Brazilians about protecting Indigenous territories and Indigenous people – you speak to people in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro about these things – and some people will say to you, ‘that’s not right, that’s not fair. I’m Brazilian too. I live in a favela (slum). I’m landless. I have nothing. Why should they have this, and why should that be protected, when I’m living in a state of poverty?’ And I don’t have a good answer for that. I don’t. I’m struggling with these things.”

And all of that must be weighed alongside this, Kerry continues.

And all of that must be weighed alongside this, Kerry continues.

“We don’t really understand the web of life. And we have to respect it. We wouldn’t be here if biodiversity and the web of life didn’t exist. This is what has supported us from an evolutionary point-of-view. This is why we’ve evolved and exist because of that web. And to see the destruction that we’re doing? Because that’s the web of life that’s holding us all together. And to see the destruction? It’s very problematic. But I think that’s why the ethics has to be woven in with the scientific inquiry.”

In other words, understand hard decisions are hard. After all, what we often assume is right, isn’t – what we often assume is possible, isn’t.

Kerry advise?

“A lot of ethics is about problem solving and one of the ways to problem solve is to listen. But if we become polarized, all of this is going to get a lot, lot worse. And we have to find common ground between ourselves and try and move forward in any way we can. Because once conflict begins, you’ve got A versus B and all this common ground between you is lost in the feud. That common ground is just gone, and often the answers are within that common ground.”

Kerry’s right.

We need to understand the difference between compromise and balance – and we must find the right balance between urgency and patience.

Even still?

Decisions won’t be easy, but make them, we must. After all, as Kerry reminds us, we’re all decision-makers.

“We need to encourage individual action. Individuals can do a lot. And when you have a younger person realize, ‘oh my god, I actually did that’, then they begin to see themselves a little bit differently. And then they (feel empowered to) do something else, and ‘wow, I did that too’. And slowly they can move forward. And as they move forward, they make connections with a lot of other like-minded people. And, so, it can move forward.”

“We need to encourage individual action. Individuals can do a lot. And when you have a younger person realize, ‘oh my god, I actually did that’, then they begin to see themselves a little bit differently. And then they (feel empowered to) do something else, and ‘wow, I did that too’. And slowly they can move forward. And as they move forward, they make connections with a lot of other like-minded people. And, so, it can move forward.”

Indeed, it can. Just as our two grizzly bear siblings taught us.

When we recognize our role as decision makers – in the science and research we learn from and advance, in the policy debates we engage with and help evolve, in the stories we tell and consume, within the careers we build and leverage – we understand our impact as stewards and citizens.

And when we get creative, while also being realistic? When we have empathy for those we disagree with and work to build relationships that can allow our ideas to thrive? We make better decisions for people and nature.

Even still, we must also understand that there are no guarantees that that every decision we make – as individuals or as a society – will satisfy every citizen or even every stakeholder.

But that reality? It can’t be an excuse for inaction. It can’t be an excuse to punt hard decisions.

Sometimes all we can do is act with good intention and move forward in the best way we can.

Sometimes all we can do is try our best and be brave.