Estimated Read Time: 43 minutes

Canada at a Crossroads

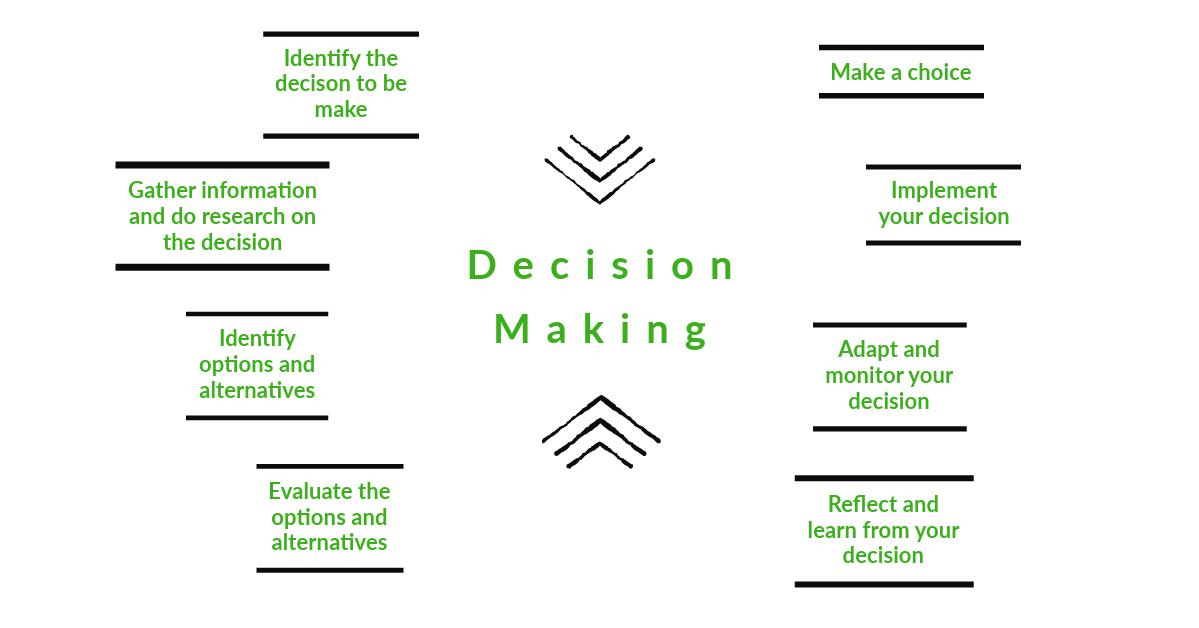

We know that systems are complex, that regional contexts are diverse, and that a shared identity is elusive. And all of this? It makes problem solving that much harder. But that can’t be an excuse for doing nothing. It can’t be an excuse for indecision.

We know that systems are complex, that regional contexts are diverse, and that a shared identity is elusive. And all of this? It makes problem solving that much harder. But that can’t be an excuse for doing nothing. It can’t be an excuse for indecision.

You see, in many ways, not choosing a way forward – not being definitive – is what has allowed our challenges to become so intractable.

Think of it this way, argues Conservative strategist Hamish Marshall:

“The environment/economy choice, I don’t think it’s a simple choice. I think a lot of it comes down to the inability to make a choice. The lack of certainty is in many ways, a bigger problem than the lack of a decision being for or against.”

In other words, it’s less about which road we take at the crossroads and much more about actually choosing one.

“If a project came forward and got a clear yes/no within six months or eight months or a year, there’ll be a lot more people willing to try different projects. Even if a project gets a yes or a qualified yes, but it took eight years to get to that point, I think that has a bigger impact on whether the next project gets built or the next project even gets discussed.”

Canada is facing a lot of challenges simultaneously, as you now understand, but our inability to make fast, decisive decisions might be the most pressing problem of all. And spoiler alert: it’s not a topic without controversy.

“We have all this discussion right now about environmental regulations and companies are going to get scared and not invest in Canada and all this. But realistically, environmental legislation is pretty weak in Canada.” – Dr. Victoria Lukasik | Biologist

“But it’s the amount of paperwork and legal process that occurs up front. That’s what I think Canada needs to take a look at, because that’s what in most of these big pipeline projects cost more than $500 billion and that just adds cost to the consumer at the end of the day.” – Hal Kvisle | Business Leader

“The absence of proper regulations will drive up costs.” – Dr. David Cooper | Biodiversity Expert

An Alberta that’s not respected within Canada is deeply troubling to me. I don’t think we should sit around and just watch that. I think we need to talk about how that can be changed.” – Donna Kennedy Glans | Former Alberta MLA

“I understand that some people are operating under a certain global perspective about sustained economic growth and continued resource extraction, but when we look at the nuts and bolts of it, those things are just no longer sustainable in our in our global reality, and so that no longer becomes a cultural issue. It becomes a very practical issue about what we can and cannot sustain.” – Nikki Sanchez | Media Maker & Environmental Educator

Who’s right? We asked Heather Scoffield, an economics expert who has investigated this subject as a journalist and again now with the Business Council of Canada.

“I would distinguish between regulation and red tape. Red tape is those annoying things that cost a whole bunch of money, or hold up decisions for years and years and years, and then make you just tear your hair out because things are going around and around in circles.

It’s like when you order something online and you get it home and it’s a little bit broken, and so you go online onto the chat bot to try to fix it. And then they don’t. They send you somewhere else. And then they send you somewhere else. And then you ask for the real person. Eventually you do, but then three weeks later, they tell you, ‘Okay, send it back’.

