Estimated Read Time: 18 minutes

Can we save every species?

This class isn’t just theory; it’s not abstract.

This class is the foundation for understanding real issues in the real world – issues that affect you and me, today and tomorrow.

How so?

Well, for starters, it’s the first step towards understanding what it will take to truly balance the needs of people and nature.

Does that matter?

Well, this challenge is as pressing as it is interwoven with other issues we face – problems like economic insecurity, social justice and democratic health.

By finding a better balance between people and nature, we can create a ripple effect of understanding and possibility to tackle other, at times, more divisive issues in our society.

Maybe you think: This isn’t a hard challenge – the solutions are obvious.

Yet nothing is as easy as we assume it should be, in part because even when we think problems are black and white – good versus evil – they rarely are. Almost every issue is maddeningly complex, made all the more difficult when emotions like uncertainty, anger, hopelessness and fear are added to the mix.

And about now, you might think, well, none of this is actually my problem. And it probably shouldn’t be. But it is.

You see, not only are decisions being made today that will directly affect your future, right now, you are also entering your years of peak creativity.

As Ilona Dougherty argues, “young people from 15 to 25 are at the height of their lifetime ability to be creative, to be innovative. All these incredible abilities peak during that time of life, and they have the full intellectual capacity of adults. We underestimate young people all the time and we need to stop doing it.”

Ilona knows better than most. She co-founded Apathy is Boring as a student and is the co-creator of the Youth & Innovation Project at the University of Waterloo. Her ground-breaking research has proven that your ideas, with help and refinement, are the very ideas that can help us create that better balance – that better tomorrow.

Ilona knows better than most. She co-founded Apathy is Boring as a student and is the co-creator of the Youth & Innovation Project at the University of Waterloo. Her ground-breaking research has proven that your ideas, with help and refinement, are the very ideas that can help us create that better balance – that better tomorrow.

“The research is very clear,” Ilona says. “For young people to grow up to be healthy, engaged adults, it’s all about having a sense of purpose and having an opportunity to make impact.”

In other words, you might feel that you’re just one student, without the power or influence to determine how late you can stay out on the weekend, let alone solve the world’s problems, but the reality is quite different.

As Ilona explains, “The only way to be a change maker is to be a change maker while you’re young.”

That’s right: You’re powerful because of your age. You can solve any problem we face because of your creativity.

“Young people have unique abilities while they’re young that society needs.”

Exactly, Ilona. And we all need your creativity. Right, Dr. Aleem Bharwani?

“Our most influential and impactful ideas will come from young people today who are growing up in this world.”

Adults – leaders – are so immersed in the problems we face they often can’t see the forest for the trees.

We need you to take a new look at old, if worsening, problems to see if there is something everyone else has missed. We need you to understand how hard truths collide and find ways to do better by different peoples and different communities – do better for more people and for nature.

Because we can all agree that we need to do better.

Discuss

Good points, but let’s get really specific.

Scientists have analyzed Earth’s record-keeping system – fossils – to understand how often natural selection creates natural die-out – what’s known as the Background Extinction Rate. And though no one is certain – fossil records aren’t quite the Wayback Machine – most believe one species goes extinct per Million Species Years.

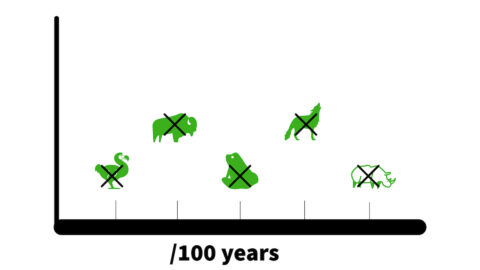

Our current extinction rate, depending on what mathematical equation you believe and use, is ten-to-10,000 times higher than the planet’s Extinction Background Rate – the ‘natural’ natural selection, if you will.

Which is a big spread, but consider this:

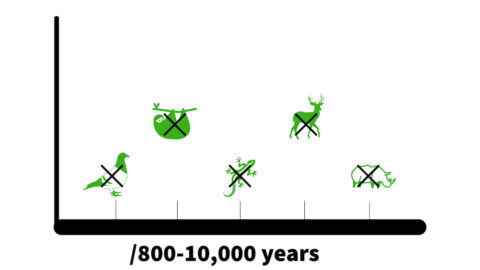

Of the species that have been known to exist and disappeared during the last century, their loss should have taken 800-to-10,000 years to occur. Not the 100 years it actually took.

