The Context of it All

Chapter Two

To understand where we’re going, it’s helpful to know where we started.

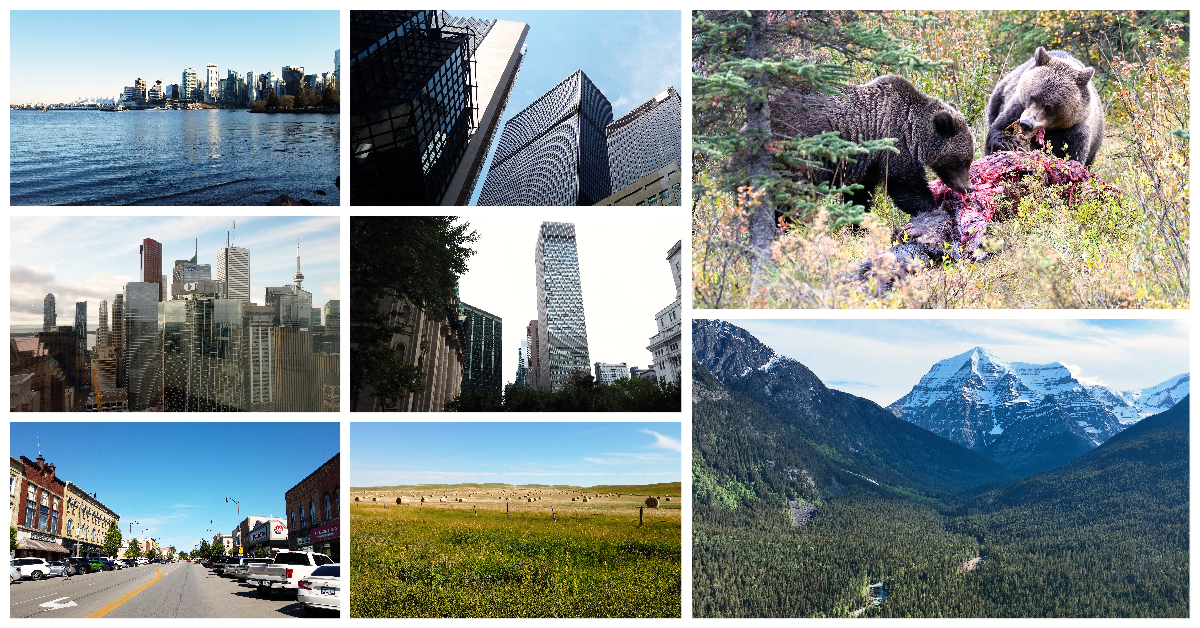

Just like in nature, there’s a unique context to every region in Canada – a landscape that often has determined how we make our living, shaping our economy, values and beliefs in the process. And it’s a context we need to understand if we’re to develop research that resonates with people from different walks of life – develop research that can articulate a true balance between the needs of people and nature.

Historically, Canadians have been known as hewers of wood and drawers of water. In other words, we’ve long been known as a resource economy. A trading nation. But that’s the sum of the whole, or has been since about the time we moved on from trading the fur of critters to focus on building a railway to unite the land.

Within each region, some are better at the water drawing stuff and some are better at being hewers of wood. And those particular skills – those slight differences? That’s what makes each region valuable to the whole. It’s also what makes some regions think a bit differently than the whole.

You see, drawing water – or, more specifically, fishing cod – was super valuable to the Maritimes. Until it wasn’t. Hewing wood – logging – and drawing water – fishing – was about all BC was good at. Until it wasn’t.

As Canada developed, like in nature, some areas had a head start on new economies – what our two bears would call new niches – because of population, proximity to power, proximity to markets or all of the above. Like Ontario!

Other provinces that didn’t have the advantages of population or power or access to markets had to be more industrious and, say, find oil in the boggy sands of the northwest boreal forest. Like Alberta!

How a province settled and developed – the resources they inherited, the jobs they created, the values they developed? That’s history, sure, but it’s also a window into the future. It’s the context needed to understand current political and economic debates – especially surrounding the environment.

How so?

Well, as an example, even though almost every Canadian likes nature and believes nature matters, few can agree on how to safeguard biodiversity.

Well, as an example, even though almost every Canadian likes nature and believes nature matters, few can agree on how to safeguard biodiversity.

The value or priority we place on the protection of nature usually varies based on the province we call home. In a region with a history and culture and economy that remains tied to the development of nature, support for conservation won’t be as high as in a province that has evolved differently.

And then there’s this: some provincial governments will be more antagonistic towards environmental regulations, like a carbon tax, but will be supportive of parks because environmental regulations, not parks, clash with the culture and economy of the region. Whereas, in other regions, the opposite will hold true.

Of course, regions aren’t just provinces, they’re also areas within a province too.