That kind of frustration that you get of just – can’t somebody please just say, ‘I have a solution for you’. That’s the kind of frustration that companies are living on a regular basis.”

That kind of frustration that you get of just – can’t somebody please just say, ‘I have a solution for you’. That’s the kind of frustration that companies are living on a regular basis.”

Randall Howard, of course, is a celebrated angel investor and tech entrepreneur. He has the pulse of Canadian start-up community and Randall tells us that red tape is frustrating, but adds:

“On a scale of the worst of the best – we’re not the worst, we’re not the best. There’s a role where we need the government to improve it, and hopefully this sense of crisis will redouble the government’s efforts to do it quickly and decisively. But at the same time, it’s not that bad. Our companies can succeed.”

In other words, don’t re-regulate everything? Heather Scoffield says:

“Deregulation is increasingly on the world scene. It’s embraced by some people. I don’t come at it that way. Good regulation in certain areas is very, very helpful in terms of bringing along the public, gaining trust, protecting health and safety and the environment. If a company’s initiative is surrounded by good regulation, then the public can have faith that this company is operating in conjunction with where society wants to go. It’s when regulation goes awry, which is a big problem.”

And, if we’re all being honest, regulations have gone awry.

“Regulatory burden is enormous. There’s something like 300,000 regulations out there.”

Hold on, what?

“Every time we have something going wrong, they go at each other’s throats, and the result is more rules. So we add layer upon layer upon layer of regulation, and then it turns out that after quite a few years of this, you end up not being able to do much of anything, because there are way too many rules to follow.”

As Heather argues,

“You want to be able to have a decision, have faith that it’s going to protect the public interest, but that’s actually going to allow a company to get things done. It requires a very big look at the regulatory burden. We have artificial intelligence for the intelligence for these kinds of things that can sort out regulations that are too old or misplaced or not meant for purpose.”

And while AI can help, technology can’t solve every decision-making delay.

Saugeen Ojibway Nation Ogimaa Chief Conrad Ritchie, as reported by The Pointer, said that governments need to remember:

“Indigenous rights are not red tape…The Crown is a treaty partner, not a dictator, and it’s time to act like one.”

This, of course, is in response to recent action by government – in this case in Ontario – to speed up decision-making. And no matter what piece of legislation we’re talking about, at any governmental level, many Indigenous leaders are deeply worried that our efforts to trim red tape might end up trimming constitutional rights instead.

As Mi’kmaq lawyer and Indigenous activist Pam Palmater told Breach Media, quote,

“You don’t get to circumvent the Constitution and prioritize private interests over constitutionally protected rights, because the Supreme Court of Canada has already said Aboriginal rights trump the interests of others…Corporations don’t have constitutional rights. We do.”

For this reason, Indigenous rights lawyer Kerrie Blaise argues.

“We’re seeing time and time again First Nations communities are coming before energy regulators. Various government decision makers are saying the duty to consult has not been fulfilled when there hasn’t been adequate public consultation. That has become a huge influence in whether or not the decision will go through or the final approval will be given for a project.”

And maybe we don’t value decision making processes to the degree that we should, but outcomes still matter.

“We risk talking too much and not doing enough. We have to think about how we have these conversations – fully and completely – but not necessarily dragging on and on and on.”

And when things do drag on and on, and businesses see too few outcomes, they often quit on the process and leave the country altogether. And that, according to Heather, is something that should concern us all.

And when things do drag on and on, and businesses see too few outcomes, they often quit on the process and leave the country altogether. And that, according to Heather, is something that should concern us all.

“There are a lot of companies in this country that are employing a whole bunch of people. If we don’t actually take good care to preserve that kind of thing, our quality of life is going to be hurt.”

Biodiversity expert Harvey Locke reminds us there is another urgent reality that also requires a quick decision.

“The urgency to accomplish something also needs to be paired with an urgency to protect something. And we have not shown urgency to protect in this country, either. We’ve had great policies and we can’t get off the dime. We’ve had a policy of protecting 30% of the country by 2030 and we’re still stuck at levels like 13% – where we were seven or eight years ago.”

The hard decisions we need to make? Indigenous community builder Shianne McKay argues they also need to factor in this reality:

“You can’t really address the environmental issues in the face of poverty. You have to address both.”

But accounting for different perspectives doesn’t always account for the urgency of environmental issues. Nor, as Dr. Brian Menounos explains, does it account for how indecision might impact all communities in this country.

“That will have implications. It will require perhaps some hard decisions in terms of relocation of infrastructure, perhaps additional costs due to rebuilding.”

But poverty? Jobs? The economic climate? The actual climate? The ecosystem services that support life on earth? They’re all trending in the wrong direction because we haven’t made a decision.

And maybe the ‘why’ is now apparent, but Conservative strategist Hamish Marshall tells us:

“Politicians that do not want to make difficult decisions have pushed more and more decision making to civil service. They’re looking to protect themselves as well, and to make a decision so uncontroversial by studying it in many ways to death.”

Hamish isn’t wrong according to the former mayor of Vancouver Sam Sullivan.

“Politicians will be very attuned to what might be cooperating if they go in one direction.”

Right! And as social innovator and generations expert Ilona Doughtery reminds us:

“Our leaders are reflections of us.”

That’s an important point because political fear is actually a reflection of our fear. Right, Hamish Marshall?

“We’ve been in an interesting place since we came out of the pandemic. We see a level of anxiety in Canada about our own future. Collectively, with some of the things that President Trump’s been saying, but also individually, when it comes to issues around affordability and the feeling that the future is not a generally positive place.”