And that’s according to a study that used a “conservative background rate of two extinctions per million species-years.”

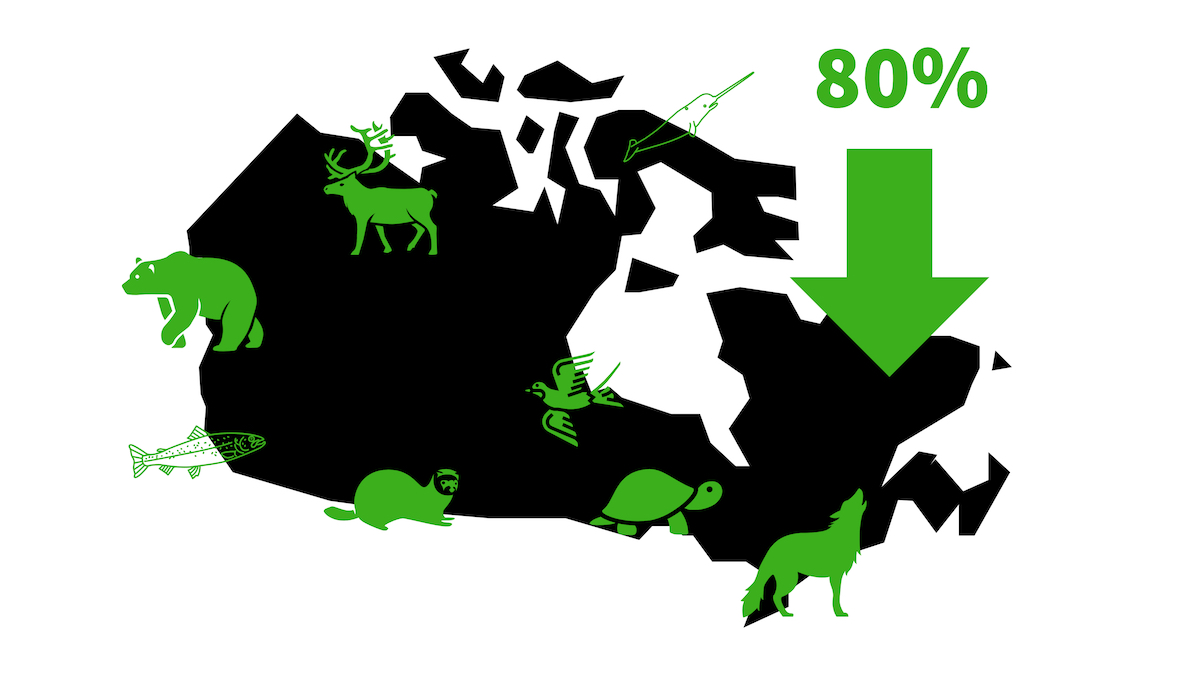

Globally, nearly 70% of every monitored species is either decreasing in population or range, or both.

In Canada, a recent, comprehensive report that combines data from every level of government suggests that of the 50,500+ species we monitor, 1 in 5 are facing at least some risk of being lost and for 2,000 of those species, they’re at high risk of disappearing from Canada’s landscape.

Those are big, worrying numbers – and the problem is increasing. Fast.

How fast?

Well, according to the World Wildlife Fund, the largest environmental organization in the country, their research suggests that the average populations of threatened species in Canada have declined by almost 60% – with some data suggesting that for half of those species in decline, they’ve lost more than 80% of their population numbers in just 50 years. It’s a major reason why more than 500 species are legally listed as being at risk of extinction by the federal government.

For all these reasons, some have concluded that we’re entering a period of mass extinction – a cycle where roughly three quarters of all species disappear in a span of a few million years. There have been five in history – of course, the most famous being the one that whacked the dinosaurs.

If we’re entering a sixth mass extinction, unlike past extinction events, this one is human-caused, scientists tell us. But that is, of course, a debate and, frankly, not a particularly helpful one.

Why?

Because the why distracts from the real issue: Un-natural natural selection at a rate well above the Background Extinction Rate means only one thing: Biodiversity loss.

“The bad news is that in most parts of the world it is declining and it’s declining at all levels.”

David Cooper was the Deputy Executive Secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity – a United Nations body that works to coordinate global efforts to protect biodiversity.

“Life on earth in the broadest sense depends on biodiversity and the ecosystems that biodiversity makes up.”

And it’s not like there’s just one issue driving the global – or national – biodiversity decline.