Take BC or Ontario. The majority of both provinces consistently tell pollsters they love parks, but the majority of the population in both provinces also live in and around their major urban centres. Outside the big cities? Well, there’s a different outlook.

Why? Because, as you now know, whether you’re a bear or a human, it’s hard making a living on this landscape. —->>

Why? Because, as you now know, whether you’re a bear or a human, it’s hard making a living on this landscape. —->>

And even if a specific landscape – say, Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario or Mount Robson Provincial Park in BC – is iconic, the history and culture of the region might value the land for more than its beauty.

Some regions have limited economic opportunity – forestry or mining might be the major employer or, in the case of some communities, the only employer. Access to land is imperative for development, obviously, but also to those who rely on the jobs created by development.

But, wait, you say. Canada has a lot of other land that can be developed. We can save the beautiful views and the rare animals and find other spaces for the loggers and miners.

Well, it’s true that Canada is vast, but consider that a forest can take decades or even centuries to regrow and be economically productive for logging once more. Between the demand for our resources, the limits placed on how much development can happen on any given parcel of land, and the fact that development is often not renewable within one generation, to sustain jobs and the products we demand, more and more land is needed for development.

Now factor in how many small communities exist within regions that depend on resource development and you begin to understand why the places we all can agree are special are still desired for development; why some famous parks, even, get opened to development.

There is a flip side.

In some regions, resources – like fish – have been overexploited and lost, meaning parks and conservation might actually offer economic lifelines for communities that would otherwise become ghost towns.

That context can help us understand why different provinces and different regions – or electoral ridings within a province – view the same issues differently.

That context can help us understand why different provinces and different regions – or electoral ridings within a province – view the same issues differently.

Make sense? Good! Now know this:

The historical context of a province – or region within a province – might also inform the culture of a region or a community.

Here’s why that matters:

It’s context that explains why some provinces focus on defending the rights of individuals, while others are focused on protecting population rights. It explains why some populations with a deep connection to settling land still want to overcome the challenges presented by nature, while others with a deep connection to the land want to protect nature from the challenges we create. And it also explains why some communities value parks for the recreational opportunities they protect and why some communities dislike parks for the recreational opportunities they prohibit.

And, look, this context might leave you thinking that urbanites and the eastern provinces value nature more than the prairie provinces and rural communities, but the former mayor of Vancouver and former BC cabinet minister Sam Sullivan says think again.

“There is a misunderstanding that many people from the rural areas don’t care as much about nature, but that’s not true at all. They’re the ones that actually enjoy it and are part of it. And it seems to be the urban people that are living in the least-friendly natural areas that are the ones that are in favour of nature.”

Danijela Puric-Mladenovic is both a professor and professional forester. And she agrees nature is threatened by urban development.

“When you look at the areas where most of our population lives, this is where our forests are not in the best of shape.”

Land-use advocate and Métis leader Brock Endean believes it’s for this reason why rural communities are often better stewards of nature.

“I find, up in the north, you have a lot more youth that are connected to the outdoors. They go hiking more; they’re out on the rivers more, out on the lakes. I think they have a lot more consideration for what’s happening in their local area and what that means on the grander scale. While down in an urban setting, sometimes that’s lost.”

Libby Garg, an entrepreneur and member of the Okanagan Nation, was born in a rural community and now lives in downtown Toronto. As she explains, “Living in a rural setting really does give you a broader perspective of where our food comes from.”

Libby Garg, an entrepreneur and member of the Okanagan Nation, was born in a rural community and now lives in downtown Toronto. As she explains, “Living in a rural setting really does give you a broader perspective of where our food comes from.”

Whereas environmental lawyer Kerrie Blaise – born in Toronto and now living in rural Ontario – tells us, “For those of us living in urban environments, we might not understand ecosystems like someone who lives in the prairies, or someone who lives in northern Ontario.”

There is, of course, a but, Kerrie adds.

“There’s a concept called ‘shifting baselines’ and shifting baselines is defined as being something that you’re born into. So, when you’re born, you see that as the natural world, and anything that changes in that natural baseline is somehow unnatural (even if it is natural). And, so, we have inherent biases. Our lived experiences can have that limit.”

Indeed, Robson Valley-based community builder Bruce Wilkinson says rural communities understand nature best because “if people don’t connect to the land, they don’t have a value for that land. They don’t understand where their life comes from.”

But Libby Garg counters that in rural regions, often, the value placed on nature is economic.

“In large part, rural communities are based off of the type of work that is tied very much to land.”

And that’s a problem, according to forester Danijela Puric-Mladenovic. She believes when jobs are on the line, we put even more faith in what our eyes tell us and the eye test doesn’t always tell us the full story.

“What you see above the ground, it’s kind of easy, but all of that biodiversity that is within the soil, the trees? It’s huge. So, we need to simply stop justifying (why biodiversity matters). We just simply need it to survive as a species.”