You see, Hamish is a numbers guy. He’s not only a strategist, but also a pollster and demographics expert.

“I find that numbers reveal some truth about the world. When you’re telling a story, we all sometimes edit the story to make it sound a little bit better, or we try to make patterns fit onto narratives. And I find that numbers sort of force an honesty on you. If the numbers don’t quite line up, it’s harder to make the story work. The problem with numbers is that there’s a lot of them. You can find numbers on anything. In baseball in particular, you can have 10,000 different statistics on an individual game. Many of them are interesting, but kind of irrelevant, and I think that politicians have spent a little less time taking the time to understand the anxieties of Canadians. This is a bit about understanding that numbers matter, but that actually it’s how people react to the number that’s in their lives that really matter.”

Cultural anthropologist Sierra Dakin Kuiper also agrees that we “start contemplating and think critically about how people react to the problems in their lives.”

Sierra adds, “It’s really important that we consider who hasn’t really had a voice at the table in terms of making these decisions.”

When we hear that? We often assume we know who doesn’t have a seat at the table; who doesn’t wield power in our society. And that’s often a correct assumption. But get this: Hamish Marshall argues that many more Canadians also feel as if they don’t have a seat at the table; that they too feel unheard and disrespected.

“When Pierre Poilievre said that Canada is broken, there was a chunk of society that went, ‘This is outrageous. How dare he say such an awful thing?’ And actually, Canada is doing great, but a lot of Canadians went and looked at that and said, ‘Yeah, this isn’t working for me anymore’. And they are angry about it.”

What isn’t working?

“A deal that’s existed or was seen to exist anyway, which was – work hard, go to school, learn some skills, you get married, you buy a house, you have some kids, you’re going to have a job that’s going to allow you to do all of those things. You’re going to have a career, and you’re just going to be going through ups and downs, but broadly speaking, you’re going to be able to have a good life. And this deal isn’t working anymore. People are working their tails off two jobs, sometimes three, and they’re barely getting ahead, and they certainly can’t afford a house in a major city. And that’s the people who have good jobs.

That anxiety has gotten into our national psyche in a variety of ways. For some people, it creates anxiety. For some people, it creates anger. For others, it creates an attitude of giving up, but that feeling that you do everything right, you might not be okay, is at the core of it.”

Why is the deal broken?

Why is the deal broken?

Let’s start here:

Decision making is hard. Always has been.

It’s why kicking the can down the road or making stop-gap decisions with minimum political fall-out are easy choices.

Consequences? They’re for tomorrow! Elections! They’re today!

But because leaders are a reflection of us, for decades we’ve rewarded and even incentivised this behaviour. After all, we prefer instant gratification too!

Each punted decision made making the next decision even harder. But stubbornly stuck with the instant reward.

As time passed, changes in our media landscape gave our society more and more agency. That’s a good thing, obviously, but with more people coming forward with opinions that must be considered, the more complicated decision-making processes became. Ones that were already becoming more complicated because of our previous can kicking endeavours.

Delays, no matter how just, feed apathy. And to avoid apathy, decision makers tried more half measure and more can kicking just to keep the masses happy. And that?

“When you can’t find a job, or when you’re stuck living at home and you don’t want to be living at home, or any myriad of things, you have to make choices purely based on the economics of it. That’s really frustrating.”

Social innovator Ilona Doughtery is right. And that frustration, ironically, only further amplifies indecision and the vicious cycle continues. And this cycle? As biodiversity expert Harvey Locke argues:

“The frustration about not getting stuff done is everywhere. It’s not Canadian. There’s a global sense that the system isn’t working so well

What’s more Harvey adds:

“It’s because of this sense of everything being stalled and the system’s not working. That gives you this deep frustration that gave rise to the phenomenon that we see in the United States of Donald Trump and to ‘Make America Great Again’. I view the president not as the person responsible. It’s a movement that has arisen in response to conditions that needs to be replaced with something better.”

In the case of America, it’s not just that a swath of the population that feels like things aren’t going well, as pollster Hamish Marshall argues, there are tangible indictors that demonstrate things aren’t going well.

“The statistics that really brought it home to me in the United States, people who were white without college degrees had seen their life expectancy decline in the richest country in the world. That was a canary in the coal mine that the American Dream has stopped working for a large chunk of the population

Hamish adds, “We have to really be aware of that.”

Why? For two reasons.

For one, we need to have at least some empathy for those who elected US President Donald Trump if we’re ever to overcome the threat he poses to our nation. After all, Trump’s hold on power, at least for the moment, thrives on the anger and frustration of his voter base.

“There needs to be empathy. Absolutely.”

The other reason we need to be aware of why people are angry and frustrated in America is because it’s instructive for us.

You see, while all movements – Trump’s included – need a catalyzing moment, they also require seeding. Decisions – or non-decisions and half measures, no matter how well-intended – can, with time, grow and fester.

And while we haven’t reached the tipping point yet…

And while we haven’t reached the tipping point yet…

“I don’t think we’re there yet, looking at the polling, but I’m not going to say we won’t be in few years down the road.”

Exactly. So, if Canada is to start making decisions, getting our nation unstuck in the process, we have to be very sure they’re good decisions.

After all, as the saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

“If the system isn’t working anymore, why, for certain people – what isn’t working? And put some effort into that and realize that many of the solutions that have been put forward are not actually working.”

Here’s what Hamish means.