Habitat loss. Pollution. A changing climate. The exploitation of wildlife. Invasive species. All of these are massive problems, and each issue is connected to the others, making solutions even harder to come by.

As David tells us, “there’s no single answer, so I would say: be wary of simple solutions to these complex problems.”

Indeed, protecting biodiversity will be hard work and will require creativity. But David explains there is good news.

“People are more likely to take actions if they see other people also taking actions.”

There’s no shortage of ideas of how to take action to safeguard our biodiversity – how to save our species in decline. But guess what we are short on? Time and money.

And that was the case before COVID hit.

The pandemic? It’s not made the situation any better.

But we do know how much it will cost to save biodiversity globally.

The final bill? It could be as little as $125 billion dollars a year.

That might sound like a staggering amount, but it equates to roughly a third of what just our government spends in a given year. If every government in the world pooled their resources? Yes, we could afford the bill, even if the true cost is determined to be much, much higher.

However, not every government will help pay the bill. And then there is the question of whether some countries should pay more of that bill than others, given the out-sized role they’ve had in species decline. That question, even if fair, might cause a country to balk – it might raise the price beyond their means.

Look, it gets complicated fast.

And it gets even more complicated when you begin to realize that some countries – like Canada, because of our vast land mass – will need to do more than the average country to save biodiversity. That’s a hard sell.

Then there’s this:

Some species will be easier to save than other species, in part because the cost of saving each species will vary. Some will cost mere hundreds of thousands to recover, while other species will cost hundreds of millions.

Why?

Many reasons, but here’s a critical one to ponder: Some species are simply considered to be of special concern – grizzly bears, for example.

Many reasons, but here’s a critical one to ponder: Some species are simply considered to be of special concern – grizzly bears, for example.

What does that mean? Famed bear biologist Dr. Stephen Herrero explains.

“Certain populations are definitely vulnerable. And what we’ve seen in North America is a shrinkage of grizzly bear populations into more and more core habitat.”

But even though certain populations are endangered, Stephen says “grizzly bears as a whole in Canada are surviving and probably will do so for a few decades.”

In other words, grizzly bears in Canada won’t be going extinct tomorrow, but their future is far from secure. Yet because grizzlies aren’t on the brink, we have a real chance to protect them, Stephen tells us.

“Co-existing with bears by virtue of understanding their needs, spending the money that it takes to interface people’s needs and desires with grizzly bears is essential. Whether we continue to do that with more and more people where bears are? That remains to be seen.”

Whether we will spend the money – allocate precious financial resources – to save a species that isn’t on the brink is an open question, given that so many other species are in such dire shape. And maintaining grizzly bear populations is expensive work, as Stephen outlines.

“For example, in Banff National Park, look at all the underpasses and overpasses and the millions of dollars it has taken to build and maintain them. They’re there to decrease grizzly bear mortality, and also to provide a way for different portions of the population to keep genetically connected.”

“For example, in Banff National Park, look at all the underpasses and overpasses and the millions of dollars it has taken to build and maintain them. They’re there to decrease grizzly bear mortality, and also to provide a way for different portions of the population to keep genetically connected.”

But the cost to save grizzlies will only go up if we wait, Stephen continues.

“You don’t get any giveaways with a species like grizzly bears.”

Why? Stephen says, “they’re one of the more difficult species to maintain. If the population is under stress at all, because they have very large home ranges, it’s not easy to keep grizzly bear populations alive.”

In other words, Stephen thinks we need to take advantage of a good deal when it’s presented: We should act now to save grizzlies when the price tag is mere millions, saving us potentially hundreds of millions if we punt hard decisions down the road.

Moreover, as biologist Sarah Ramirez tells us, when we spend the resources to help grizzlies, we get incredible bang for our buck.

“When you look at a grizzly bear and you protect the habitat of that one grizzly bear, you’re actually protecting the habitat of all the other species that it comes into contact with too. You’re helping what it eats, what it preys on, what it defends from its territory – the wolves, the ravens – everything that it works in co-existence with.”

Think about it: As we save big, far ranging charismatic megafauna like the grizzly, we learn more lessons about how best to save species; we become more efficient at doing our job of conserving species; and we undoubtedly will be able to save some other species while trying to save, say, the grizzly bear.

That matters, according to former prime minister Kim Campbell. Not just because it saves us money, but because “what people also want is hope. (We need) things that people can be mobilized around, like species preservation.”

And yet there is less hope for other species that are closer to the brink of extinction.

The northern spotted owl? Fewer than 10 remain. The southern resident killer whale? There are fewer than 100 left in the world.