But forester and rural historian Art Carson counters that when we look at issues from a wider view – a national level, say – we create solutions that don’t account for upstream consequences; we don’t account enough for local realities. The consequence?

“Local populations have seen that as basically outsiders putting nature ahead of human beings.”

Entrepreneur Libby Garg argues that it’s for this reason we must learn from those with different perspectives – something that Libby says is often more easily accomplished in urban centres.

“Urban settings are often a melting pot of multiculturalism, different ideas, innovation. I’m going to stereotype here, people who live in a more rural setting, where the distance between individuals is often greater, don’t often have the same mixing of ideas and the same diversity (that urban centres enjoy).”

“Urban settings are often a melting pot of multiculturalism, different ideas, innovation. I’m going to stereotype here, people who live in a more rural setting, where the distance between individuals is often greater, don’t often have the same mixing of ideas and the same diversity (that urban centres enjoy).”

That means those living in urban settings might have a different, if equally valuable, view of our natural context because, in part, it’s informed by what a large, diverse population has taught each other. And, interestingly, that sharing of knowledge and skills is also what makes cities such economic powerhouses.

However, as economist Sean Mullin explains, the economic success of cities is creating a divide with rural communities.

“Particularly knowledge-based industries benefit from what’s called clustering – bringing together very talented individuals and companies and technological know-how and building, essentially, clusters of economic activity. Those clusters, because of their size, need cities. And what you potentially have is this movement, where economic opportunity is much more concentrated in the city, creating a hollowing-out effect in rural Canada.”

That’s one reason for what’s known as the urban-rural divide.

Though western and eastern Canada might have different contexts – though two western provinces might even have different contexts – the very different history, values, culture and economics of rural communities and urban centres? Shachi Kurl argues, “That is now framing and reframing almost every facet and part of Canadian policy and societal debate.”

Though western and eastern Canada might have different contexts – though two western provinces might even have different contexts – the very different history, values, culture and economics of rural communities and urban centres? Shachi Kurl argues, “That is now framing and reframing almost every facet and part of Canadian policy and societal debate.”

Shachi might be best known for one question asked during one political debate, but her real role in our landscape? Executive Director of the Angus Reid Institute.

“Polling is measurement. It’s sociology. It’s demography. You can’t really know what people are thinking and what they’re feeling unless you go out there and ask them.”

Love or hate them, pollsters help us understand the context of our world right now.

“The study of what is in the minds of people is so important because it establishes a baseline. If all of a sudden you have a majority of people who are skeptical about the reality of climate change, or the need to protect nature, what are you going to do about it? But you have to know that. It might be scary, but you actually need to know where your base-line is – if the objective is to move the baseline – so you can know that you have to move it and how far you have to move it.”

And right now, when it comes to balancing people and nature, we need to realize we don’t all share the same opinions.

“We are now kind of at the thorny, crash-prone intersection of ‘what are we going to do?’ and that’s causing a lot of people to pull apart. Because even if we lived in a world where there was no action required at the end of agreeing with something: ‘ok, yes! Let’s all agree that climate is changing and that’s bad’. What are we going to do about it? That’s where the difficulty comes in.”

Which might explain Art Caron’s frustration.

“There’s somewhat of a difference between what we do collectively, rather than what we say and think and write individually.”

National action not reflecting our individual views? Yeah, it’s something that frustrates a lot of us. But Shachi says, “We tend to move forward with any issue when it feels like a broad coalition or a big tent. And the shrinking of the of the tent, or the stratification of the tent? You see this with this debate.

“(Canadians) have largely pulled to their corners and there’s not a lot of movement. So, think of it as a boxing ring – the pro pipeline folks are in their corner, the advocacy folks, the protestors, the anti-pipeline folks are in their corner. They seem to have very little to talk about anymore. And when issues are layered in around social justice, around equality and the rest of it, well, whose equality? Whose social justice are we talking about? Because this really comes down to, in economic terms, a perception of winners and losers.”

And who wants to be a loser?

It’s why rural-based forester Art Carson says, “People do want to be heard and they want their voices to make a difference.”

It’s also why urban-based forester Danijela Puric-Mladenovic says, “I truly believe that nature is more resilient than we think, but we have to help it.”

Neither are wrong. But to bridge the perspectives of Toronto and Valemount – the perspectives of Art and Danijela? Pollster Shachi Kurl argues, “Ultimately, the only way that we’re going to get to a place where everyone is sort of buying into something, is if they all feel like whatever it is they’re hearing is acceptable or palatable to them. And, I think, in the era of social media, we have lost the ability to question respectfully without being accused of either being a terrible person or not being patriotic, or this or that.”

In other words, the change we envision is only possible when we help address the priorities of our neighbours. And that’s only possible when we take the time to understand how our historical, regional contexts inform our economy and our values – and how our economy and values inform our political debates.

If we don’t? We all lose, most especially our democracy.