The Globe and Mail newspaper dug into why certain regions of America flipped from backing former US President Obama, a Democrat, in 2008 and 2012, to backing US President Trump, a Republican, in 2016 and 2024.

And the answer, it turns out, can be found in the history of Grays Harbor, Washington State.

Sixty years ago, human behavior started impacting the spotted owl in the western United States. Populations started collapsing and scientists started calling for action to curb loses that they worried would eventually impact the ecosystem services people rely on. But not wanting to regulate development or cause job losses, the relatively small action required wasn’t taken.

And the problem continued.

Then, about forty years ago, the issue became so acute urgent action was required. The near total ban on logging in areas around Gray Harbor was so severe that locals still blame the move for destroying their local economy and creating the conditions that have allowed the Fentanyl crisis to take hold.

The policy was well intended and science-based, but cultural anthropologist Sierra Dakin Kuiper says that decisions like this one “there isn’t always the feeling that the community is being heard.”

For this reason, Sierra believes:

“By really learning more about all the different perspectives and all of the historical context at play, people can start to see where good intentions have gone awry in the past and really learn from those mistakes.”

In the case of Grays Harbor, the mistake was failing to secure local buy-in for a scientifically rigorous and important goal.

When this happens, Sierra argues, it feels “more like there’s an agenda being imposed on them.”

See? The seeds of anger and dissent. Seeds that grow when jobs are lost alongside hope that the American dream is still attainable.

Of course, the value of saving the spotted owl – saving biodiversity – will rarely stack up against the here-and-now pocketbook and crime issues that drive electoral politics. But when the efforts to protect the spotted owl – biodiversity – have also failed? Well, seeds of frustration are planted within another swath of society.

Dr. Victoria Lukasik is a biologist and she says that when governments don’t listen to the fullness of science and make the hard, right decisions before the problem gets out of-hand?

“There was a lot of cynicism, especially for people who’d been at the job a long time, they don’t get to do what should be done because of the politics around it.”

There is an argument to be made that, in both Trump victories, this cynicism and frustration led some voters to stay at home or to cast ballots for third party candidates. At the very least, a pocket of disenfranchised citizens is increasingly rallying behind harder left-wing candidates, further polarizing the broader electorate.

After all, this too is a vicious cycle. Each time one side of a debate advocates for, or legislates a policy, that is seen to be extreme by the other side, the opposition will dig in their heals and react in kind, pushing the two sides further apart and making good decisions that much more elusive.

As former Conservative leader Erin O’Toole points out, “well, we’re not America.”

Our own indecision and half measures have allowed the problems we face to fester. The seeds of Gray’s Harbor, like resentment, have been planted all across our nation, and if we’re not careful, even well intended decisions made to help us navigate this moment, could end up pushing our divisions, our democracy, over the edge.

After all, as pollster Shachi Kurl explains, “because this really comes down to in economic terms, a perception of winners and losers.”

Conservationist Ken Wu goes further, “there are going to be winners and losers.”

Ken, the founder of Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, is saying the quiet part out loud – something most know, but many are afraid to admit. But it’s refreshingly honest and he’s not wrong: No matter the solution, there will almost always be some losers.

Ken, the founder of Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, is saying the quiet part out loud – something most know, but many are afraid to admit. But it’s refreshingly honest and he’s not wrong: No matter the solution, there will almost always be some losers.

And though Ken adds “we don’t have to have as many losers as people often think”, the reality is the idea of having any losers in a major policy decision with social, environmental and economic reverberations doesn’t sit well with a lot of us.

No one wants to be a loser; everyone is afraid they’ll be the loser. People worry it’s their closely held ideals and their deeply ingrained values that will be sacrificed at the altar of tough decisions.

So, yes, this is absolutely true:

“I have been a very active investor in early-stage companies. One characteristic of all of those companies is they’re very different than many of the companies and jobs that came before them. Whereas Canada was heavily resource based. These new businesses, which I would call knowledge-based business, is helping to decarbonize our economy.”

And while investing in the knowledge economy, sounds like a great plan. Rural advocate Joel McKay wants you to understand: “the policy, frameworks and structures we use to order our country are not conducive to rural development.”

Joel is the CEO of Northern Development. He advocates for rural communities and rural economies and as he reminds us, “80% of the population of Canada lives within two hours of the US border. And the vast majority of those individuals live in our major cities, which are quickly becoming city-states. Canada and its provinces need to have a serious look at how we recognize and support rural development.”

For Joel, this means recognizing a simple truth.

“Rural communities, especially those in the North, have few realistic options for private-sector employment that are outside of natural resource industries.”

That means for the 909 communities in Canada that rely heavily on the resource industry, some communities simply won’t be able to survive if the broader national economy shifts away from resource development.

Joel says, quote, “We need an environment that supports resource extraction, attracts investment and leverages the benefits generated from that to reinvest in rural areas so that they have just as much opportunity as our urban areas.”

If this doesn’t happen? Some fear they will be the ones who will lose work – some fear it will be their community that doesn’t survive.

That fear is both founded and unfounded.

Huh?

Well, maybe a little history lesson is in order.

Red Pass and Lucerne? These were once bustling communities. Of course, both of these locations are now part of present-day Mount Robson Provincial Park and have been for a long time. And it’s been an even longer period of time since these places were more than ghost towns.

Why? Change, of course.

Red Pass and Lucerne were the by-products of a by-gone era – one where travel and trade was limited to the railroad. In those days, train maintenance requirements often dictated where towns were established, with these needs bringing settlers to the region in search of work.