To save these species? It’s going to be very expensive.

You see, it’s a truism that the fewer animals remaining in a population – within a regional or global system – the more expensive it will be to recover that species.

But here’s the thing: It’s also a truism that cost won’t be going down; the longer we leave it, the more expensive the problem will become.

And the more expensive the problem? The less likely we are to actually spend the money to protect a species at risk.

Which begs the question: Why do we hesitate to act? Why do we leave species protection to the last minute?

Barbara Cartwright thinks she has the answer: “Because I think it is abstract to us until it happens to us.”

Barbara is the CEO of Humane Canada and she believes extinction is hard to comprehend. Consider the extinction of the western black rhinoceros, Barbara tells us.

“Everybody was writing on social media about how terrible it was that this last rhino had died, but people have been sounding the bells for decades that that was exactly what was going to happen and we just kept letting it happen. But then everybody – the average person – seems to get on board with this (grief). I’m not questioning that they were really feeling grief about it…but they never stood up to make it stop.”

“Everybody was writing on social media about how terrible it was that this last rhino had died, but people have been sounding the bells for decades that that was exactly what was going to happen and we just kept letting it happen. But then everybody – the average person – seems to get on board with this (grief). I’m not questioning that they were really feeling grief about it…but they never stood up to make it stop.”

Why did we do nothing?

“One of the things that I’ve seen happen that’s very interesting is that people will get very deeply moved by extinction. (Then) they start to get into it and they start to realize just how big the problem is and they literally shut down. They can’t seem to take in the enormity of the multiple ways that animals are suffering in our world and then they turn away”, Barbara says. “But then the one rhino dies and it’s sad. You know what I mean? It’s something they can hold on to without having to feel like they have to take on the entire world, which seems structured against animals.”

Barbara has spent most of her life trying to get people to care for animals – trying to stop extinction. And she believes we run the real risk of losing our most threatened species because “whether it’s extinction, whether it’s cruelty, we don’t stand up to make it stop. We don’t vote on this issue. People don’t go to the polls on it, so government doesn’t have to make it change.”

Barbara has spent most of her life trying to get people to care for animals – trying to stop extinction. And she believes we run the real risk of losing our most threatened species because “whether it’s extinction, whether it’s cruelty, we don’t stand up to make it stop. We don’t vote on this issue. People don’t go to the polls on it, so government doesn’t have to make it change.”

Barbara passionately believes we need to start caring for our species at risk – spending the resources to save them. But she adds “the enormity of the issues facing the environment – where we live, our world, our home – is monstrous. It’s so much easier to watch Netflix.”

It’s true. It’s easier to ignore the problem, so we do. And then it gets pricey and we balk at the price tag.

Discuss

But some believe that cost shouldn’t be part of the discussion, like biodiversity advocate Dr. Harvey Locke.

“This idea that too many resources (are being used)…all of that is nested in a scarcity mindset. There’s an unarticulated conversation going on there that resources are scarce, so my priorities should be first over your priorities.”

Harvey, who is advising governments globally on how best to conserve biodiversity, believes it’s not a question of whether we have the resources to save endangered species, but one of getting creative and actually acting.

“Underlying so many of these conversations is competition. What we have to do is shift that scarcity mindset into an abundance mindset. What do we need to do to maintain the values of everyone in this relationship?”

Gena Rotstein agrees.

“I don’t see the world in a lens of scarcity, I see it in a lens of abundance.”

Gena is a philanthropic innovator and organizer. She helps marshal resources to help causes that need support. And Gena believes if species need saving, we need to recognize the problem isn’t a resource issue.

“For me, that’s a systems issue. We have a problem with how we’ve crafted our wildlife protection system. And it’s built on a culture that was designed for coming in and taking over, as opposed to one of engaging and nurturing and bringing in.”

For Gena, the question we need to ask is: “How have we incentivized some of this?”

In other words, Gena believes what we say or don’t say, who we vote for or don’t vote for, what we spend money on and what we don’t buy all helps create our system. As a result, Gena says, “we as a society need to decide what we want our culture to look like. And it’s from that culture that we can choose what policies we want to adopt as a family, as a business, as a society and then look at how we want to resource it, how we want to build the infrastructure and the supports around it.”

Sam Sullivan agrees with Gena that we are the system.

“I often thought, what would it be like to give nature or wildlife a vote? What a different world we might live in. But that’s not what happens, so that means that humans have to speak and vote for those who can’t.”