And though the railway still runs past the ghost towns of Lucerne and Red Pass, the maintenance needs have changed, and so too have employment requirements.

The consequence? Towns faded away.

Indeed, in many parts of the country, towns came and went with the railway, but the ones that survived in rural Canada often evolved from rail-based tourism and focused on what nature provided: Natural resources.

And as local community builder Bruce Wilkinson explains, Valemount, on the west border of Mount Robson, was no different.

And as local community builder Bruce Wilkinson explains, Valemount, on the west border of Mount Robson, was no different.

“It wasn’t tourism-based when we moved here; it was it was the forest industry.”

But Bruce wanted to take advantage of the nearby provincial park.

“BC provincial parks offered an opportunity to run a business in the park, which hadn’t happened before.”

It was a turning point, in some ways, for the community of Valemount which now relies increasingly on the tourism sector for jobs.

That should make Mount Robson beloved in Valemount, but according to local historian Art Carson, many living in the Robson Valley “have seen that as basically outsiders putting nature ahead of human beings.”

In this case, the outsiders who created the park was the railway company that, ironically, also gave birth to Valemount and, for years, brought its natural resources to market.

No matter.

For decades, forestry jobs were obvious and seemingly in endless supply and, as Bruce Wilkinson tells us, the park’s economic value was less obvious.

“Historically, so few people have been working in the parks that they can’t see the value.”

Here’s the rub: forestry is less obvious today.

As professional forester Art Carson adds, the forest industry “won’t be quite the massive scale that it was.”

Art’s right. Forestry has changed in the wake of the pine beetle infestation that killed millions of trees and forever changed the region’s number one employer. Still, citizens can’t stop the pine beetle – not directly, not overnight.

But parks are a human construct. In theory, what was created with the stroke of a pen can also be undone by the stroke of a pen. And Bruce Wilkinson says that’s exactly what some want to see – no matter how many jobs the park has created.

“They still…I don’t know if everyone sees the value of the park.”

Keep in mind, Mount Robson has existed for over 100 years, yet the conversation – the resentment – continues, at least within a portion of the population.

In this country, as with most, identity is tied to land, to place. To forge a shared national identity to help us navigate this moment, it’s going to be hard to ask some to give up their ties to specific land and place.

In this country, as with most, identity is tied to land, to place. To forge a shared national identity to help us navigate this moment, it’s going to be hard to ask some to give up their ties to specific land and place.

And then there’s this: the communities that are especially determined to survive are determined to do so because they want to protect their local culture. And that local culture? It can be at odds with that vaunted national compromise.

It’s why communities and organizations are deeply opposed to the creation of new parks in the most biodiversity rich and sensitive areas of the country – the Bighorn in Alberta, the Okanagan in BC. Why? New parks would regulate or ban hunting and activities like ATV use.

As Neil Fletcher of the pro-hunting BC Wildlife Federation explains,

“When you take people’s ability to go hunt on the landscape out of the picture, it actually removes them from the landscape – from caring about the landscape – and takes away a connection that they have to the landscape.”

And that’s why, Neil says, those protective of rural communities worry about the impact of parks and tourism.

“Recreational activity or roads can have just as much of an impact as can hunting, if not more.”

And, you might say, hold on: BC Wildlife Federation is against the type of tourism that goes hand-in-hand with parks, but also wants more types of recreation allowed inside and outside of parks? Yes, and it makes sense, according to cultural anthropologist Sierra Dakin Kuiper.

“So, roads, campgrounds, that sort of thing…would actually take away what (rural communities) so loved and really valued about that landscape.”

Indigenous land-use advocate Chloe Dragon-Smith hears the point. In fact, she says:

“Being able to govern and manage our own lands, as we have for millennia, often looks very, very different than the conventional conservation that we think about when we think about parks and protected areas. It often means people being much more engaged in lands. Definitely harvesting, hunting.”

Hunting in provincial protected areas is common, but it’s banned in some parks like Mount Robson and in national parks as well.

Until recently.

You see, many places, like Robson and Jasper, have started allowing traditional Indigenous hunts.

You see, many places, like Robson and Jasper, have started allowing traditional Indigenous hunts.

“When the Simpcw came in and they conducted a traditional hunt, the outrage that I heard – and the vitriol of that outrage – was borderline racism, from people that I know even. And I don’t think that they’re racist. They’re just ill informed.”

Joe Urie is the founder of the Jasper Tour Company and is a champion of Indigenous rights.

“The hunt was conducted to reacquaint the Simpcw and their youth with the land. The amount of the animals that were taken was minimal.”

But when rules change for one culture, rightly or wrongly, other cultures want to be included too.

Though Dominic Dugré, the president of the Canadian Federation of Outfitter Associations, certainly supports Indigenous hunting rights, he wants those rights extended to all citizens.

“There needs to be a way for national parks to handle their wildlife. For example, the elk populations in Jasper have exploded beyond what the region can accommodate, resulting in habitat destruction and dangerous encounters for humans.”

That’s something photographer and wildlife advocate John Marriott has a problem with.

“I have always felt that our wildlife doesn’t have much of a voice speaking out on their behalf. So much of our so-called ‘wildlife management’ is run on a consumptive basis (by hunters and trappers). But this ignores completely the intrinsic value that nature has and that wild animals and wilderness offer to the majority of us.”

John’s beef isn’t with the Simpcw’s traditional hunts in Jasper and Mount Robson, but with those who want to see the hunt extended to all peoples in all parks.

But many worry that by granting certain rights to one culture, a door will be opened to extending those same rights to other cultures – changing everything in the process.

For others, the worry is that by elevating the rights of one culture, there will be even less space for their cultural traditions.

For others, the worry is that by elevating the rights of one culture, there will be even less space for their cultural traditions.

It’s why pollster Shachi Kurl reminds us that we need to ask, “well, who’s equality? Whose social justice are we talking about? The intersections here get pretty complex pretty quickly.”

They do but just because our choices are hard and at times contradictory doesn’t mean that we should kick the can down the road.

As you now understand, we need to make decisions quickly, decisively, now more than ever, but in the doing, we need to be honest about the impact of our decisions now and in the future. And we need to make sure that the decisions we make account for everyone who calls this country home.

In a moment of crisis will we think critically enough be brave enough to ask all of the questions that must be asked and decide on a path forward. The knee jerk reaction is of course, but that’s only if we generalize, only if we refuse to be honest, that the sum of the parts is different than the parts that make the whole. And we can’t generalize just to make our life or a solution easier, a solution should be mostly possible, but will it be always possible? And what happens if it’s not possible or not possible in every region. What culture can we overlook? What community is it appropriate to sacrifice? What animal or ecosystem can we afford to lose?

After all, in trying to make better decisions, even justifiable decisions, for one community or one group of peoples, the decision might impact or restrict the values of others.

In a moment of crisis, will we think critically enough – be brave enough – to ask all of the questions that must be asked and decide on a path forward?

The knee-jerk reaction is: Of course. But that’s only if we generalize – only if we refuse to be honest that the sum of the parts is different than the parts that make the whole. And we can’t generalize just to make life – or a solution – easier.

A solution should be mostly possible. But will it always be possible? And what happens if it’s not possible? Or not possible in every region? What culture can we overlook? What community is it appropriate to sacrifice? What animal or ecosystem can we afford to lose?

“It’s so important that we bring controversial ideas into public discussion.”

The former mayor of Vancouver, Sam Sullivan, is right. But how do we do this?

“I think part of the answer is to have a discourse.” – Pete Smith | Rural Advocate

This will involve having difficult conversations and making hard decisions.

“And I think so much of the debate on so many issues in this country has really been boiled down to it’s this or it’s that, and it can’t ever be both. We have lost the ability to question respectfully, without being accused of being a terrible person or not being patriotic or this or that, we have to get away from that as individuals.” – Shachi Kurl | Pollster

“I come back to the personal responsibility that we have to make an effort to listen to people whose views are different and to enter those discussions with a willingness to learn.” – Janet Austin | Former Lieutenant Governor of BC

“I’m just convinced that if there’s a bit more of a willingness to have those kinds of discussions, there is common ground.” – Pete Smith | Rural Advocate and Artist

“In a democracy, a society can only move forward and accomplish any sort of agenda if there is some consensus.” – Peter Biro | Founder of Section1.ca

“The biggest problems tend to be the ones that really are these wicked problems that require collaboration amongst every group. They never are completely solved, and it really is always about making progress.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Cabinet Minister

“And consensus is not the same thing as compliance. Consensus is that incredible thing that is produced by the marketplace of ideas and also by a democratic political system in which people have to agree, or at least be seen to agree or tolerate a particular direction.” – Peter Biro | Founder of Section1.ca

“In other words, it’s not always about getting every single thing that you want.” – Pete Smith | Rural Advocate

“We got to get back to – let’s respect each other. Let’s respect difference, but also, let’s go somewhere specific.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“We need to give some more courage, back to our politicians and realize that maybe they’re only going to get it right nine times out of 10.” – Hamish Marshall | Conservative Strategist

“Sometimes there’s a common-sense compromise, and sometimes you got to make a hard choice.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“Often, we don’t recognize that what we’re asking for cannot be achieved in the short term.” – Janet Austin | Former Lieutenant Governor of BC

“One does need a group of citizens to be well informed. There’s no question about that.” – Hamish Marshall | Conservative Strategist

“There’s nothing about liberal democracy that comes naturally. It requires a lot of learning and a lot of moral courage, because it puts the citizen not in the driver’s seat, but in one of the many seats that contribute to the driving of the agenda and of the governance of the country.” – Peter Biro | Founder of Section1.ca

“One of the most powerful things that young people can do is talk about ideas. Young people don’t realize how powerful their voices are. They have way more power than they think they do. And part of participating well in a democracy is to shape, not only to be shaped. You can shape, and that’s your power. And if you say, ‘this is the world I want, and I’m prepared to work for it, and I’m prepared to talk about’. It has enormous power.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“So finding something – that one thing that you really care about – and then working towards it.” – Heather Scoffield | Journalist

“Make sure, before you lead, you have followed and you have walked a mile in their shoes. You can’t ask people to do things that you’re not prepared to do yourself.” – Pete Smith | Rural Advocate

“And we can do it. That’s the funny thing. We can always do it. It’s just whether we choose to or not.” – Heather Scoffield | Journalist

“We can make those differences and create the things in the world that we know need to be there.” – Dev Aujla | Founder of DreamNow

“We’ve got to believe in something to get it done, and then we got to do the hard work to do it.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“We can save us.” – Dev Aujla | Founder of DreamNow

“The world needs us to succeed.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

And maybe in trying to make quick, hard decisions, we also need to realize that seeing success in our outcomes will and must take time.

And maybe in trying to make quick, hard decisions, we also need to realize that seeing success in our outcomes will and must take time.