Sam is a former BC cabinet minister and the former mayor of Vancouver. Few understand what drives decision-making better than him.

Sam explains that “everybody wants to have a healthy environment, but there are different opinions on how we (accomplish that).”

In other words, not everyone agrees that an abundance of resources is simply a mindset.

“The environment has been sometimes described as a ‘full stomach issue’. People have to have full stomachs before they start caring about the environment, and you can see that in many parts of the world where there’s more poverty or suffering. In these cases, people have very little interest in environmental policy,” Sam argues.

Pollster Shachi Kurl agrees, telling us “these decisions are very much rooted in a matrix that starts with your home economics: Can I afford my rent? Can I afford to feed my children? Am I worried about having a job next year? It’s a much tougher sell, so I would agree with Sam on that front.”

Which is why, to save our species at risk, Sam Sullivan believes “people have to feel that there is something in it for them; that they are benefiting – or not benefiting – just as much as everybody else.”

Which is easier said than done, as Shachi Kurl adds.

“If a consumer market, for example, made it very easy to take action on issues of understanding, respecting, preserving, enhancing nature – if those were easy decisions – then I think we’d be taking them.”

That’s why, Shachi believes, like it or not, deciding what we can save is about resources – at least for the majority of us.

“Even when they want to pick the right thing, it’s still a matter of their pocketbook, and that’s what always seems to win.”

Dr. Victoria Lukasik is a biologist and she’s investigated this very question: How and why and when we act to protect species at risk. She argues that so many of our decisions boil down to this: “Charismatic megafauna.”

Victoria tells us that big, large animals – like bears and wolves – “are the things that draw our attention and they can be the things that we fall in love with, or we hate.”

And, obviously, that’s a pretty arbitrary way to decide the fate of endangered species. But Victoria says if that’s the world we live in, maybe we should lean into it.

“I struggle with this myself, as well. And the cynical side of me kind of thinks: We can’t save them all, so why bother trying? Why don’t we be realistic and focus on which ones we can save – or which ones we’re willing to save – and just make sure we do that.”

Maybe you agree. Maybe you don’t. But as you may have guessed by now, saving a species isn’t as simple as writing a cheque.

“There are these huge battles about wildlife, but it’s not really about the animals at all. It ends up really being about politics and people’s different values and they turn it into left wing versus right wing,” Victoria argues. “I find it very frustrating when that’s what happens because we’re not talking about reality anymore; we’re not talking about the animals and trying to figure out how to live with them. We’re just using them as a pawn in some sort of political argument.”

And that reality makes taking action to save species at risk that much harder. After all, for some species, to save them, all that’s needed is an expensive captive breeding program and a place to re-release the animals into the wild.

That’s fine if we’re talking about, say, the Vancouver Island marmot. But if it’s a complicated predator – the eastern wolf, say – being released back onto the landscape? Victoria tells us that’s a much bigger challenge.

“Carnivores kill things. We are threatened by that because we’re worried about our safety, we’re worried about the safety of our livestock, our pets, our kids. Or we’re hunters and we’re competing with them – or that’s at least how we perceive it.”

And then there’s this: To recover most species – including highly endangered animals like the northern spotted owl, the southern resident killer whale and the mountain caribou – the cost is not only research and management or captive breeding and reintroduction. In most cases, species need habitat protected or revitalized or both. That means halting human development in large areas – and likely curbing recreational activities across the same ecosystem.

Victoria believes “our economic interests are things that are often in contrast with what is best for wildlife and our environment. It’s not to say that it has to be environment versus jobs. There are other ways, but that’s the way we operate as a society.”

In other words, saving what we fear losing isn’t just a line item in a budget. I mean, it’s that too, but it’s also possible jobs will be lost and cultures will be changed. Tax bases might be altered. Regional economic power might shift. National divisions might be exposed or deepened.

So, yes, we have the financial resources to save our species at risk. But do we have the political will – the public appetite – to have the hard conversations required and make the needed sacrifices? And even if the answer is yes for some species or some regions, across the totality of the system – the totality of our nation – will the answer always be yes?

If the answer is no, the question is this: Can we actually save every species?

“It’s so important that we bring controversial ideas into public discussion. People don’t want to have those discussions, but I think people should be aware of them and people should engage with them. That’s the way we get better government.”

– Sam Sullivan | Former Mayor of Vancouver

Task

What do you think?

Terms & Concepts

Referenced Resources

* Quotes have been edited for brevity and clarity.