“I think we need to advance change as rapidly as we possibly can and as rapidly and as proactively as our society can manage it. But we need to recognize that change does take time, and cultural change is part of that.” – Janet Austin | Former Lieutenant Governor of BC

“If we take a hyper aggressive and quite frankly, unrealistic approach, we will sow more division in the country at a time when we need more unity.” – Erin O’Toole | Former Leader of the Conservative Party

“If we want to move forward on any major social, cultural, environmental change, we need to bring people along. We need to engage people and unless we’re actually able to capture the imagination and the understanding of our population more broadly, we won’t achieve the success that we need to achieve.” – Janet Austin | Former Lieutenant Governor of BC

“I think history teaches that really is a case of social evolution, and with time, you get there.” – Monte Solberg | Former Conservative Cabinet Minister

And maybe that reality must also be balanced with this reality: middle of the road compromises and incremental strategies are partly to blame for the situation we’re in.

“We get apathetic when we can’t see any change when we try and we pour our hearts out and nothing is different.” – Barbara Cartwright | Humane Canada

“The idea of doing only small things in the belief that an accumulation of small things is somehow randomly going to result in the outcome you want maybe over four and a half billion years, if the evolutionary theorists are right, but not over the next 40 years.” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

“There’s nothing actually wrong with us. It’s just that we’re not as hard hitting as some other some other countries are, in terms of taking what we have and applying it really hard. To take some risks, you’ve got to put your money on the table there and say, ‘Okay, we’re going to do this thing’. And right now, we’re not actually seeing that. We’re just seeing a lot of ideas, and a lot of people throwing up barriers in front of those ideas.” – Dr. Kate Moran | Scientist

“Energy policy is made at a high level. It’s not made at the level of your choice to ride a bicycle. Your choice to ride a bicycle, could be a positive thing, but it doesn’t change energy policy. Energy policy changes energy policy. They’re made in service of something. What is it we want to serve? And what are the policies we want? What are the specific actions we need to take to get there? What are the outcomes we get?” – Harvey Locke | Biodiversity Expert

Act urgently and think big, while also being patient and progressing at the pace society can accommodate.

“That may seem like a bit of a paradox, like a bit of an internal contradiction.”

Lawyer Peter Biro is bang on, right artist Pete Smith?

“I think the opportunity is for us to evolve. Actually, I think we’re at a point where it isn’t about trying to get back to what we had. It’s actually to look ahead to where we’re going. That notion of, ‘I can hardly wait to get back to what we had’, that’s not available. It’s not just Trump and tariffs. It’s also the shape of the world we live in and what we have done over the last 150 years, which is amazing in many cases, but is also really detrimental to our quality of life.”

In other words, we can reject the binary choice that appears to be on offer.

“In that way, that’s when new ideas can come in, and other things are happening. It’s when you get away from the ‘that’s not the way we do things’. When we start to loosen up, and go ahead and think, ‘have I thought about that’, or, ‘what if we did this’?” – Pete Smith | Rural Advocate

This is where art can help.

“Creativity gets you unstuck from your thinking. There’s an opportunity here to go, ‘okay, the colour purple, I never thought about like that’. If you can get unstuck in the way to think that somehow, that’s the only way to think creativity, that door that opens and gets people into an environment that is less judgmental, freer, and also, you feel your breath, your shoulders drop, and then you bring the best to yourself – the shiny part of yourself – to the conversation.”

Dr. Aleem Bharwani agrees.

Dr. Aleem Bharwani agrees.

“You just need to turn that Kaleidoscope, where you’re looking at that those same pieces, that same wall, and some components, turned a slight way, and now suddenly you can drive that line of inquiry in a very different direction.”

Turning the kaleidoscope allows us to see challenges – like the ones we’re facing – from new perspectives.

How?

Well, for starters, what if an innovative idea can help us shift from environment versus the economy to environment and the economy. It sounds naive, but here this idea out.

“How do we start getting the financial system to respond to the need to protect and attack nature and restore degraded nature?”

Harvey Locke is a big ideas guy. He’s advised governments globally on how we can balance the needs of people and nature.

“The real problem is we don’t know how to finance and attack nature with private money. The only way we’ve been doing it is with government money, and governments are saying they’re too broke to do the job. We need private sector participation. I’m working on how does that happen?”

Good question!

“Can you imagine environmental risks on the on the risk side, and can you imagine insurance products that might offset that environmental risk, that the premiums get paid by people who would suffer the risk, and the money that’s paid to the insurance is deployed to prevent the risk. That’s an example.”

Here’s the issue, as Harvey sees it:

“Right now the financial system is biased towards nature is free, so it’s not worth anything. It’s just doing its job keeping the world running. That is the problem we have to fix, and we have a fundamental market failure. We don’t consider nature worth anything until it’s basically dead and turned into a commodity. That has to change.”

Harvey says, think about it this way:

“Gold is valuable and art is valuable, and things like Bitcoin are valuable, because why think about it for a minute? They’re valuable because they’re valuable. People perceive value. perceive they will increase in value. Therefore they buy them. Well, you can create investment options, whether through coins or through company shares that secure intact nature on the premise that it’s valuable, therefore you should invest in it. It’s no different than gold. It’s no different than art. It’s no different than Bitcoin. It’s far more valuable than all those things, because those things have value, because we perceive they have value. Nature has actual value, which is not perceived. It’s fundamentally real.”

Former federal Conservative cabinet minister Monte Solberg agrees.

“I would argue the policy that underlies almost every other policy, our land and water and air, is what produces everything that we have.”

Harvey Locke adds:

“Nature is the context for all business and all finance. You can’t have successful economic activity if we continue to degrade nature. Large financial outfits are starting to see this. So it’s really an interesting moment where this idea called ‘Nature Risk’ is arising.”

And Indigenous rights leader Dr. Leroy Little bear concurs.

“As humans, we have a very narrow gap of ideal conditions to make for us to exist, if you start plucking away at those ideal conditions, well, things are going to change.”

And here’s the thing about change:

And here’s the thing about change:

“The polarization is occurring because of this kind of stress. The change is more profound. We’re in a time of more change than any time in human history.”

Futurist Jim Bottomley is bang on. So maybe less upheaval will help us. After all, as pollster Shachi Kurl says, “it’s all about don’t change much. Make changes that are meaningful but manageable.”

And while Harvey Locke’s Nature Positive idea will bring about some change, this proposal at least attempts to take our compounding problems and find a decisive answer that can simultaneously address our economic and environmental problems while also working with, rather than against, our existing culture.

“How do we begin thinking about things as investments rather than costs? Nature is a classic thing that could go on to what you call the national accounts or the balance sheet as an asset instead of a resource that’s unexploited. Then the financial perspective of what these places are would be much healthier, which would help with their cost of borrowing.”

Harvey offers an example.

“What is a country rich in? Well, if you look at the GDP of Singapore, which has tremendous financial markets and a very industrious people, it doesn’t have enough water, and they know it, and they worry about that. We as Canadians have lots of water, but instead of valuing the source of the water, we say, ‘Oh, well, where the water comes from? On the eastern slope of Alberta, that waters all the prairie provinces. There’s coal in there, and then we got to get that money out of there’. Well, just a minute there’s water. That waters for several million people. That is the foundation of the entire economy of the prairie provinces, and you’re going to go pollute it with a coal mine. That’s nuts! But we don’t value the water.”

Is this just some wild idea out of left field?

“There’s this thing called The System of Environmental Accounts of the United Nations that has been agreed to by 90 countries, and Statistics Canada uses it off in a dark corner right now. So this idea of environmental accounting is to say, ‘well, we should look at natural capital of living and non-living parts of the world – biotic and abiotic – and then we should recognize what the flows are that benefit people from that. And we should put that on our balance sheets, as well as the money stuff’.”

Amanda Gierling with the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions believes that the environment should be on our federal balance sheet.

“I absolutely think it should.”

The United Nations’ David Cooper agrees as well.

“We certainly need to look at how we regulate and incentivize the management of areas that contain nature to realize the value of those elements, those ecosystem services, if you like, those contributions that people get from nature that are not currently marketed. We may need incentives.”

As Harvey Locke adds:

“I believe we’re in a really important crossroads. If we double down on what we’ve already been doing in our relationship with nature, it’s just going to get worse, but if we take this opportunity to embrace something different, it’s going to get better. We’ll have something to believe in. And what fun is that.”

Whether you agree with this idea or not, the bigger point is this:

We need a turn of the kaleidoscope to re-imagine what’s possible in a moment like this.

We need to reimagine our problems and the possible solutions. We need to find ways to account for those we disagree with in what we create. We need find our common identity – our common humanity – so that we can work fast and decisively to address multiple issues at once. Mostly though, we need to be able to work together.

This isn’t to say we can avoid all division and disagreement, of course, but maybe we can avoid some, especially along our traditional fault lines.

And if we could avoid sending our traditional, national solitudes to their traditional corners for a pitted culture war – Indigenous values versus non-Indigenous values, pro-environment versus pro-economy, urban versus rural, east versus west – what might that mean?

It could be the spark needed for old adversaries to build new alliances, reshaping our debates and bridging our divides in the process.

After all, we can’t live in a world of zero-sum wins that cost more than dollars or species, but also the very health of our democracy.

We must do better.

In the words of our former prime minister, Kim Campbell:

“Create, as much as possible, bridges with people who may not think alike. Try and find ways of building around dogmatism and political polarization by finding the common ground. And it’s hard.”

After all, as economics expert Heather Scoffield points out:

“I don’t have the magic solution. I don’t think that should stop us from trying.”

Exactly. Because in trying? In being courageous?

“You always have to achieve things, to demonstrate the art of the possible, but you also have to have it possible.”

Harvey Locke is right. And it is up to all of us to demonstrate the art of the possible, now more than ever.

“People know something is wrong. 20 years ago, if you were pushing an idea, you were pushing it into a status quo that most people thought was good enough.

The metaphor I saw once is: Are you trying to add a box car to a southbound train? Everybody wants the train to be south bound. So will you be allowed to add a box car to it or not? And now people are prepared to entertain that there should be a northbound train, not a box car going south, but the train should turn around and go north. There’s more openness to that now than there’s ever been. I’m really excited about that, but it’s also a responsibility.

What are we going to do? Where is north? How do we plan to go north instead of south, which is actually going off a cliff? So let’s turn around and go north.

What does that mean? Well, it means we put on the brakes, and then we lay some track that does a U-turn, and then we start heading north.

Let’s get at it. Let’s lay track together, and let’s start moving north together. But the idea that, ‘well, I can see we’re going south, and what a bummer, man. And look, it’s his fault I’m going south. And tear him down, because he was in the train when it was heading south. So he’s part of the problem. She’s no good because she’s in the second box car’. It doesn’t get you anywhere except off the cliff.

So how about sure everybody is part of where we’re headed, and we got here together. Now we need to get somewhere else together. So let’s GO!”

What do you think?

Terms & Concepts

Referenced Resources

* Quotes have been edited for brevity and clarity.